Ramabai Espinet has spent years championing Caribbean women writers, a group too often overlooked in literary studies.

Now she teaches Caribbean Women Writers — a third-year course at the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Centre for Caribbean Studies that she has taught since 1999, offering her students the opportunity to explore the diverse and dynamic voices that have shaped this vibrant literary tradition.

She also teaches a course titled Caribbean Women Thinkers, focusing on a wide variety of non-fiction produced by Caribbean artists, scholars and thinkers. These two courses run in alternate years.

“I’m drawn to the ways Caribbean women writers address complex issues of identity, diaspora, resistance and cultural heritage, especially as these themes reflect broader geopolitical and social histories,” says Ella Davis, a third-year sociology student, with a double minor in African and Caribbean studies, and a member of University College. “The texts have also opened up discussions on motherhood and the expectations placed on young Caribbean women.”

Espinet, an award-winning poet, novelist, essayist and critic from Trinidad and Tobago, brings a distinct perspective to the course.

“Ramabai brings an authentic and nuanced perspective to our readings,” says Davis. “Her insights into the cultural and literary context of these works have enriched my understanding of the themes and voices within Caribbean women’s literature.”

Espinet remembers wanting to explore the work of women writers of the Caribbean herself when she was a student in the 1970s.

“Amazingly, the supervisor I talked to about it said, ‘Are there any?’” she says. “Of course there were. I did my PhD dissertation on two early Caribbean women writers: Jean Rhys and Phyllis Allfrey.”

Fast forward to today and Espinet reveled in choosing writers to examine for her course, making selections from a rich body of study-worthy work. “There's a flood of Caribbean women writers right now of different ages in the Caribbean and its multiple diasporas,” she says.

I’ve gained a richer understanding of the distinct narrative styles and voices that characterize Caribbean women’s literature, and of the vital role these works play in shaping cultural and political discourse.

For example, the class discussed the work of Jamaica Kincaid, an Antiguan-American novelist and essayist. Born in St. John's, the capital of Antigua and Barbuda, she now lives in United States and is a professor emerita of African and African American Studies in Residence at Harvard University.

Her 1985 novel, Annie John, chronicles the growth of a young girl in Antigua, delving into issues such as mother-daughter relationships, same-sex attraction, racism, depression, poverty, education, and the struggle between healthcare based on scientific fact versus native superstitions.

“It's a wonderful text in terms of how a young woman navigates the process of coming to adulthood, but within the specific context of Antigua in the late colonial period,” says Espinet.

“Annie John gave me further insight into the mother-daughter relationship as a powerful site of both love and tension,” adds Davis.

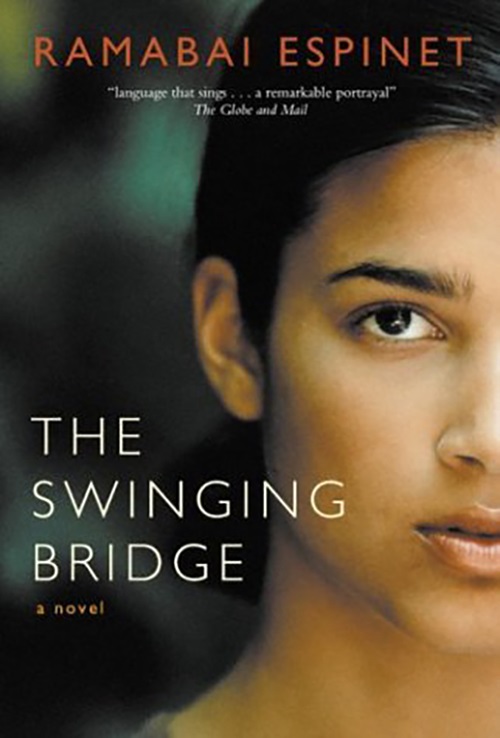

The class also enjoyed studying Espinet’s book, The Swinging Bridge which focuses on a multi-generational Indo-Trinidadian family living in Canada.

