In 1845, British explorer John Franklin set out to map the Northwest Passage alongside 128 crew members between two ships. They were never heard from again.

Since the mysterious disappearance, a cultural obsession with re-telling the tale — through books, paintings, films and even an AMC series called The Terror released last year — has never waned. While the ships were recently discovered, the exact details of the men’s demise are still unclear.

Professor Mark Cheetham of the Department of Art History in the Faculty of Arts & Science will explore the ways in which weather has been represented on the ill-fated Franklin expedition and other searches for the fabled Northwest Passage, and what that says about our ability to imagine and portray landscapes and climates that are inhospitable, otherworldly and threatening — at least to Western colonial eyes.

Cheetham joins the Jackman Humanities Institute (JHI) next year as a faculty fellow, where the annual research theme is “Strange Weather,” an inquiry into critical discourse on environment and climate. His new project is an extension of his ongoing research and writing on art that addresses landscape, ecology, climate and weather.

Artists throughout history have depicted the land, people on the land, land use — whether it’s agriculture or hydrology or something else.

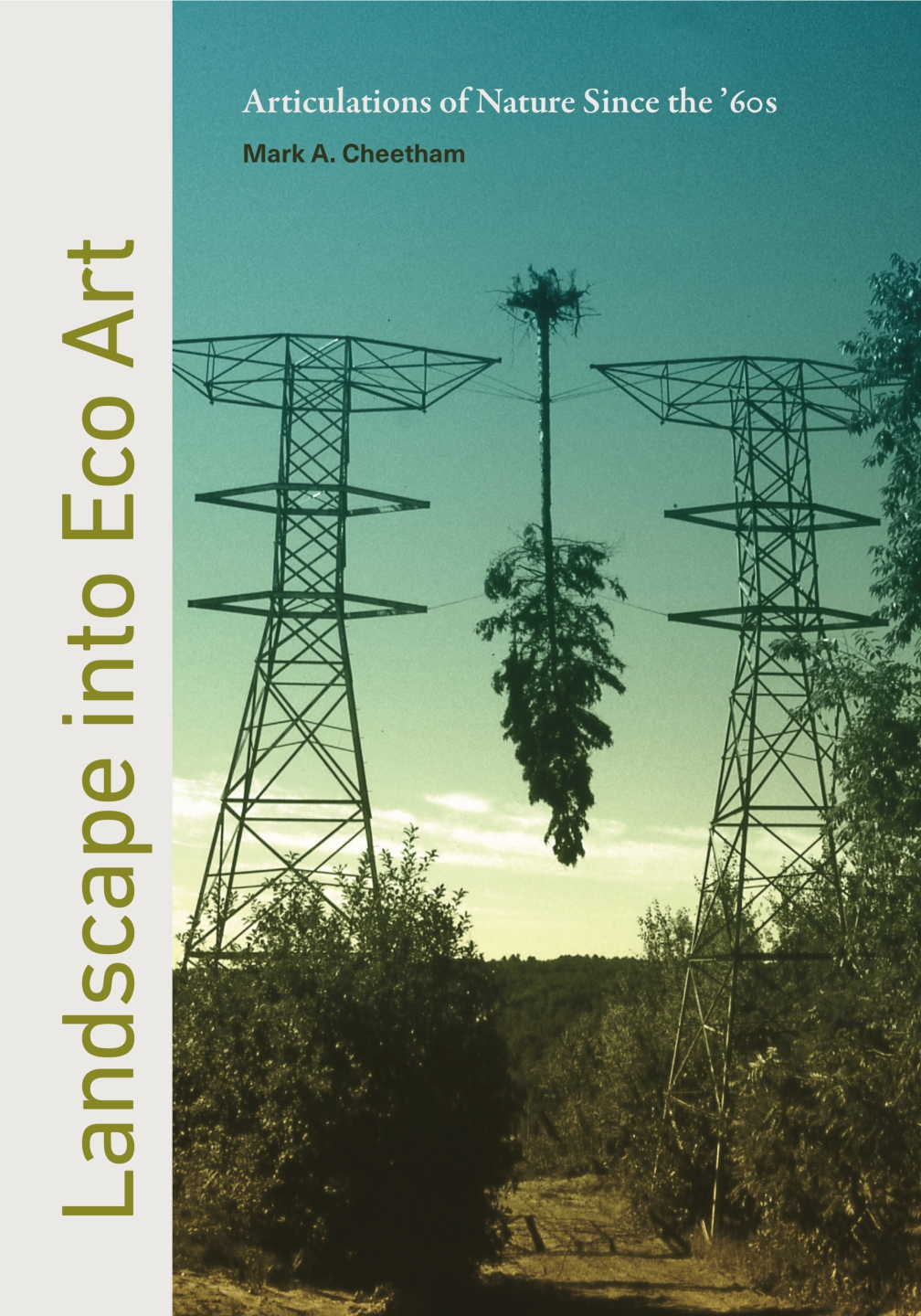

In his 2018 book, Landscape Into Eco-Art: Articulations of Nature since the ‘60s, Cheetham explored contemporary art’s engagement with ecological issues, referencing earlier traditions and genres like the “Land Art” of the 1970s — the most famous example of which is Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) — and the landscape painting traditions of the 19th century.

In his 2018 book, Landscape Into Eco-Art: Articulations of Nature since the ‘60s, Cheetham explored contemporary art’s engagement with ecological issues, referencing earlier traditions and genres like the “Land Art” of the 1970s — the most famous example of which is Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) — and the landscape painting traditions of the 19th century.

The book’s development was closely tied to his undergraduate course of the same name, and his students’ deep engagement in the material did not go unnoticed.

“The younger you are, the more ecological impact matters to you,” says Cheetham. “And there are many contemporary artists — Bonnie Devine, Roni Horn, Pierre Huyghe, to name a few — who are trying to find different ways to engage with these issues, on a material and social level.”

Cheetham’s new work on the Franklin expedition will focus on printed matter — books, periodicals, pamphlets, newspapers — as part of a larger project tentatively titled Weather as Matter and Metaphor, which aims to explore how artworks about landscape and weather can “inform us about the earth’s history and our relationships with the planet,” he says.

