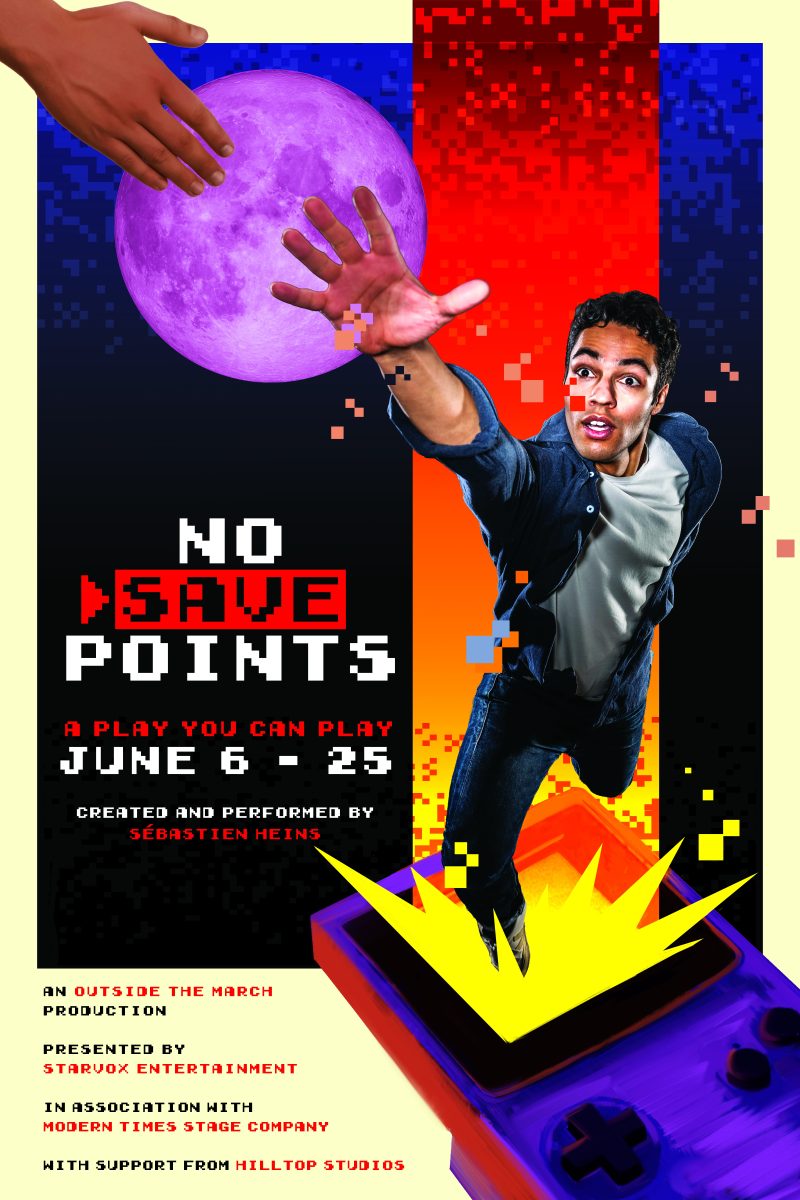

The BMO Lab for Creative Research in the Arts, Performance, Emerging Technologies and AI led by director David Rokeby at the Centre for Drama, Theatre & Performance Studies is providing its expertise to help facilitate an exciting new theatrical production called No Save Points created by actor Sébastien Heins and his company Outside the March. No Save Points will run from June 6 to 25 and is presented by Starvox Entertainment at Lighthouse ArtSpace.

Heins was one of the BMO Lab’s first artists in residence in 2020 - 21, a partnership between the BMO Lab and Canadian Stage, in which two artists were selected to immerse themselves in the lab’s technologies and experiment with ways to apply them to live performance. Rokeby and Heins also worked together on The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui by Bertolt Brecht, a co-production workshop between Canadian Stage and the BMO Lab in April 2022.

“It's really exciting as an artist to be able to link up with somebody with as much experience as David,” said Heins. “Often times technology seems like an impediment but interacting with somebody who is capable of turning technology into art inspires artists, people in our community, people in our industry, students, everybody to see technology as a fluid, very human tool.”

