Sharla Alegria is working on work.

“I care an awful lot about work in general,” says the sociologist who joined the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Sociology as an assistant professor earlier this fall.

“Work is a huge part of our lives, of how we think about ourselves and compare ourselves to others. It’s also a driver of inequality because your job determines whether you can feed yourself and live a nice life.”

Alegria’s research delves primarily into racial and gender inequality. Her work attempts to evaluate how, why and in what form inequalities persist — and what the implications are for workers’ lives.

In particular, she’s taken an interest in the technology sector, studying the career trajectories of women in tech — a project detailed in a recent paper published in the journal Gender and Society.

Alegria’s research found that women with a technical background — say, in engineering or computer science — may start out in technical jobs, but eventually get promoted into managerial positions, often due to the stereotype that women have better interpersonal and communications skills.

While a promotion may seem like a good thing, Alegria says that there are still processes of exclusion at work.

“Having women in leadership positions is important,” says Alegria, “but they tend to get stuck in mid-level manager positions, never going high enough to make meaningful structural differences in the company culture. Plus, they often accept these promotions to avoid dealing with technical co-workers doubting their competence in a hostile work environment.”

Moreover, the notion that technical jobs like engineering do not require interpersonal skills is itself a grave oversight, says Alegria.

“Engineers have to talk to people to figure out how the product being built will be used,” says Alegria. “That communicative aspect of engineering tends to get ignored or partitioned off into someone else’s job.”

Alegria’s interest in sociology was instant when she took an introductory course early in her undergraduate studies at Vassar College, a small liberal arts school in upstate New York.

“I realized sociology could give me a language to talk about inequality. I had never had that. It was what I wanted most in the world. And it’s still the thing I most want in the world.”

Her work on the tech sector is part of her larger interest in so-called “knowledge work” — the industries and labour processes where knowledge and information are produced and shared, all of which are inextricable from technology.

Researching a sector where there is rapid change is “exciting and terrifying,” says Alegria. “In addition to what technology does, I want to think about structural innovations in how we organize work. Sure, we can get cars to drive themselves, but what does that mean for workers?”

Alegria joins a growing consensus that the world of work is changing — and fast. Companies are outsourcing labour to contract workers, “and that means that there are fewer full-time positions with benefits and things like that,” says Alegria.

While there are some advantages to tech companies creating more flexible, dynamic workplaces, “jobs are definitely more precarious,” says Alegria.

Asked what advice she’d give students and young workers entering the job market today, Alegria says it’s “important to collect as many skills as you can. Learn to write well, learn to use data. Learn to give a good, thoughtful presentation. These things are important in any job. And organize for labour rights — that’s a big thing for sure.”

But most importantly, she says, “learn how to learn. The world changes so fast that you need to be able to retool and recalibrate your skills.”

In the meantime, Alegria is conveying her enthusiasm for her research inside the classroom.

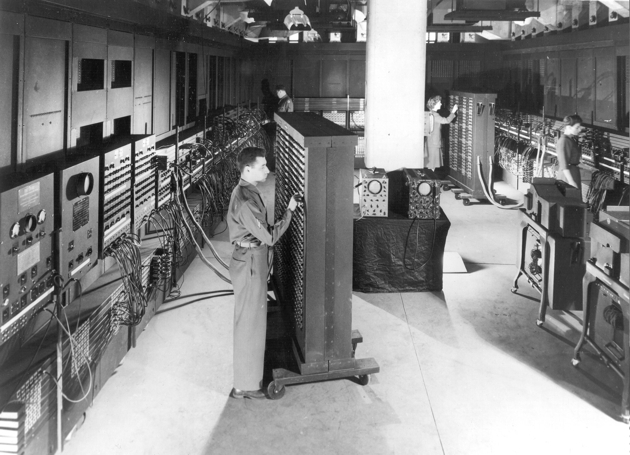

On the first day of her third-year Race, Class, and Gender course this semester, Alegria showed students a photo of technicians, both male and female, working on the first electronic general-purpose computer, the ENIAC machine.

Originally published in Popular Science magazine, the photo was used by the US Army as a recruitment tool in 1946, at which point the female workers were cropped out of the photo — perpetuating the stereotype that computers are “men’s work.”

“When I showed the students, there was an audible gasp,” says Alegria.

“We then had a great conversation about how women were literally deleted from the picture. And, of course, we still only see white workers on the machine. So, I try to get students to consider how we think about who does what kind of work.”

Next up for Alegria: continuing to get to know the University and the city she and her partner — also a sociologist — now call home.

“U of T has one of the top sociology programs in the world, so it’s a very exciting place to be,” she says. “I have so many new colleagues whose work I’ve been reading for years and I’m so excited that I get to connect with them. It’s an incredibly vibrant intellectual space.”