As the end of the dry season across the Amazon rainforest approaches this month, scientists and researchers are once again assessing the potential loss of life and ecological devastation caused by many linked and interacting factors throughout the region.

The ongoing removal of trees, the clearing of exposed land for farming and severe drought are combining to put the lives of populations — many of them Indigenous to the land — at risk.

Gabriel de Oliveira, a postdoctoral fellow working with Professor Jing Chen in the Department of Geography & Planning in the Faculty of Arts & Science at U of T, describes how an already threatening ecological crisis that had been developing for several years was made worse by the breathing difficulties respiratory challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

What are the linked interacting factors that have created an exceptionally dangerous dynamic in the Amazon?

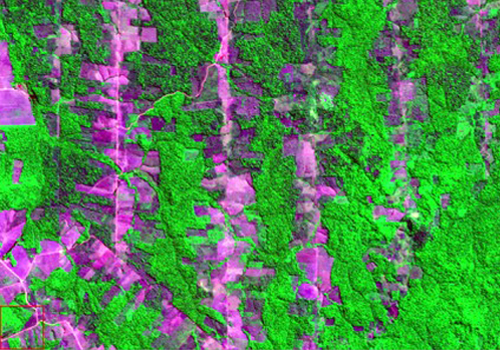

These factors are related to the increased deforestation by land grabbers and settlers, the fire-associated processes of cleaning the land in order to implement agricultural activities such as farming and grazing, as well as a severe drought in the western region this year.

Usually, the dry season is normal, with still a good amount of rain. However, due to climate change, the Amazon has been experiencing some drought events that make the dry season worse, impacting the whole ecosystem and making the fires in the region even more dramatic. Furthermore, sea surface temperatures observed this year in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean have been unusually high.

To what extent is human activity contributing to the situation?

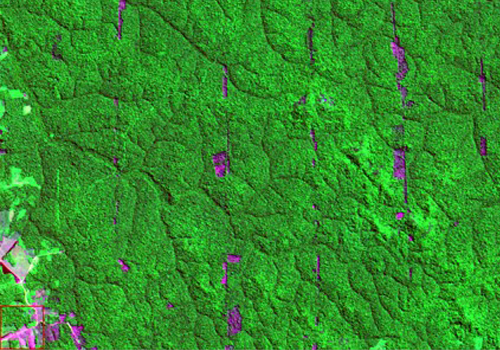

The deforestation and consequent fire-associated processes are caused by humans who clear-cut the mature forest to extract the most valuable tree species, then burn it down and implement agricultural activities such as cattle raising and soybean production. Contrary to what the president of Brazil says, these fires are caused by loggers and big agricultural companies — not Indigenous and native peoples whose lives and livelihoods are endangered.

Under a growing climatic drought threat, felled forest from this year and the 45 per cent of biomaterial that wasn’t burned last year has been fueling an exceptional fire season that is choking the Amazon with fine particulate air pollution.

In an article published in Science earlier this year, you and your colleagues suggested that as the crisis of COVID-19 raged with globally high per capita impacts in the Amazon, relatively little attention has been given to the links between all of these factors that now threaten a social environmental disaster. Has the pandemic both exacerbated and been worsened by an already dire situation?

The smoke arising in large quantities from forest fires is extremely toxic, causing shortness of breath, coughing and lung damage. Previous studies have shown a likely relationship between air pollutants linked to fire — such as the class of miniscule airborne particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometres and smaller known as PM 2.5 — and COVID-19 infection. This suggests that widespread fires could aggravate the current COVID-19 crisis. In the Amazon, for example, fires are responsible for 80 per cent of increases in fine particulate pollution regionally, affecting 24 million Amazonians. So, air pollution will likely significantly increase COVID-19 infections and deaths, with the most devastating impacts among traditional and Indigenous people.

A governance crisis in Brazil created highly visible increases in Amazon deforestation in 2019, and our research shows that pre-existing conditions of deforestation and drought gave rise to fire and the respiratory health crisis that unfolded this year.

Our findings offered a clear warning, while effectively calling for swift action to enact a deforestation and associated burning moratorium in at-risk Amazon areas this year. Such a moratorium would avoid or reduce the catastrophic impacts caused by the combination of smoke and COVID-19.

Will the coming wet season in Brazil provide lasting relief for residents across the Amazon?

The wet season will simply be a "small" pause, with the return of the dry season next year meaning a return to the risk of further loss of life and ecological devastation.

The dry season this year has been devastating not only because of the deforestation and fire records, but also because of the positive land surface temperature anomalies in the region that occurred this year, which made the situation even worse.

The fact is the land surface temperature in the region is still above the historical average – by as much as 2 to 4 degrees Celsius in some areas. This dry season which is supposed to end in December may be extended towards January and February, making the wet season consequently shorter, and bringing several impacts next year.