When Kate Holland was an undergraduate student, she had a “boring summer job” in a fishing museum cafe that offered one unexpected gift.

Because visitors to the small seaside museum in the United Kingdom were few that summer, it gave Holland the chance to dive into the novels of Russian literary icon Fyodor Dostoevsky.

“That was an intellectually galvanizing experience that has defined my career,” says Holland, an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Slavic Languages & Literatures, and president of the North American Dostoevsky Society.

This year is important for all Dostoevsky lovers, including Holland, as November 11 marks the 200th anniversary of his birth.

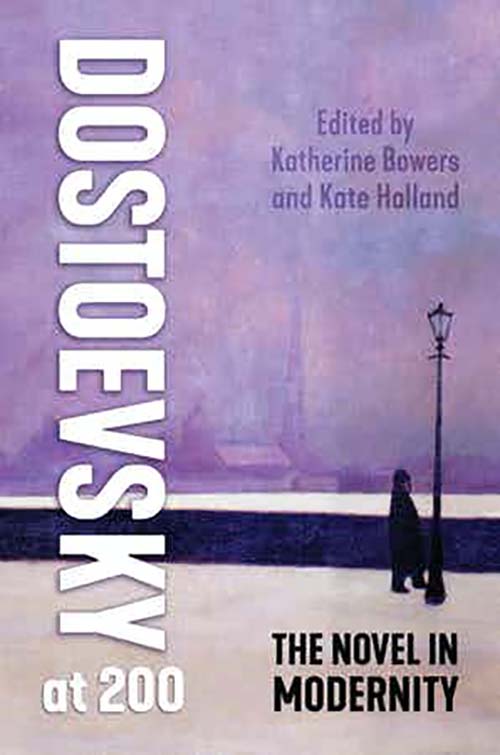

She has been celebrating much of the year and that includes the release of a new book, Dostoevsky at 200: The Novel in Modernity that she co-edited with Katherine Bowers, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia.

It’s a collection of ten scholarly essays written by international academics, including one by Holland. They examine how Dostoevsky’s novels explore the clashes between science, capitalism, materialism and technology with traditional cultural, religious and family values.

“I was particularly interested doing an edited volume, because that way, you can choose the scholars whose work most appeals,” says Holland. “It's mostly quite young, emerging scholars. We didn't want to go straight to the reigning monarchs of the field because there are a lot of exciting young scholars in Dostoevsky studies right now.”

Dostoevsky is one of the first 19th century Russian writers to struggle with what technology means. For example, his novel The Idiot opens on a train. What does it mean to go from traveling in a horse and carriage to traveling by train? The train is a metaphor for what happens to Russian cultural and social life in this period.

Holland’s essay is about the dying art of slapping people in the face as a response to being insulted or offended — a common Dostoevskian literary gesture — and its subsequent invitation to a duel. She examines how old forms and codes of behaviour in Dostoyevsky's universe, such as slapping and bowing, were breaking down amid an evolving culture.

Holland wanted the essay collection to focus on Dostoevsky as a writer of modernity because she’s intrigued with how he tackled big questions about the future in his novels. He is regarded as one of Europe’s first writers to raise concerns about science and technology, and how the world was rapidly changing amid shifting political, social and spiritual atmospheres.

“Dostoevsky is one of the first 19th century Russian writers to struggle with what technology means,” says Holland. “For example, his novel The Idiot opens on a train. What does it mean to go from traveling in a horse and carriage to traveling by train? The train is a metaphor for what happens to Russian cultural and social life in this period.”

He also questioned the validity of new and emerging areas of science such as statistics.

In Dostoevsky’s novels, there's always a lot of fear about the future. Who could have guessed we would all be communicating via technology and that it would be the only way we’re able to conduct a conversation with friends and family?

“There was a view about statistics that if you had enough data, you'd be able to explain everything,” says Holland. “Dostoevsky was very dubious about different types of claims that science was making.”

Holland found it ironic that much of the book was created over the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent example of the world suddenly changing, paired with an acceleration of technology.

“There's an appropriateness to it,” says Holland. “In Dostoevsky’s novels, there's always a lot of fear about the future. Who could have guessed we would all be communicating via technology and that it would be the only way we’re able to conduct a conversation with friends and family?”

In addition to the book’s launch this summer, Holland and Bowers have organized several online events such as a roundtable discussion of Dostoevsky at 200 on September 22 that attracted 80 students and scholars. It was part of a series of events to mark Dostoevsky’s bicentenary, co-hosted by the Department of Slavic Languages & Literatures and the North American Dostoevsky Society and supported by a SSHRC Connection Grant.

And for Dostoevsky’s big bash on November 11, a special online birthday party is planned. “We’ve put out a call for creative projects — performances, videos, stories, poems inspired by Dostoevsky’s works. Other talks, panels and roundtables will take place later this year and in early 2022.

“In a way Dostoevsky would be horrified,” says Holland of these digital celebrations. “One of his criticisms of modernity was that it was atomizing — everybody would be divided into individuals and that one of the problems of modernity is the breakdown of old senses of community.

“But at the same time, his ideas about modernity are double-edged. He also dreams that out of that brokenness, out of that atomization, something better might be able to be achieved.”

In other words, Holland believes he would applaud the creation of online communities meeting on Zoom from around the world to celebrate his work.

But with social distancing easing, Holland is overjoyed to be teaching her students in person again, as there’s no substitute for witnessing Dostoevsky’s profound impact.

“Dostoevsky was able to portray some of the questions teenagers have about themselves in the world,” says Holland.

“Students get into him so much. Some of his characters, like the protagonist from Notes from the Underground, is an extremely unappealing character. But he also gets under your skin in a way, especially if you're 19 or 20. Students will tell me they're so into his text.

“That’s why I feel it's an extraordinary privilege to study and to teach Dostoevsky, and to be able to have this connection with students.”