“There are a lot of Italians in North American cinema, but North American cinema has not been kind to Italians historically.”

So says Alberto Zambenedetti, whose research focuses on Italian film as it relates to Italian masculinity, identity and diaspora.

When looking at the history of films about Italians, the negative stereotypes literally start with some of the first movies ever made.

One of the first is a silent movie called the Black Hand, made in 1906. “The Black Hand is a synonym for the Mafia,” says Zambenedetti, an assistant professor in the Department of Italian Studies and the Cinema Studies Institute in the Faculty of Arts & Science. “From the get-go, Italian immigrants are associated with crime.”

Another silent movie, The Italian, hit screens in 1915. It’s the story of an Italian gondolier who comes to America to make his fortune, but works as a shoe shiner and experiences tragedy while living with his wife and child in New York.

When you read between lines, you're seeing what it means to live in the diaspora, to lose the language, to have children who are no longer interested in carrying on what it means to be of a certain ethnicity.

“The Italian character is so animalized, he considers killing a child in the narrative. He doesn't do it, but he straddles the line between human and animal,” says Zambenedetti.

The 1931 film, Little Caesar, has legendary actor Edward G. Robinson play a violent Italian hitman who ascends the ranks of organized crime in Chicago. “Robinson plays a sinister uncontainable kind of criminal energy that's unleashed on society,” he says.

The first authentic portrayal of Italians in movies doesn’t take place until the 1950s with the 1955 film Marty. Ernest Borgnine, who is of Italian descent, played the lead role, and the film won the Academy Award for best picture.

Borgnine plays Marty Piletti, a lovable but socially awkward butcher who lives in the Bronx with his mother. “It has a lot of respect for the immigrant experience, which is something you hadn't seen before in Hollywood,” says Zambenedetti.

And then, in the late 1960s and 1970s, Italians had their own Hollywood invasion. “Directors of Italian descent started taking the reins and began to tell their own stories,” says Zambenedetti.

Martin Scorsese’s critically acclaimed films, Who’s that Knocking at My Door (1967) and Mean Streets (1973) were based on his personal experiences growing up in New York’s Little Italy.

“He would later make a documentary called Italianamerican where he talks about what it was like to grow up there,” says Zambenedetti.

And in 1972 Francis Ford Coppola took a gritty Mafia novel and created the iconic film, The Godfather, the movie to which all other Mafia pictures are compared.

While so many films about Italian Americans are about the Mafia, Zambenedetti urges viewers to look deeper — organized crime is just an effective vehicle to tell the immigration story.

“When you read between lines, you're seeing what it means to live in the diaspora, to lose the language, to have children who are no longer interested in carrying on what it means to be of a certain ethnicity,” says Zambenedetti.

Through the decades, Italians are frequently portrayed as working class — youth with few avenues for success. Take the first Rocky in 1976, that introduced audiences to Rocky Balboa, the uneducated, kind-hearted Italian-American boxer in the slums of Philadelphia who gets his shot at the heavyweight title.

Zambenedetti loves this movie because it really is art imitating life. “Its production matches the film’s content — with a young and unknown Sylvester Stallone getting a chance to make and star in the movie which is made for next to nothing,” he says.

Moving from the ring to the dance floor, Saturday Night Fever (1977) is forever remembered for John Travolta strutting to the music of the Bee Gees, and his slick dancing under a disco ball. It’s easy to forget he’s part of a struggling Italian-American family from Brooklyn where he works at a local paint store, earning $4 an hour.

“It’s often misunderstood,” says Zambenedetti. “It's actually a bitter, sad, somber film because it talks about a moment in American history where Italian youth didn't have anywhere to turn.”

The 1996 film Big Night starring Stanley Tucci and Tony Shalhoub captures the struggle between wanting to adapt the ways of the new world and preserving old traditions. They play two brothers who open an authentic Italian restaurant, competing with nearby Italian-American restaurants that serve far more westernized, and therefore popular cuisine.

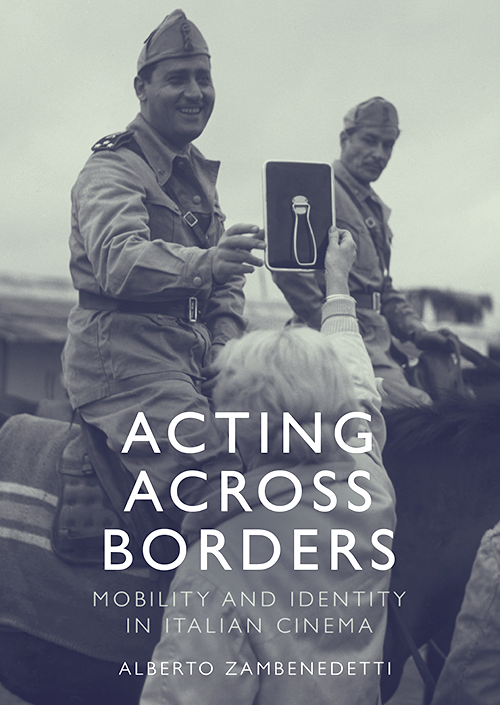

Zambenedetti’s interest in Italian film extends from Hollywood to Italy itself. In fact, he’s just finished a new book, Acting Across Borders: Mobility and Identity in Italian Cinema, that examines the concept of Italianità (Italian-ness) through the prism of Mobility studies.

I found it particularly apt to think about one of the most mobile peoples on earth, which are Italians. There's a huge Italian population in Toronto, of course, but Italians are everywhere. There's an enormous diaspora community in Brazil, the United States, Argentina, even in Asia.

His book follows the careers of two popular Italian actors, Amedeo Nazzari and Alberto Sordi, from the 1930s to 1980s. “I picked these two because they have been symbolic of Italian masculinity,” he says.

Nazzari came to fame in the 1930s during the age of fascist Italy and became an aspirational model for Italian men. the symbol of Italian men.

“He was tall with broad shoulders, the rock-solid stoic fascist man that goes against adversity and conquers it,” says Zambenedetti. “He does that often through command of a vehicle, he is often a pilot or a driver or a soldier on horseback — in command or control of something.

“Later on in his career in the post-war period, he’s a little older and becomes the quintessential father.”

Nazzarri stars in several films where he is pulled away from his family, forced to work overseas, and the picture is about his finding his way back to his country and family.

“It becomes a postwar narrative for bringing the nation back together through the figure of the nuclear family,” he says.

In the 1950s, Alberto Sordi hits the silver screen and becomes a different kind of national symbol. He’s not quite as masculine and stoic. Instead he is a little more comical and frustrated with life around him.

“He’s meek to the powerful and haughty to the meek taking advantage of situations, but always in a comedic way,” says Zambenedetti. “He aspires to have a number of romances, but they often end up badly for him.”

Sordi has enormous success as a comic actor and becomes the new image of Italian masculinity — far more human and relatable but also a bit insufferable, like a next-door neighbour you wish would move somewhere else.

Acting Across Borders also examines Italian cinema as it relates to mobility studies — an interdisciplinary field that explores the relationships between the combined movement of bodies, objects and ideas.

“I found it particularly apt to think about one of the most mobile peoples on earth, which are Italians,” says Zambenedetti. “There's a huge Italian population in Toronto, of course, but Italians are everywhere. There's an enormous diaspora community in Brazil, the United States, Argentina, even in Asia.

So it seemed to me, why don't we think about Italian cinema that way, what can that tell us about the way it identifies Italians both abroad and in Italy itself?”