One of the technologies Rokeby and Heins dived into during the residency program, which is now playing a role in Heins’ production, is the use of a motion capture suit. This suit, also known as a motion shadow suit, shadows your motions and sends information to a computer from sensors at one hundred times per second; these sensors detect three-dimensional orientation and movement of the person wearing the suit. These data are then mapped onto a corresponding digital avatar or character that can be projected onto a screen.

The story in the play was inspired by the real-life events of Heins’ mother receiving the diagnosis of Huntington’s disease and his contemplation of the loss of control the illness can bring to one’s life, body and emotions. Heins found himself wanting to escape this brutal reality, which reminded him of his childhood when he would have to attend adult functions with his parents and want to get away. At these events, his mother would often let him escape through playing his Gameboy.

“I started to wonder how my love of theatre, my art form, my love and nostalgia for video games, and my love and respect and pride for my mother could intersect,” said Heins. “I found myself wanting to escape from the truth of that diagnosis, escape from how much control I was losing over my life and control my mother was losing over hers and so this Gameboy has become a symbol of taking back control.”

In this one-man show, Heins plays up to 10 different characters and uses the technologies of the motion shadow suit, a hacked Gameboy and a controller, to weave his way through a narrative that tells the true story of what happened to his family. The show entails a series of monologues interspersed with moments of psychological overwhelm when the character is compelled to escape into a game that represents the psychological processing of the character's real experiences.

“The use of technologies as a metaphor here is really key because it shifts it from being ‘okay here's a cool thing you can do', to ‘here is a way this character is working through things’,” said Rokeby. “The best uses of technology and art are when they are not just as spectacle, but there is a metaphorical relationship to the content in the story, so that the technology is adding to the texture of what the audience is thinking and experiencing, rather than just adding something cool.”

The audience has a key role in the show as well. The hacked Gameboy system allows an audience member to use a gaming controller to send signals to buzzers that are placed on Heins’ body through a haptic feedback system. Each buzzer tells Heins which direction to move in or if he should jump or duck in the video game world and simultaneously these motions are reflected in a digital avatar, the 10-year-old version of Heins. The entire scene is projected onto the show’s set, which will be a 15-foot-tall giant Gameboy.

The buzzer sensations are equivalent to what it would feel like to receive a text message on a cell phone in your pocket. Heins will be anticipating these signals on his body and will respond accordingly. Rokeby describes these moments like a sprinter in a race waiting for the starting pistol to go off. The physical demands in this show are incredibly high, but Heins explains that it is worth it because he sees this technology as leading towards a new level of theatrical Olympics and he’s inspired by the challenge.

When Heins escapes into the gaming world, there will be different scenarios that play out and each scenario has consequences. He will appear on a fantastical Caribbean island in the throes of the Black Death. He will have to navigate docks, sewers, laboratories, a plague prison and a “boss battle” and he will face dangers like pitfalls, fire, spikes and moving platforms. He will also get to meet his ancestors in the clouds, who give him special puzzle-solving powers.

As with any video game there is inevitably death. And just like in any video game, when your avatar dies, you can go back to the beginning and start over again.

“Having the mixture of a live performance in motion capture and this other world that the actor is also participating in creates this really interesting tension, which speaks to the fact that we now live so much of our lives at the precipice between the physical and the virtual,” said Rokeby. “That disjunction of the virtual and the real actor together, if played properly, speaks, I think, to a very contemporary experience.”

Rokeby describes how, in our current culture, we’re witnessing people trying to re-establish human connection in the face of advancing technologies. “We kind of know intuitively what we need, so as technology pushes us out of those zones, moves us further apart, or puts us on the opposite end of Zoom calls, we ask ourselves how can we get that thing we need within this new frame.”

The moments of interaction between Heins and the game controller operated by an audience member are peppered throughout the play but do not dominate the overarching narrative. Heins’ creative team is still working on ways to engage more audience members during those moments when only one member has the controller. They also still have to determine how that audience member will be selected to make sure they are comfortable with a controller.

Rehearsals will begin in May. During this time, Rokeby will attend a number of playtests when Heins and his team will test the game on players to improve the user experience and Rokeby will lend his skills and knowledge to work out any remaining kinks.

The BMO Lab and Outside the March would like to acknowledge the following collaborators who provided their support during the production’s development workshops: Mitchell Cushman, Nick Dobrijevic, Matthew Koscic, Aylwin Lo and Tori Morrison.

- To reserve tickets for the show, visit the No Save Points website.

- To learn more about the BMO Lab’s upcoming projects, visit the BMO Lab website.