Emily Deibert didn’t pay a lot of attention to science before entering university, didn’t take physics in high school and began her undergraduate degree at U of T studying English.

“Then, I took Astronomy 101 as a science requirement and I thought it was fascinating,” she says. “My professors were Chris Matzner and Mike Reid and both were inspiring and great instructors and gave me a whole new perspective on science.

“But I didn’t know if it was even possible for someone like me who hadn't studied much science in high school to go on and pursue astronomy in university,” she says. “So I did some research, found out it was possible and made astronomy my second major.”

That interest grew throughout her undergraduate years and today Deibert is a PhD student in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics studying the atmospheres of exoplanets — planets orbiting stars other than the sun.

In recognition of her work, Deibert recently won an Arts & Science Doctoral Excellence Scholarship, an award given annually in recognition of academic excellence, quality of research and publications, as well as leadership and contributions beyond the University.

Her passion, initiative and leadership have made a significant positive impact in our department and our community. She was a co-founder of the undergraduate student's association in the department. Plus, she has been a strong advocate for student rights during her stint as co-president of the graduate astronomy students association.

“I'm honoured to have both my research contributions and extracurricular activities recognized by the Faculty of Arts & Science,” says Deibert. “I'm also really grateful to all of my mentors and collaborators who made this possible and who helped me get to where I am today.”

“Emily goes above and beyond the traditional expectations of a graduate student thanks to a strong research, teaching and service track record,” says Suresh Sivanandam, one of Deibert’s supervisors and a professor in the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics and the David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics.

“Her passion, initiative and leadership have made a significant positive impact in our department and our community,” says Sivanandam. “She was a co-founder of the undergraduate student's association in the department. Plus, she has been a strong advocate for student rights during her stint as co-president of the graduate astronomy students association.”

Deibert's other supervisor is Ray Jayawardhana, currently a professor of astronomy and Harold Tanner Dean of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University and a former professor of astronomy in the David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics at U of T.

Before the mid-90s, astronomers hadn’t observed a single planet beyond our solar system. But as observing techniques improved and instruments like the Kepler space telescope joined the hunt, discoveries came quickly and today, there are over 4,000 known exoplanets.

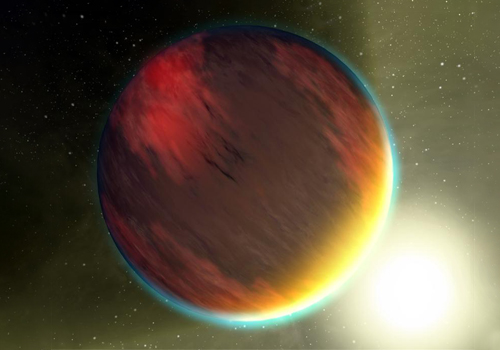

These distant worlds come in many sizes and vary widely in nature. Among them are “hot Jupiters” — gas giants that orbit close to their parent star and are much hotter than our solar system’s giants. And “super-Earths” — planets with rocky surfaces like ours but which are much larger.

Because they’re so distant and are outshone by their parent stars by a factor of a million, even the nearest exoplanets are extremely difficult to detect, much less study in detail. Deibert explores their atmospheres by observing the star’s light as the exoplanet passes between us and the star. As a star’s light passes through an exoplanet’s atmosphere, it picks up telltale clues about the composition of the atmosphere — clues astronomers can read.

Arts & Science News spoke to Deibert recently about the scholarship, her research and her science writing.

What do you think are the most interesting aspects of your research?

The most exciting part of my work is in trying to push the methods we use to detect and study these atmospheres because we're still in the early stages of this type of work.

I also think studying super-Earths is fascinating because they're so totally different from anything in our own solar system. Plus, we really don't know much about them because it's relatively easy to observe really large giant planets but if an exoplanet is closer in size to the Earth, it’s much more difficult.

For a while now, I've been looking for an atmosphere around a super-Earth called 55 Cancri e and my research is showing that it might not have an atmosphere at all. This is pretty interesting because it's obviously very different from the Earth and different from a lot of the planets in our solar system.

To many, the main question about exoplanets is whether there’s another Earth out there with life on it. Is this one of the reasons why you’re interested in this field?

For sure. And that's one reason why I'm really interested in Earth-like planets, even though they're harder to study. They're a first step toward learning if there’s life in the universe since it’s on these types of worlds where we’re likely to find life. It's especially exciting because of the potential discovery in Venus’ atmosphere of phosphine which may be a sign of life. In fact, even though I primarily study exoplanets, I'm starting to look at solar system research too. Whether there’s life on other planets is probably not a question we’ll answer soon but, yes, it's a question that’s always at the back of my mind.

In addition to doing research, you are a science writer. How did that part of your career develop?

When I was an undergrad I was doing a lot of writing but none of it was really science related. But when I started grad school, I started to think, okay, I'd like to continue to write but I’d really like to relate it to my research.

Plus, the Astronomy 101 course I took was what got me into astronomy in the first place. So I felt I owed a lot to good science outreach and good science communication. And another astronomy professor, John Percy, suggested I look into writing for the Varsity. So I reached out to them and said, hey, I'm a grad student in astronomy and I'd like to contribute. And so I wrote for them for a couple of years. It was a really great experience.

And now, I’m writing for research2reality, contributing a piece every two weeks. Plus, I’m trying to broaden my science-writing horizons, too, so I’ve written for a couple of different outlets on a freelance basis.

When you look back on your time at U of T, what do you think will stand out?

One of the things that was valuable to me while at U of T was the opportunity to do interdisciplinary work. If I had been at another university, I might not have been able to switch gears and pursue astronomy along with English. That's a really great feature of the undergrad program here — that you can study a subject like English at the same time as astronomy or whatever you want to study.

Also, in the astronomy department, there are so many opportunities for outreach, giving talks to school groups, travel to conferences. I feel lucky to be in a department that gave me all those opportunities and, even at the undergraduate level, to do so much research and learn so much.