Marine protected areas (MPAs) found along coastlines and oceans worldwide are an increasingly popular strategy for protecting marine habitats and biodiversity. However, a new global study demonstrates that widespread lack of personnel and funds are preventing MPAs from reaching their full marine conservation potential.

MPAs are areas designated to protect marine species and habitats from local threats. Such areas include marine reserves, sanctuaries, parks, and no-take zones — fully protected areas that exclude any type of extraction — including fisheries, oil or gas — or any other development.

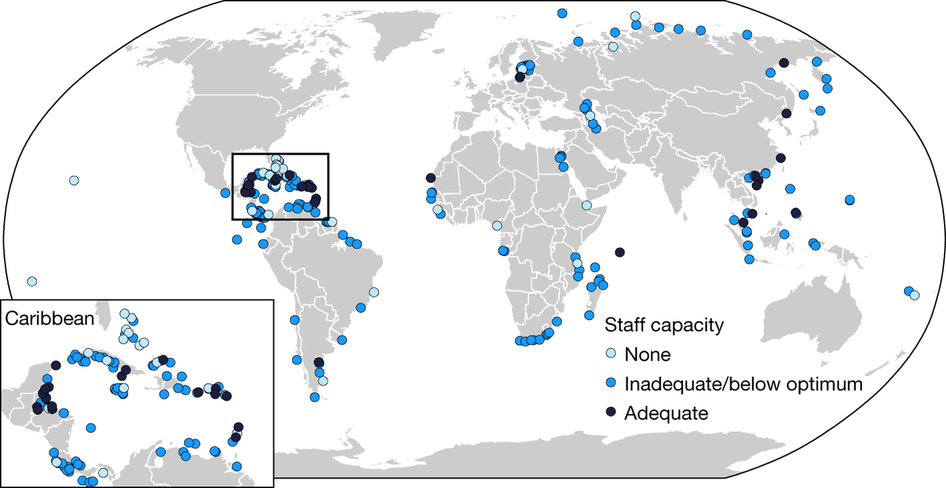

“From our survey of nearly 600 locations, we found only nine per cent of MPAs with available management data reported having adequate staff, and only 35 per cent reported acceptable funding levels,” said Emily Darling, a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and associate conservation scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), one of an international team of contributors to the study published in Nature last month.

“We were alarmed to learn just how few sites designated for protection report having sufficient human and financial resources to operate successfully. It highlights the need for further investment of practical resources for conservation,” said Darling.

Fish populations under greatest threat

After four years compiling and analyzing data on site management and fish populations in MPAs around the world, the researchers discovered that shortfalls in staffing and funding are hindering the recovery of MPA fish populations.

“Our study identified critical gaps in the effectiveness and equity of marine protected areas,” said lead author David Gill, who conducted the research during a postdoctoral fellowship supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) and the Luc Hoffmann Institute. “We set out to understand how well marine protected areas are performing and why some perform better than others. What we found was that while most marine protected areas increased fish populations, including MPAs that allow some fishing activity, these increases were far greater in MPAs with adequate staff and budget.”

While fish populations grew in 71 per cent of MPAs studied, the level of recovery of fish was strongly linked to the management of the sites. At MPAs with sufficient staffing, increases in fish populations were nearly three times greater than those without adequate personnel.

Such increases in fish populations as a result of greater investments could translate into further benefits for tourism ventures within an MPA, as well as for fishing operations beyond protected areas as populations spill over into open waters.

Reaching global targets

Marine protected areas are rapidly expanding in number and total area around the world. In 2011, 193 countries — including Canada — committed themselves to the Convention on Biological Diversity Aichi Targets, including a goal of “effectively and equitably” managing 10 per cent of their coastal and marine areas within MPAs and “other effective area-based conservation measures” by 2020. In the last two years alone, over 2.6 million square kilometers have been added to the portion of the global ocean covered by MPAs, bringing the total to over 14.9 million square kilometers.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the agency tasked with managing Canada’s MPAs nationally, estimates that 0.8 per cent of Canada’s waters are protected within MPAs, with less than 0.1 per cent being fully protected from fisheries extraction.

“We have a long way to go to meet international commitments towards protecting 10 per cent of Canada’s oceans, but there is exciting momentum building for this,” said Darling, a Canadian whose expertise is in collaborative big data for investigating the effects of climate change on coral reef ecosystems and the coastal livelihoods they support.

Expansion must be done properly and strategically

Darling and her colleagues on the study caution, however, that any increase in the numbers of MPAs by any country must be adequately supported in terms of staffing and operational funding, and must not come at the expense of existing sites.

The researchers propose a number of policy solutions — including increasing investments in MPA management, strengthening methods for monitoring and evaluation of MPAs, and prioritizing social science research on MPAs — in order to determine if they are meeting their social and ecological objectives by delivering the benefits they were designed to produce, and if they are being managed effectively and equitably.

Ultimately, the authors see an opportunity for individual nations to work together at a global level to protect a resource that is shared and used by societies worldwide.

“People around the world depend on marine resources that are managed fairly and effectively. With global collaborations, we can identify strategic future investments in marine protected areas, and track progress towards better social and ecological outcomes,” said Darling.

The findings are reported in the article “Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally” published March 22 in Nature. The research was supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from the National Science Foundation, as part of the Solving the Mystery of Marine Protected Area (MPA) Performance: Linking Governance, Conservation, Ecosystem Services and Human Well Being working group. Darling was supported by a David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship and the Cedar Tree Foundation prior to a Banting Fellowship.

With files from National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center and Nature