Daniele Iannucci has watched thousands of soccer games and played even more soccer video games. In watching and playing all those matches something struck him — something he’d seen a million times.

Often during televised matches or video games, fans and gamers alike will see pictures of soccer players flash before their eyes amid other important information such as nationality and birthplace as well as physical facts such as age, height and weight.

It occurred to Iannucci that these easily overlooked images possess a lot of power and influence in terms of how we think about nationality.

“Nobody ever talks about these images,” says Iannucci, a PhD candidate with the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Cinema Studies Institute. “When you see them, you just match them up to the player and think, ‘I know who that is.’

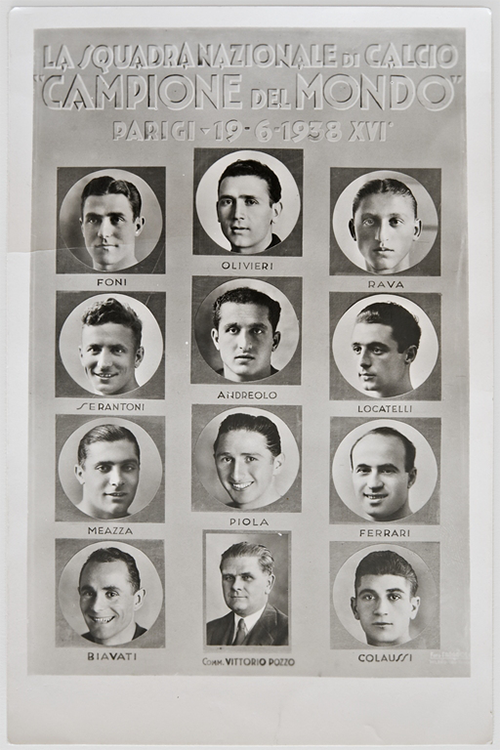

Image: Museo del Calcio, Florence, Italy.

“But these images are really important. They are embedded in these power structures that inform our daily lives.”

To pursue this further, Iannucci is traveling through Europe, exploring historical archives and soccer museums in Switzerland, England and Italy and studying current images from television broadcasts, video games and social media to pursue his dissertation — Portraits and Passports: Sports Media Technologies, World Football, and International Surveillance.

His goal is to explore the history and widespread use of these images, the impact they have on fans, and the influence they have on reinforcing or, conversely, resisting notions of race, ethnicity, citizenship, and national belonging.

Iannucci feels that normally, sharing a document like a passport or another form of identification is a very confidential matter — you share it with a customs officer, or a doctor, or a police officer. “It’s a very private exchange, we only have those in one-on-one situations,” says Iannucci.

Now imagine sharing that info for public inspection on public-facing platforms like television and social media. Suddenly, these images invite a type of public scrutiny that leads to public opinion.

“Think of seeing these player images as microtransactions,” says Iannucci. “Your engagement with the photo ends there, at least you think it does. But when it's accompanied by birthplace, nationality, height, weight, then you start to see this biometric compendium of a nation.”

These images are really important. They are embedded in these power structures that inform our daily lives.

Through his research Iannucci learned the history of these unofficial passports for soccer players goes back well over a century.

“Player images first appeared in newspapers as early as the 1890s, and they were also on the first trading cards in England,” says Iannucci. “Researchers have unearthed reports of English fans walking to the stadium wearing those cards on their lapels or their hats. It became a declaration of identity.”

Much of the images Iannucci is studying originated from the Fédération internationale de football association (FIFA) and its connected soccer governance bodies. Founded in 1904, FIFA is the face of international soccer competition and arguably the most prestigious sports organization in the world.

“It’s synonymous with soccer the same way people say Kleenex for tissue paper,” says Iannucci, noting football governance bodies and sport media industries used these player pictures long before the model for the modern passport was first introduced in the 1920s.

With this historical foundation in place, Iannucci then focused his research on more recent eras such as the 1990s and the early 2000s, with an emphasis on Italy because of Iannucci’s Italian heritage. “It’s also because they've had their own difficult history with players, ethnicity and race,” he says.

One recent example is international soccer star Mario Balotelli, whose photo and information have been seen on every media platform by practically all of Italy. The son of Ghanaian immigrants, but raised by Italian foster parents, Balotelli has been the subject of abuse and racism and been at the centre of endless debate as to whether or not he’s truly “Italian.”

“But even before that, Argentinian and Uruguayan players of Italian descent faced a lot of difficulty,” says Iannucci, believing FIFA’s fluid nationality laws coupled with these public passport images fueled disagreements.

“During the Mussolini years, there were times they were repatriated by Italy. And then afterwards, when they wanted to go back to Uruguay, Venezuela or Brazil, the fascist government at the time would say they really weren't Italian in the first place.”

In fact, FIFA’s influence is so far-reaching Iannucci is also exploring what he called “sports law”— regulations created by FIFA to determine if a player can represent their country in international matches.

According to Iannucci, FIFA “blurs the boundaries between governmental and non-governmental authorities” with their own rules for players representing a national team, yet again shaping the public’s perception of who genuinely belongs to a given country.

And if that wasn’t enough influence, FIFA also figured prominently in soccer video games in the early 2000s, connecting with a new younger generation of soccer supporters.

In early versions of these games, gaming companies used fictional players. “At first, it was made-up names that sound like a certain ethnicity,” says Iannucci. “So if you're going with the Italian team, it's like ‘Luca Spaghetti.’ But then, as you start to get into later games that go into the 1990s and the early 2000s, you have real players with real stats.”

So again players see images and personal information for these players on their phones, tablets and laptops, adding even more depth to FIFA’s influence.

Iannucci hopes to complete his dissertation by the end of 2024. In the meantime, he has this advice for soccer fans tuning into matches or firing up their game console.

“When a player's 'passport' photo comes up ask yourself: ‘Why is it so normal and acceptable to see this type of photograph used so widely in sports, and nowhere else?’

“Think about how, and why, we as spectators are constantly enfolded into that process of checking the 'passport' of athletes, in order to know, and be aware of, who is representing the city, the state or the nation.”