University of Toronto Department of Anthropology Professor David Begun is part of an international team of researchers that has discovered a previously unknown ape species in the Hammerschmiede clay pit in southern Germany — Buronius manfredschmidi, the smallest known great ape. This discovery shows that the diversity and ecology of European apes millions of years ago was more complex than previously realized.

The findings are described in a new study published today in PlosOne.

Madelaine Böhme and her team from the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen discovered the new fossils. The analysis and identification of the new genus was jointly carried out by Böhme and Begun, director of the A.P.E.S. (Ancestors, Paleobiogeography, Evolution, Systematics) lab at U of T.

Buronius lived alongside Danuvius guggenmosi, the tree-living, bipedal great ape that lived almost 12 million years ago and was the earliest evidence of apes walking upright on two legs. Made famous by the Danuvius fossil discovery, Hammerschmiede is now the first fossil site with two different great apes, the species that includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans.

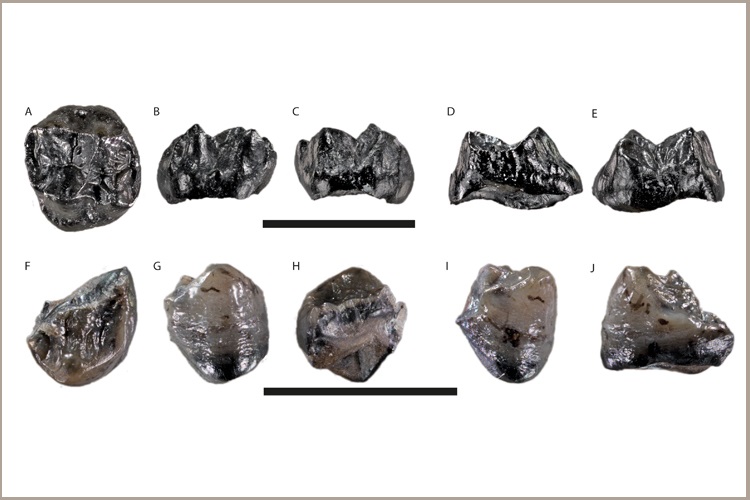

“The Buronius fossils, two teeth and a kneecap, were discovered several years ago near the Danuvius fossils that we found between 2015 and 2018 in 11.6 million-year-old sediment,” says Begun. “Like Danuvius, Buronius probably also lived in trees but was more agile and spent more time in the higher branches. Buronius was also much smaller and had a vegetarian diet.”

"The deposit conditions allow us to conclude that both apes inhabited the same ecosystem at the same time," says Thomas Lechner, excavation manager at Hammerschmiede.

The size of the fossils indicates that Buronius weighed only around 10 kilograms. It was therefore significantly smaller than any of today’s apes, which reach between 30 kilograms (bonobo) and over 200 kilograms (gorilla). It was also smaller than Danuvius, which weighed between 15 and 46 kilograms, closer to a chimpanzee. The body weight of Buronius is comparable to that of the siamangs, relatives of the gibbons from South East Asia.

"Buronius's kneecap is thicker and more asymmetrical than Danuvius's," says Böhme.

This could be explained by differences in the thigh muscles, making it possible that Buronius was better adapted to climbing trees and foraging in the small branches, to avoid competition with Danuvius.

'Buronius' ate leaves and 'Danuvius' was omnivorous

The study of the tooth enamel of both apes from the Hammerschmiede site provides deeper insights into their way of life. In primates, the thickness of tooth enamel is closely linked to their diet. Very thin tooth enamel, such as that of gorillas, indicates a fibre-rich vegetarian diet. Thick enamel, as found in humans, is an indication of an omnivore that consumes hard or tough food using a strong bite.

“The enamel in Buronius is thinner than that of any other ape in Europe and is comparable to that of gorillas. The enamel of Danuvius, on the other hand, is thicker than that of all related extinct species and almost reaches the thickness of human enamel,” says Böhme.

The different enamel thickness corresponds to the shape of the chewing surfaces. The Buronius enamel is smoother and has stronger cutting edges than that of Danuvius, which is notched and has blunt tooth cusps. This shows that Buronius ate leaves and Danuvius was an omnivore.

How 'Buronius' and 'Danuvius' shared a habitat

If two species live in the same habitat, known as syntopy, they must use different resources to avoid competition. The context in which the Hammerschmiede fossils were found is the first evidence of syntopia in European fossil apes. It is likely that the small, leaf-eating Buronius spent more time in the treetops and on branches, say the authors. Danuvius, on the other hand, which was more than twice as large and could walk on two legs, probably roamed a wider area to find more diverse food resources. This is comparable to the current syntopy of gibbons and orangutans on Borneo and Sumatra: while orangutans roam in search of food, the small fruit-eating gibbons stay in the treetops.

'Buronius’s' namesake

In the late 1970s, the dentist Manfred Schmid of Marktoberdorf and the amateur archaeologist Sigulf Guggenmos discovered valuable fossils in the former "Hammerschmiede" claypit. In honor of Manfred Schmid, the new ape species was named Buronius manfredschmidi. The name Buronius is derived from the medieval name of the nearby town of Kaufbeuren, Buron.

With files from University of Tübingen.