A team of physicists have created a new ultrathin, two-dimensional material with unusual magnetic properties that initially surprised them before they went on to solve the complicated puzzle behind the emergence of those properties. As a result, the work introduces a new platform for studying how materials behave at the most fundamental level, the world of quantum physics.

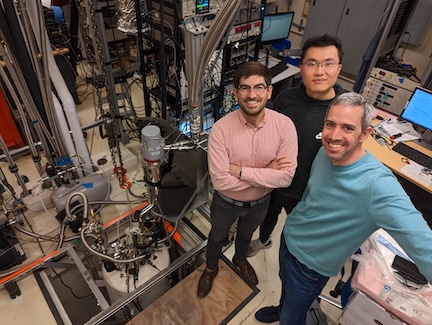

The collaborators were led by Pablo Jarillo-Herrero from the Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. One of the co-lead authors on the paper describing the research is Sergio de la Barrera, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics, Faculty of Arts & Science, University of Toronto, who conducted the work while a postdoctoral associate at MIT.

Ultrathin materials made of a single layer of atoms have riveted scientists’ attention since the discovery of the first such material — graphene, composed of carbon — about 20 years ago. Among other advances since then, researchers have found that stacking individual sheets of the 2D materials and sometimes twisting them at a slight angle to each other can give them new properties, from superconductivity to magnetism. Enter the field of “twistronics” which was pioneered at MIT by Jarillo-Herrero, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics at MIT.

In the current research reported in the January 7 issue of Nature Physics, the scientists worked with three layers of graphene. Each layer was twisted on top of the next at the same angle, creating a helical structure akin to the DNA helix or a hand of three playing cards fanned apart.

“Helicity is a fundamental concept in science, from basic physics to chemistry and molecular biology. With 2D materials, one can create special helical structures, with novel properties which we are just beginning to understand. This work represents a new twist in the field of twistronics and the community is very excited to see what else we can discover using this helical materials platform,” says Jarillo-Herrero, who is also affiliated with MIT’s Materials Research Laboratory.

Do the Twist

Twistronics can lead to new properties in ultrathin materials because arranging sheets of 2D materials in this way results in a unique pattern called a moiré lattice. And a moiré pattern, in turn, has an impact on the behavior of electrons.

“It changes the spectrum of energy levels available to the electrons and can provide the conditions for interesting phenomena to arise,” says de la Barrera.

In the current work, the helical structure created by the three graphene layers forms two moiré lattices. One is created by the first two overlapping sheets; the other is formed between the second and third sheets.

The two moiré patterns together form a third moiré — a supermoiré or “moiré of a moiré,” says Li-Qiao Xia, a graduate student in MIT physics and another of the co-first authors of the Nature Physics paper. “It’s like a moiré hierarchy.” While the first two moiré patterns are only nanometers, or billionths of a metre, in scale, the supermoiré appears at a scale of hundreds of nanometres superimposed over the other two. You can only see it if you zoom out to get a much wider view of the system.

A Major Surprise

The physicists expected to observe signatures of this moiré hierarchy. They got a huge surprise, however, when they applied and varied a magnetic field. The system responded with an experimental signature for magnetism, one that arises from the motion of electrons. In fact, this orbital magnetism persisted to -263 °C – the highest temperature reported in carbon-based materials to date.

But that magnetism can only occur in a system that lacks a specific symmetry — one that the team’s new material should have had. “So, the fact that we saw this was very puzzling. We didn’t really understand what was going on,” says Aviram Uri, an MIT Pappalardo postdoctoral fellow in physics and co-first author of the new paper.

Other authors of the paper include MIT Professor of Physics Liang Fu; Aaron Sharpe of Sandia National Laboratories; Yves H. Kwan of Princeton University; Ziyan Zhu, David Goldhaber-Gordon, and Trithep Devakul of Stanford; and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.

The work was supported by the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Ross M. Brown Family Foundation, an MIT Pappalardo Fellowship, the VATAT Outstanding Postdoctoral Fellowship in Quantum Science and Technology, the JSPS KAKENHI, and a Stanford Science Fellowship.

What Was Happening?

It turns out that the new system did indeed break the symmetry which prohibits the orbital magnetism the team observed, but in a very unusual way. “What happens is that the atoms in this system aren’t very comfortable, so they move in a subtle orchestrated way that we call lattice relaxation,” says Xia. And the new structure formed by that relaxation does indeed break the symmetry locally, on the moiré length scale.

This opens the possibility for the orbital magnetism the team observed. However, if you zoom out to view the system on the supermoiré scale, the symmetry is restored. “The moiré hierarchy turns out to support interesting phenomena at different length scales,” says de la Barrera.

Concludes Uri: “It’s a lot of fun when you solve a riddle and it’s such an elegant solution. We’ve gained new insights into how electrons behave in these complex systems, insights that we couldn’t have had unless our experimental observations forced us to think about these things.”

With files from MIT Materials Research Laboratory.