From eyeglasses to banks to newspapers to pizza, Italian ingenuity has changed our world in countless ways.

Italy is also where the modern academic study of crime originated in the 18th and 19th centuries, making it the perfect place for a U of T Summer Abroad course in criminology. That’s why, over the past decade, a select group of students has been gathering in the country each summer to earn a full year credit while studying key issues in the field.

This year, the Centre for Criminology & Sociolegal Studies' course Current Issues in International Criminology was taught by Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, an associate professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto Mississauga. A senior fellow at Massey College, his work examines the intersections of race, crime and criminal justice.

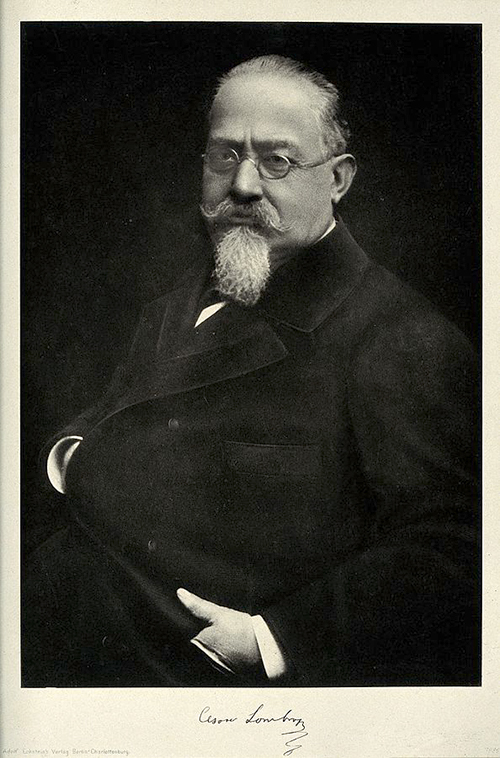

In Italy, he says, “Students learn about two key thinkers in the field who laid the foundation for criminological research — Cesare Beccaria and Cesare Lombroso. To study their work in the place where they conducted it is really quite novel.”

Subjects covered in the four-week course range widely: they include drug trafficking, organized crime and the Mafia, corporate crime, terrorism, street gangs and international policing.

“What I found most interesting was the really comprehensive overview of so many topics,” says Selia Sanchez, a fourth-year member of New College who is pursuing a double major in political science and international relations. “I’m not a criminology student, so it was a great opportunity for me to learn about a lot of things I don’t usually study.” Her experience inspired her to enrol in an international law course this semester.

Students visited a number of the cities for which Italy is famous, such as Rome, Florence, the Vatican and Siena; notable sights included the Colosseum, the Uffizzi Gallery and the wineries of Tuscany.

Such visits are familiar to many tourists. What set this trip apart, however, was Owusu-Bempah’s integration of course content with the field visits.

One example cited by Jacob Vaillancourt was a lecture about prohibition, held while the group toured wine country. “Though most people who use intoxicating substances do not commit crimes, Professor Owusu-Bempah cited the statistic that in Canada, 80 per cent of federal offenders have past or current substance abuse issues,” says Vaillancourt, a fourth-year member of Innis College majoring in criminology and sociolegal studies.

“And still, if we look back at the prohibition era, we see that it drove drinking underground and made it more dangerous. Over the course of the trip, we also saw how cultural attitudes toward alcohol are different in Italy than they are in Canada.”

“I certainly felt there was a need to incorporate key themes into the field trips,” Owusu-Bempah confirms. “On our first night in Rome, for example, we went on the ‘Dark Tour of Rome,’ in which a tour guide took us around and showed us sites where various atrocities had taken place.” Such sites had a historical focus, including the place where Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE.

The trip to Siena was notable in several respects; Sanchez particularly appreciated a police station visit.

“We got to see first-hand how a lot of policing is done, and we had the opportunity to ask the police chief questions. We also walked through the immigration office, saw a forensics office, and a couple of students had their mug shots taken. It tied in so well with what we were learning,” she says.

Another highlight was the Palio di Siena. This annual horse race dates back to the 17th century, and sees representatives from the city’s contrade, or city wards, competing against each other. “It’s incredibly competitive — when it’s finished you have to stay out of people’s way, because emotions are running high,” says Vaillancourt.

The students gained a central understanding of how cultural perceptions of what constitutes crime differ widely from country to country. At the same time, says Owusu-Bempah, countries now have to cooperate more and more on matters of mutual importance to all nations. That’s why it’s important to study crime in a global context.

“We can’t understand what’s happening here in Canada without a global perspective,” he says. “Globalization has contributed to the movement of people and to the rapid integration of information technology that facilitates organized crime and cybercrime. And when we think about the movement of jobs and resources — and what that has done for people’s economic outlooks — we can understand how these things influence crime as well.”

Yet while crime is a decidedly negative topic, Owusu-Bempah says that the course also offered very positive lessons about how public safety can be fostered. He points out that Siena’s neighbourly contrada system contributes more than just horse-racing teams: it’s an example of how citizens watch out for each other.

“Siena is a fairly small city, but it’s one with a very low crime rate,” he says. “In class we discussed the ways public safety is engendered: how we create safe communities and neighbourhoods. The more tightly-knit your neighbourhood is and the more connected people are, the greater the level of informal social control, and the lower the level of crime.”