In 1898, an Anglican missionary in Toronto set out for the Rainy River region on the Ontario-Minnesota border. Almost 120 years later, his diary tells a bigger story than he ever imagined, thanks to the Rainy River First Nations and Faculty of Arts & Science students.

In collaboration with the the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre run by the Rainy River First Nations, Professor Pamela Klassen of the Department for the Study of Religion, and a group of student researchers, are creating an interactive website chronicling the journey, and setting it in the context of nation-to-nation relationships in Canada today.

The Story Nations project weaves images, episodic stories as well as historical and contemporary context to draw a line from the early days of interaction between the Ojibwe, missionaries and settlers, to modern day issues such as industrial pollution and Indigenous sovereignty that still shape the region.

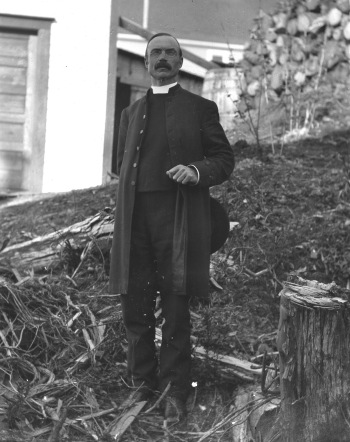

The project’s centrepiece is the diary Frederick Du Vernet kept of his two-week visit in 1898, which unwittingly foreshadows early signs of environmental degradation by loggers and miners while revealing a mix of hostility and respect between Indigenous peoples and settlers.

“It transcends the genre of the diary as a reflection of just one individual’s experience, and speaks to this much broader interaction,” says Keith Garrett, a third-year economics and history student who re-organized the diary as a series of online chapters.

“I don’t think of it so much as a diary as a collection of stories that all take place within this Rainy River world. The diary has literary flair, populated by larger-than-life characters, says Garrett.

“People can go on the website and read a single episode and immediately get a sense of what the diary is about.”

Morgan Preston, a fourth-year history specialist, researched and catalogued more than 500 images spanning pictures from the 1800s to the present day. The line from the past to the present was clear, she says. Getting permission to use the images and showing respect for the people and land they document was the foremost objective.

“This was not an ethnographic exercise,” says Preston. “We’re not going in as outsiders trying to catalogue this culture. The people described in Du Vernet’s diary are a community that is still there, still telling their stories.”

While Du Vernet admitted to feeling a sort of reverence while witnessing Ojibwe ceremonies, his diary is also peppered with references to the “heathens” he had come to convert. The same arrogance was displayed by Christian settlers, who felt their God had given them dominion over the water and land that were so important to Indigenous ways of life.

Within a few decades of Du Vernet’s visit, sawmill dams, overfishing and pollution had led to the collapse of the local fishery that was vital to the region’s Indigenous population, says Nancy Xue, a fourth-year political science and environmental studies student.

Today’s headlines about the drinking water crisis and mercury poisoning on First Nations’ lands underscore how Indigenous people have been bearing the brunt of industrialization since Du Vernet’s time.

“It all ties in with contemporary issues around environmental degradation for First Nations peoples,” says Xue.

Klassen sees the research as a collaborative project that works with the goals of the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre and shares the story more broadly through a digital format.

“It’s a ‘conventional’ research project, just disseminated through unconventional means,” says Klassen, who notes that digital storytelling is becoming increasingly important for historical research.

“Bringing the diary to life in a digital form is important both for what the process has helped us see as researchers, and for the stories it helps us tell to the wider public.” The diary is also the focus of one of the chapters of Klassen’s book, The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land, forthcoming from University of Chicago Press in 2018.

The Story Nations project began several years ago under the Faculty of Arts & Science Research Opportunities Program and Research Excursions Program and is now supported by the STEP Forward program in the Faculty of Arts & Science. All three programs emphasize engaging undergraduate students in research and others forms of experiential learning. Many of Klassen’s graduate and undergraduate students have been intimately involved in the project along the way, including on visits to the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre.

This story was updated to include a link to the Story Nations project, which launched in June 2018.