“Artists throughout history have depicted the land, people on the land, land use — whether it’s agriculture or hydrology or something else,” says Cheetham.

“I’m now interested in art that depicts weather and what kinds of visual language it uses. For example: in the late 18th and early 19th century, landscape painters started to codify how they would paint clouds. So, you wouldn’t just get random clouds; you’d see cumulus clouds, cirrus clouds, and so on.”

The Franklin expedition was part of a larger trend of public interest in Arctic exploration in 19th century Britain and North America.

“You wouldn’t believe how much Arctic exploration literature there is from that era,” says Cheetham. “Some of these volumes sold upwards of 200,000 copies. That’s broad dissemination. That’s popular discourse.”

Cheetham remarks that U of T’s own Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library houses an extensive collection of 19th century Arctic exploration literature, a valuable resource for his research.

Arctic exploration leads us into a discussion about colonialism in a very potent way.

“Arctic exploration leads us into a discussion about colonialism in a very potent way,” says Cheetham. “I’ll be looking at interviews with Inuit who gave oral accounts of their encounters with Western Arctic explorers, and how that encounter has been pictured in the literature.”

The “metaphor” part of Cheetham’s Weather as Matter and Metaphor aims to explore how we use analogies and metaphors to talk about things we otherwise may not know how to represent. Cheetham’s earlier work explored how analogies such as “Tom Thomson is the Van Gogh of Canada” can structure the ways we experience and talk about art and culture.

“In this new project, I want to see what the analogical relationship between textual and visual descriptions of weather are,” says Cheetham. “How do they work together, particularly in 19th- century illustrated travel narratives? And how are readers supposed to understand those different registers? Is there sometimes a gap between what you’re seeing and reading? I want to unravel that mental process.”

Cheetham’s inquiry is clearly a broad one, so he anticipates benefiting from the cross-disciplinary collaboration that takes place at the JHI.

“In the JHI’s fellowship program — which includes faculty, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students and undergraduates from across the humanities — everybody presents their work to the whole group, so we get feedback. And then there’s the more informal hallway conversations that take place. I hope all of this will sharpen and expand my project. I also look forward to assisting scholars who are in an earlier career stage. I really enjoy taking on a mentorship role; I think it’s an important part of fostering a community.