The book’s main character, Mona, who lives in Montreal, is asked to return to Trinidad by her brother, who is in the last stages of dying from AIDS, to reclaim property that their family left behind. As she returns to the Caribbean to confront her family's troubled past, readers step back in time to 19th-century India, and then to Trinidad, where her ancestors lived as indentured workers in sugar cane fields, eventually settling in North America.

“Getting to read Ramabai’s work, which offers a Trinidadian perspective, was definitely one of the highlights of this course,” says Emily Ramnauth, a fifth-year biology major with minors in immunology and women and gender studies, and a member of University College.

The course also gave Ramnauth new perspectives on her own history.

“As an Indo-Guyanese woman, this gave me a chance to read about women whose experiences resonate with my own, and those of women in my life,” she says.

This is my first Caribbean-focused class. I now have a deeper understanding of Caribbean women writers and how their work connects to my own ethnicity.

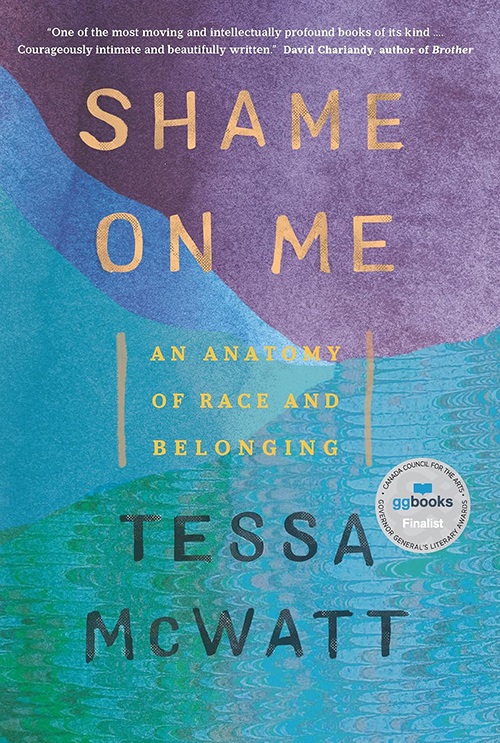

Tessa McWatt’s Shame on Me, a 2019 non-fiction book that explores concepts of race through the author’s multiracial identity as a Guyanese-born Canadian, was especially meaningful.

“She uses her family photos, Guyanese history and personal anecdotes throughout the book which was reminiscent of experiences I had growing up,” says Ramnauth. “One phrase in her book that validated everything for me is ‘race is a story.’ These words made what I felt over the years into something physical and real. This novel taught me my experiences are not so uncommon.”

Other texts of note in the course are The Dew Breaker by Edwidge Danticat, a novel on modern Haiti and the Haitian diaspora in New York, and How to Say Babylon, a memoir by Safiya Sinclair about the author’s formative years in rural Jamaica within the world of a Rastafarian family.

“The Caribbean is unlike any other place,” says Espinet. “One of the reasons for that is its incredible diversity which is often not appreciated because it's seen primarily as an area of Black settlement without understanding the complexity of its cosmopolitan character. But the Caribbean is the first modern migrant culture in the world, beginning with the arrival of Columbus in 1492.

“However, its peoples did not migrate there voluntarily; there was enslavement of African people. There was indentureship, following the abolition of slavery. Indentures were drawn mostly from India, but were also brought from China, Portugal and the Levant. It’s such a diverse region and you may not witness the diversity if you go there as a tourist. But if you live there, you experience so many currents crossing and influencing each other — in language, cuisine and culture. That’s why the music, art and writing that comes out of the Caribbean is so interesting and unique.”

Espinet is hoping this course gives her students a deeper understanding of the context, the culture, the literature and the incredible diversity of the Caribbean.

For Davis, Ramnauth and the other students, that understanding has already flourished.

“I’ve gained a richer understanding of the distinct narrative styles and voices that characterize Caribbean women’s literature, and of the vital role these works play in shaping cultural and political discourse,” says Davis.

Adds Ramnauth, “This is my first Caribbean-focused class. I now have a deeper understanding of Caribbean women writers and how their work connects to my own ethnicity.”