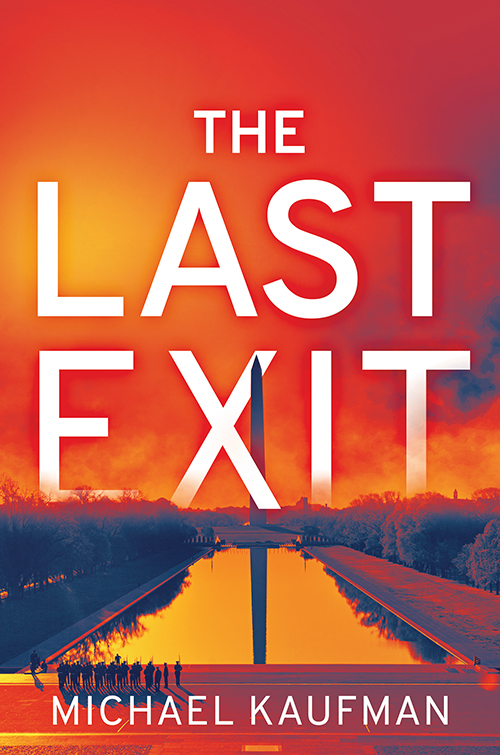

When Michael Kaufman finished writing The Last Exit in 2019, he didn’t expect to see uncanny resemblances between his fiction and reality mere months later — from a rapidly spreading virus and devastating forest fires to an uprising against police brutality and racism.

“It’s all there,” says the Faculty of Arts & Science alumnus, who studied political science and earned three degrees from U of T: a bachelor of arts in 1973 as a member of New College, a master’s in 1974 and a doctorate in 1984.

Set in Washington, D.C. in 2033, The Last Exit opens on a smoky day — the result of a massive forest fire on Shenandoah Mountain. The protagonist Jen Lu puts on an N95 mask.

“In the original manuscript, it said, ‘Jen pulled her N95 back on,’” says Kaufman. “As I was editing it, I thought, ‘No one’s going to know what an N95 is.’ How things have changed.”

Though the novel grapples with social and political concerns — including racism, climate change and economic inequality — they’re not the central focus of the novel, Kaufman says. His goal was to craft a compelling story that would attract fans of mystery, science fiction and novels in general.

“I wanted to write something that was a lot of fun to read but that also dealt with some really serious issues,” he says. “The protagonist is a female detective, a woman of colour, who faces various challenges because of both of those things.

“Of course, I’m not tossing words like ‘intersectionality’ into the mystery. These are the realities of her life, and yes, our lives are intersectional. But as it’s a work of fiction, I’m painting pictures rather than using the terminology I use in my academic, political or advocacy work.”

When it comes to all of the above, Kaufman’s resume is extensive. He has spent nearly four decades as an advisor, activist and educator to engage men in the promotion of gender equality. His work with the United Nations, governments, non-governmental organizations, corporations, trade unions and universities has taken him to 50 countries. In 1991, he co-founded the White Ribbon Campaign, the world’s largest movement of men working to end violence against women.

His articles have been translated into 14 languages in newspapers and journals around the world. He is the author of seven non-fiction books on gender issues, democracy and development studies. His most recent non-fiction book was The Time Has Come: Why Men Must Join the Gender Equality Revolution.

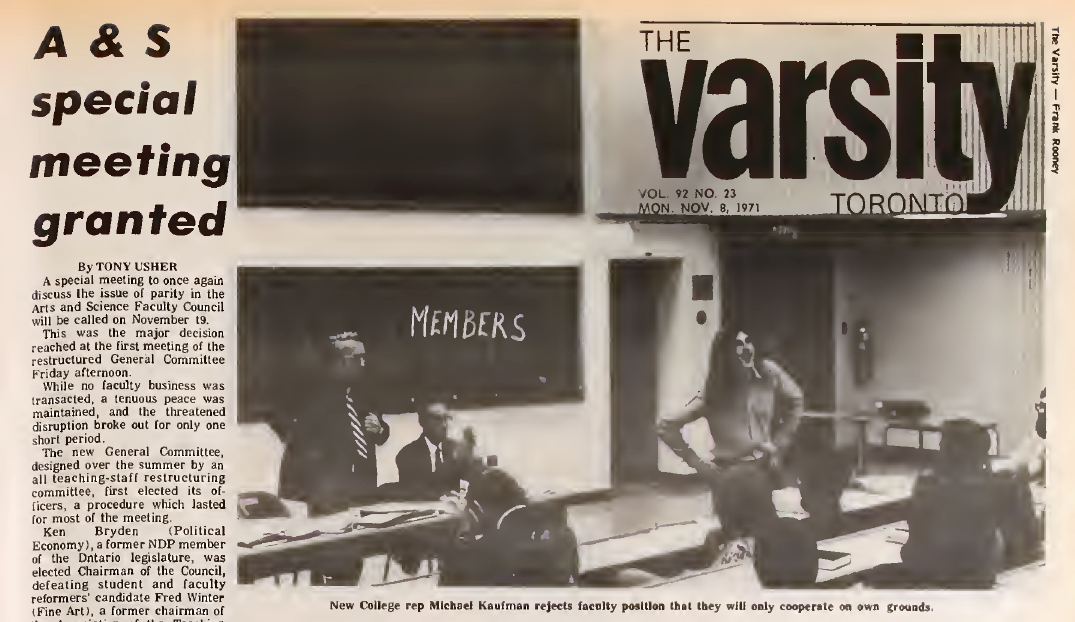

Kaufman’s passion for activism dates back to his time at U of T, where he was elected to the student council in his first year and got involved in various student activist groups.

