As a cosmologist, Adam Hincks studies the universe as a whole.

In particular, he researches the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) — light from when our universe was only a few hundred thousand years old. In this primordial radiation, Hincks looks for clues to the origin of the cosmos.

Hincks also explores the universe as a Catholic priest belonging to the Jesuit order, studying different questions about creation from the perspective of his faith.

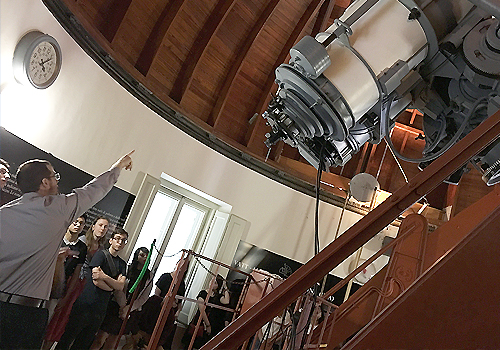

In 2020, Hincks joined U of T as an assistant professor cross-appointed to the David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics and St. Michael’s College. At St. Michael’s, he is the inaugural holder of the Sutton Family Chair in Science, Christianity and Cultures — a position jointly supported by the Faculty of Arts & Science and an endowment to St. Michael’s from alumni Dr. Marilyn Sutton and Thomas Sutton.

Hincks received his undergraduate degree in astronomy at U of T, after which he went to Princeton University for his graduate studies.

“I’ve always been a person of faith,” says Hincks, “and it was while I was in graduate school that the idea first came to me in a serious way of pursuing a religious life.

“By the time I was near the end of my graduate studies, it was pretty clear to me that this was what I wanted. So, after finishing my PhD, I immediately entered the Jesuit novitiate in Montreal.”

From there, Hincks’ scientific, philosophical and theological career paths have proceeded in tandem.

He received a diploma in philosophical studies from Regis College, Toronto School of Theology. That was followed by a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at the University of British Columbia. Then, a bachelor of sacred theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome; and most recently a master of theology and licentiate in sacred theology at Regis College. He was ordained in 2019.

“I’m in my late thirties,” he says with a smile, “and I’ve been a student most of my life.”

Arts & Science News spoke with Hincks about his unique perspective on the cosmos and the relationship between his scientific pursuit and faith.

Some people might think that the worldviews of a scientist and a priest would be incompatible. Why isn’t it for you?

Personally, I’ve never experienced that conflict and I think if you look at the two-thousand-year history of the Catholic Church, you don’t see it much. Many of the roots of the notion that there is a conflict are from the nineteenth century, which is quite recent, relatively speaking. In fact, throughout the history of the Catholic Church, there’ve been many priests who’ve participated in the inquiry into the natural world. For example, it was a Catholic priest, Georges Lemaître, who first came up with the idea of the Big Bang.

The Jesuit order has a tradition of a close relationship with science, doesn’t it?

Yes, the Jesuits have a rich history of contributing to science. You can see that connection in the 30-plus craters on the moon named after Jesuit scientists including Christopher Clavius who helped reform the calendar and Angelo Secchi who is often called the father of astrophysics.

Within the Jesuit order there’s a phrase that’s very central to our spirituality: finding God in all things. That can mean finding God in literature, through social justice, through the physical sciences, and so on. We look for God in all things and that view lends itself to science.

How did your scientific interest in cosmology and the Big Bang begin?

I was in the astrophysics and physics specialist program here at U of T, taking a number of astronomy, physics and math courses. The cosmology courses in particular piqued my interest. I also did a summer of research with Barth Netterfield and fell in love with not just the science but also doing research — programming computers for the BLAST telescope that observed galaxies in infrared light while hanging from a balloon, 40 kilometres above the Antarctic.

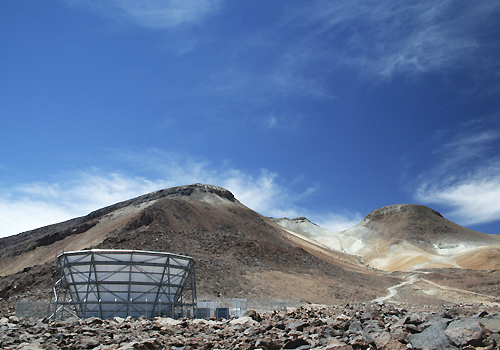

One of your main research collaborations right now is the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT). Can you describe what that is?

U of T astronomers have been involved in ACT for a long time. It’s a telescope in northern Chile designed to observe the CMB. In the past, I wrote a lot of the software that runs the observatory and I worked at understanding the raw data at a low level. The CMB is very faint, so you need to work really hard to make sure that you understand what in the data comes from the early universe and what is noise. ACT is also very good at discovering clusters of galaxies — groups of typically a few dozen galaxies — which are the largest gravitationally-bound objects. So now I’m involved in studies of these objects that can tell you about the evolution of the universe and how structure has grown.

Another project you’re involved in is the Simons Observatory. What’s that?

The Simons Observatory (SO) is a next-generation CMB facility that will be at the same site as ACT. In fact, the collaboration mainly consists of ACT team members joining forces with those who work on the nearby Simons Array. We’re building some new telescopes and one of our main goals is to look for a very tiny but very distinctive signal in the CMB called B-modes.

The leading theory for the early universe says that in the very first fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent extremely rapid expansion known as inflation. During this inflationary period, gravitational waves were generated which left faint B-mode signals in the CMB.

So if you detect B-modes, you’re building evidence for inflation and ruling out competing theories of the early universe. If you don't detect them, then it could be that inflation still happened but the gravitational waves were just weaker than your detection threshold. Or, it could be that there wasn't inflation. In any case, we’ll learn something fundamental about the universe. And we’ll be able to do a whole lot of other exciting things, such as probe the mass of neutrinos and study dark matter and dark energy.

In addition to your research, what courses are you currently teaching?

I'm teaching a course called Faith and Physics as part of the Christianity and Culture program at St. Mike’s — and I’m really enjoying it. We started by looking at ‘What is physics?’ and ‘What is faith?’ Now we’re looking at how they relate to each other. About half of the students are STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) students and the other half are from the humanities. So there’s a real mix of viewpoints and the discussions are very interesting.

For example, we looked at what it means to do physics. What is the scientific method? Which then led to questions of epistemology. The question came up in class: Could artificial intelligence do physics? And that sparked a lively discussion because some people knew a lot about computer science and other people knew about the philosophy of epistemology and they were able to have a rewarding conversation about that.

You are the inaugural holder of the Sutton Family Chair. What has that meant for you?

The chair came about because both St. Michael’s College and the Suttons wanted to enable a serious conversation about science, faith and culture. And that was something the University was interested in too. So the position lets me do my scientific research and explore that conversation.

As part of that mission, I proposed a new course that was recently approved by the Faculty, which will be jointly offered by both the department of astronomy and St. Michael's College. The title is The Bible and the Big Bang and we'll be looking at the question of creation from the scientific and religious points of view.

That's the sort of endeavor that was envisaged for this chair. And the chair is why I applied to U of T.