On his first day in class at the University of Toronto, Jaivet Ealom felt completely overwhelmed by his environment.

He sat at the back of the room and tried to absorb all the noise, technology and people. Nobody had any inkling of the harrowing journey he’d taken to get there.

A member of the persecuted Rohingya minority, Ealom had fled Myanmar in 2013. Before arriving at U of T, he had travelled through six countries and three continents seeking asylum — surviving a near-drowning and multiple detentions along the way.

“I essentially gave up everything overnight — all the support I had,” he says. “I was a lone stranger in this vast land without any safety net to fall back on.”

In those early years in Canada, Ealom — who spoke at an alumni event on June 15 — was trying to fly under the radar. He was worried about being deported to Myanmar or sent back to a detention centre.

Stephen Watt, who works at U of T’s Rotman School of Management and volunteers his time doing refugee advocacy, met Ealom about six months after he arrived in Toronto. Watt remembers how reserved Ealom was in the beginning.

“He’s not somebody who enjoys attention,” Watt says.

But the pair became good friends and now work together to support refugees and asylum seekers. Ealom, who plans to graduate from U of T in the fall with a double major in economics and politics, co-founded the Rohingya Centre of Canada as well as a non-profit called Northern Lights Canada with Watt. He is a member of the Refugee Advisory Network of Canada and recently attended an annual forum for the UN Refugee Agency on resettlement.

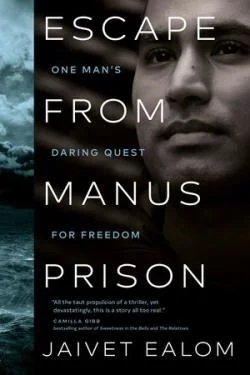

He also wrote his first book: Escape from Manus Prison: One Man’s Daring Quest for Freedom. Published by Penguin Random House Canada, it details his unimaginable story of trying to become a refugee in another country.

Ealom was first hesitant to revisit painful memories and share his story publicly. But he felt assured when he received his permanent residence status and wanted to be a voice for his friends who were still suffering in the detention centre

“He [shared his story] because he knew it’ll have a bigger impact beyond himself,” Watt says.

Even so, the process of writing the book was difficult, Ealom says.

“I woke up every single night — sweating — from a nightmare of being in a different prison. The more I thought [about my journey], the more memories resurfaced. It was retraumatizing.”

Growing up in a town northwest of Myanmar, Ealom says he developed an understanding about his life early on. “If you wanted to live, then you needed to leave,” he says. He fled first to Jakarta, Indonesia, but encountered an asylum process he describes as “barely functioning, chaotic” so he arranged to travel by boat to Australia.

“The crew was supposed to sail us to Darwin, Australia, where, according to a rumour that everyone had heard at one time or another, Australians opened their hearts and their country to people like us — those on the run for torture, persecution and death,” he writes in his book.

But the trip was perilous. On the third day, the rickety boat started to sink. For Ealom, who could not swim, death seemed imminent — until the refugees were saved thanks to a fisherman who spotted the boat.

After returning to Jakarta, Ealom set his sights next on Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean. This time, “I bought a truck tire and a pump in my backpack — a makeshift floatation device,” he says.

Ealom was mid-voyage when Australia, announced a change in the law: Asylum seekers arriving by boat without a visa would no longer be resettled in the country. Upon being intercepted by Australian authorities, he was handed a paper that stated he was an unlawful citizen.

“I thought, I didn’t do anything wrong, there must be some miscommunication.”

He spent 148 days in a detention centre on Christmas Island before being transferred to Manus Island, where he would spend the next three and a half years in a “living hell” that he says felt like a psychological experiment complete with rotten food filled with maggots or bits of gravel.

After studying every detail of the prison’s operation and securing the help of those around him, Ealom managed to escape. Posing as an interpreter, he travelled to Solomon Islands, where he altered his appearance and took on a new identity.

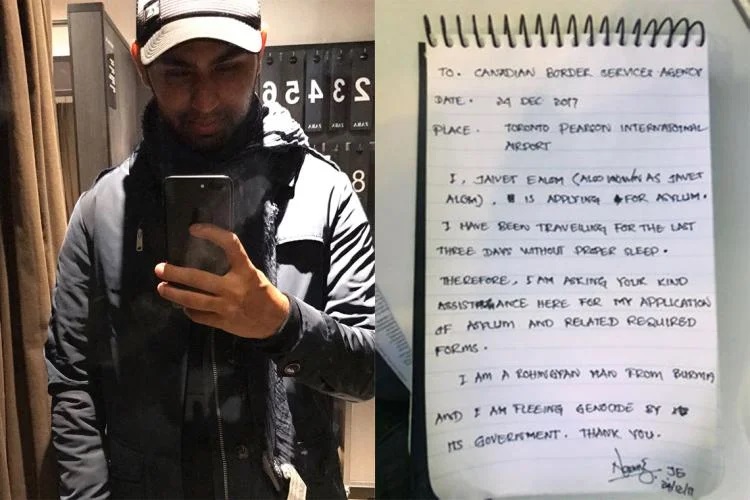

He ultimately arrived at Toronto Pearson Airport on a cold and snowy night on Christmas Eve in 2017.

“I didn’t know a single soul and I didn’t know the weather could get this cold,” he says. “I learned everything the hard way. But not in my wildest dream did I think I would live here.”

Fast forward to today and Ealom now calls Toronto his second home — even if it took him awhile to adjust.

For one thing, he says studying at U of T has been vastly different than any schooling he had done in Myanmar. “I wasn’t accustomed to challenging a professor,” he says. “I was taught that questioning anyone with slightly more authority than you is rude.

“There was no element of critical thinking. You can study philosophy [in Myanmar], but it’s watered down by the government. The textbooks are written by the military.”

His time in university has also helped him make sense of things that happened throughout his life. He learned that policy decisions that have enormous impact on people’s lives sometimes originate in academic research. “Without going to school, I wouldn’t be able to put a lot of things that I saw in a structured framework,” he says. “It helped me see the bigger picture. I was able to see some of the strategies driving the actions of the ruling regime in Myanmar.”

In his spare time, Ealom regularly volunteers with refugee organizations — and helped launch a couple himself. The Rohingya Centre of Canada, co-founded by Ealom and a friend, is a cause very close to his heart since it helps Rohingya newcomers connect with services and provide supports as they settle in a new home.

“When you come from an oppressed country, it’s easy to mistrust authorities,” he says. “That’s where we come in — we act as a bridge between the authority and the community.”

After graduation, Ealom is considering attending law school. He ultimately wants to return to Myanmar and make meaningful systematic changes — as long as his actions don’t put his parents in danger.

“I feel this moral obligation to help.”