“It was this amazingly effervescent and exciting time,” he recalls. “Those days were the height of the student movement. When I started in 1969, students had no voice, but we had a powerful conviction that this was our university and we should have a say.

“We created a community within the larger U of T community — which is one of the great things that U of T affords.”

From a campaign for campus daycare to a push for student representation on governing bodies, students advocated to have their voices heard.

“We felt we could define our educational environment and our collective futures, that our responsibility was to create a better future. There was a sense of optimism, which was certainly fueled by the anti-Vietnam War movement, the civil rights movement, the nascent women's liberation movement. It was such an amazing time.”

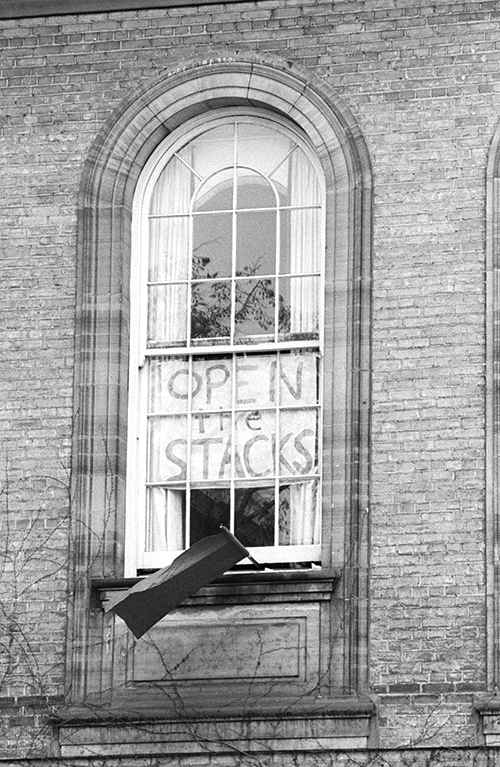

In the fall of 1971, Kaufman decided the student council should tackle a source of contention on campus: Robarts Library.

Though construction of the new library was still underway, plans to limit undergraduate use by reserving direct stack access for faculty, graduate students and fourth-year undergrads prompted protests from the Students’ Administrative Council.

“We developed an ongoing campaign and started speaking out,” Kaufman says. “We had a sleepover in the Sigmund Samuel Library that lasted a couple of nights. There was a big rally at Convocation Hall, and then a bunch of students occupied Simcoe Hall — peacefully. There wasn’t any destruction of property. We were there to be seen and heard.”

And they were. When Robarts Library opened its doors in 1973, all students were welcome.

Kaufman also developed an interest in gender equality at U of T, where he supported the campaign for campus daycare and rallies around abortion rights. He and a friend even enrolled in the first women’s studies course offered at U of T — though he didn’t make it past the first class.

“I’m exaggerating, but looking back, it feels like the two of us talked almost as much as the rest of the class combined,” he says with a grimace. “At the end, the professor came up to me and said, ‘Thank you very much for your support; please don't come back.’ Later, I realized we were recreating the patterns of male domination. We did it in the assumption of support, but there we were taking over. It was a good lesson on entitlement and why it’s important for those in traditional positions of power and privilege to stop talking and start listening.”

I absolutely did not want to write a grim dystopian novel. I wanted to write a book with a sense of hope. As humans, we need to be thinking about how to construct a future that is economically, politically, culturally and socially sustainable. I strongly believe in our capacity to create better futures.

Although his PhD was on socio-economic and political change in Jamaica, by 1980, Kaufman was beginning to study the impact of men’s power and dominant ideals of masculinity. “A lot of my scholarly work on men, leading into my activist work, grew out of my training at U of T.”

After graduating, Kaufman taught at York University for a decade before deciding to pursue activism and public education in 1992.

“There were a handful of men in the world at that time who were working to engage men to support women's rights,” he says. “And I just thought, ‘Someone's got to do this.’ There are now hundreds of thousands of men around the world who have said, ‘I'm going to devote at least part of my energy to supporting women's rights.’ I feel I did what I could; I hope it was a contribution worth making. Now I can return to what I've long dreamed of doing: writing fiction.”

Kaufman’s award-winning debut novel, The Possibility of Dreaming on a Night Without Stars, was published by Viking/Penguin in 1999, followed by The Afghan Vampires Book Club, published by World Editions in 2015. The Last Exit, which hit bookstores last month, is Kaufman’s first mystery and the launch of his Jen Lu series.

In his efforts to create a multifaceted story — both engaging and evocative, fun yet thought-provoking — Kaufman was determined to avoid one thing: hopelessness.

“I absolutely did not want to write a grim dystopian novel. I wanted to write a book with a sense of hope. As humans, we need to be thinking about how to construct a future that is economically, politically, culturally and socially sustainable. I strongly believe in our capacity to create better futures.”