The Great Lakes Research Alliance for the Study of Aboriginal Arts and Culture (GRASAC) recently launched a public platform that seeks to benefit Indigenous communities, cultural institutions and scholars alike.

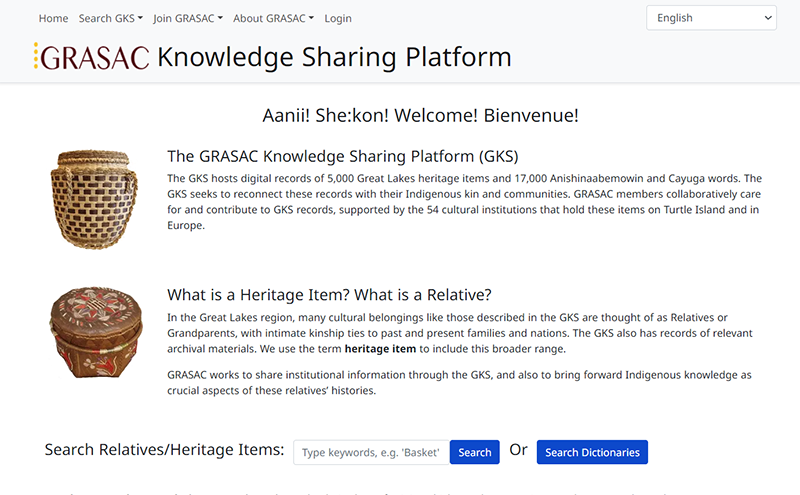

The GRASAC Knowledge Sharing Platform houses digital records of 5,000 Great Lakes heritage items and two online dictionaries with 17,000 Anishinaabemowin and Cayuga words.

The site catalogues a variety of artifacts including moccasins and headdresses; tools; blankets; hunting weapons; pipes; dolls; crafts; and historic photographs and artwork.

Every item in the platform has several image entries and a description outlining its function and how it was made. Also noted is its creation date, building materials, and its current location. Entries for some materials also include a searchable map that locates the heritage item’s place of origin.

“Every single item has story, has a journey,” says Heidi Bohaker, an associate professor with the Department of History and GRASAC co-director.

GRASAC is a multi-disciplinary research network with more than 500 members who jointly research Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and Huron-Wendat cultures of the Great Lakes region of Turtle Island.

The site was created through support from the Faculties of Arts & Science and Information and the Department of History.

Built on a previous password-protected platform designed mainly for scholars, the upgraded site answers the call from GRASAC Elders and Indigenous artists who encouraged GRASAC to make historical information more accessible.

“They said we needed to be thinking more about public audiences, in particular, Indigenous youth, artists and historians,” says Cara Krmpotich, an associate professor with the Faculty of Information and a GRASAC co-director.

The heritage items are primarily from museums and archives scattered across North America and Europe, with most artifacts dating back to the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Because of the British Empire’s history of colonialism and collecting, there are items that belong to Great Lakes Indigenous peoples in museums all over the world,” says Bohaker.

GRASAC and its partners, including a team of Arts & Science faculty members and students, have been compiling the site’s information for the past several years. “If one person worked nonstop and did one record an hour, it would take them 11 years to do all of them,” says Krmpotich.

Bohaker and Krmpotich didn’t want to list just basic information, they wanted to paint a picture of each item’s creation and use and make it meaningful for Indigenous users.

“We’re making sure we use language that is familiar and identifiable by those communities, not only the museums,” says Krmpotich. “We’ve really worked hard to prioritize the stories that connect these cultural belongings to the people and the lands they've come from.

“We asked, ‘How do we make sure that when people encounter their own history and heritage, their first reaction is not one of offense, but one of connection and belonging?’”

Krmpotich loves all of the heritage items but is especially fond of birch bark cases that were used for carrying cigars or other objects.

“These are really phenomenal,” she says. “They are embroidered with rich, intricate scenes done in quill that document clothing, animals, florals plants. You can see the shape of coats, the length of pipes, the kinds of hats people wore. They're so beautiful as historical documents and for their craftsmanship.”

The website’s two dictionaries offer a definition of each word, the Indigenous language it belongs to, and how it’s used in speech.

“Whatever we can do to keep parts of those languages alive and encourage them to flourish is important because language is how we carry knowledge,” says Bohaker.

“We’re actively working to improve linkages between heritage items and the dictionaries,” says Krmpotich.

Delighted that the site is now live, Bohaker and Krmpotich are quick to acknowledge the countless hours of work done by student research assistants.

“Students have done all kinds of things with us, they’ve done some of the photography, they've done data collection and they've traveled with us to site visits,” says Bohaker.

One student is Carlie Manners, a history PhD candidate who first joined the initiative in 2021. Since then, she has undertaken several research roles and is currently involved in the communications side of the project, overseeing a monthly newsletter and managing correspondence.

“My time with GRASAC has been invaluable in expanding my understanding of Indigenous Great Lakes cultures,” says Manners. “I've appreciated the opportunity to learn research processes and alternative perspectives on material culture informed by Indigenous ways of knowing.

“And I take pride in the public accessibility of the site. Traditional museum online databases are often colonial constructs, muting cultural subjectivities. The Knowledge Sharing Platform, however, allows for the inclusion of relevant information such as symbolism, interpretations, and the source of catalogue records.”

Both Bohaker and Krmpotich stress that this platform is far from finished — it will continue to expand. For example, plans are in the works to make the entire site available in French.

“It's always growing in content,” says Krmpotich. “It's also growing in terms of its target audience, and in the way that we've conceptualized how to share knowledge.”

But the impact of this site has already been tangible in the weeks since its launch, both from scholars and Indigenous communities.

“A museum in France reached out to us because they have records they want us to include,” says Krmpotich. “We have new artists contacting us. Within the first week of launching, we already saw signs that this site was doing what we hoped. That was super exciting.

“And if young Indigenous people come to this site, and if their encounter with this historical tool leaves them with a sense of pride, that's huge."

Says Bohaker, “We've built a lot of partnerships and shared a lot of knowledge. It's been quite a recuperative journey, and we still feel we’re at the beginning because there's still so much more out there.”