A new online exhibition at U of T's Art Museum — pleasurehome: desiring queer space — explores the unique textures of queer belonging. Navigating the complexities of ‘queer home’ — artists John Greyson, Evan Sproat, Kaeten Bonli and Shawné Michaelain Holloway explore queer belonging through new works presented in an intimate online space on a monthly basis in a variety of media.

Sonja Johnston of the Jackman Humanities Institute interviewed the exhibition’s curator Logan Williams, a master of visual studies student about his background, influences and his inspiration. pleasurehome: desiring queer space runs until April 30, 2022.

Can you tell us a little about your background?

I began working in the arts at a very young age with a dream of being a recording artist; I had the opportunity to work on making compilation albums for children when I was just twelve. After brief stints on reality television competitions, I was enamoured by musical theatre and began post-secondary training as an actor. I quickly developed a passion for creating sets, costumes, and props, and began to take on more directorial roles upon graduation. My dreams of singing were replaced by making bold and experimental works of live performance that confronted the craft of theatre, as well as social and political issues from sexuality to environmental disaster.

I founded Title 66, a performance collective invested in bringing Montreal audiences an alternative experience of theatre, not yet available in the English-speaking community. Time spent in continual creation mode propelled me to eventually pursue a research-based practice through visual culture and performance studies at the School of Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University. The cross disciplinary nature of the school fostered my pursuit in developing a language for performance and introduced me to visual art discourse in which I could nestle my desire for more research. I began to write, which has become an important part of my practice as a theatre maker and curator, embedding an affectual and emotional response into each project that I undertake.

What inspires you?

Inspiration has always flowed to me through environments and relations. I take cues from the patterns and textures found in natural materials and landscapes, heightened by my upbringing on a farm in a rural town. My childhood was one of constant imagination, using raw materials to create new objects, pretending they were their new incarnation despite a material difference. While my queer identity was in constant negotiation in an environment that negated difference, I became reliant on deeply analyzing social behaviours and relations so that I could perform in ways that would protect me. I have been influenced immensely by this psychological digging, and find in music, theatre, and visual arts a kinship to those early memories of deep excavation, looking for something that is not quite visible but equally palpable. I’m moved by uproarious laughter and heavy sighs, uncontrollable weeping, and the feeling of pure joy. These unparalleled experiences teach us more about our potential to be present in the world, to open to the many extensions of our capacity for being human.

The JHI theme this year is pleasure. What drew you to this theme?

I have always had difficulty with the processual. Plagued by anxieties and the perception of others, making, and organizing artworks has, for the most part, been a topsy-turvy experience of racing to the finish line with bated breath and high blood pressure. I think this is the way a lot of folks have been encouraged to work and live in a world obsessed with outcomes and financial success; we have forgotten that the final product, the presentation, the successful partnership, is only a stunted fraction of the whole experience. And although I remind myself with each new endeavour the importance of pleasure in the process, it seems to be swiftly replaced by learned behaviour: “stress now, relax later.” I was invested in the theme of pleasure as a methodology for fracturing the binary, taking up a radical approach to pleasure to redefine process as a plush place where difficulties can still arise yet aren’t contingent on feeling lesser than or overwhelmed.

'Home' is really complex — it can mean so many things to so many different people. What aspect(s) of "home" inspired your project?

When I was a teenager, my parents were separated and the house that I grew up in burnt down; while they tried to build new lives for themselves, my brother and I were aghast at how quickly everything went up in smoke. The foundation on which we built our identities no longer existed, we felt as though we had been duped by some invisible notion of the importance of a home. Since then, we have both been vagabonds travelling through new cities every few years, letting objects come and go out of the probability that we will eventually be behind the wheel of a U-Haul.

The exhibition responds directly to my own experience, while speaking to this construction of home, made manifest through queer experience and the incongruities of the queer body in a primarily hetero-dominated space. For me, the concept is something that requires more consideration because it has become such a standard in the contemporary conception of identity making and establishing place, particularly in the North American context. How might we shift the visual culture of the home to encompass bodies that have historically been erased or forgotten from the construction?

Did your concept of 'home' evolve as you progressed? If so, how?

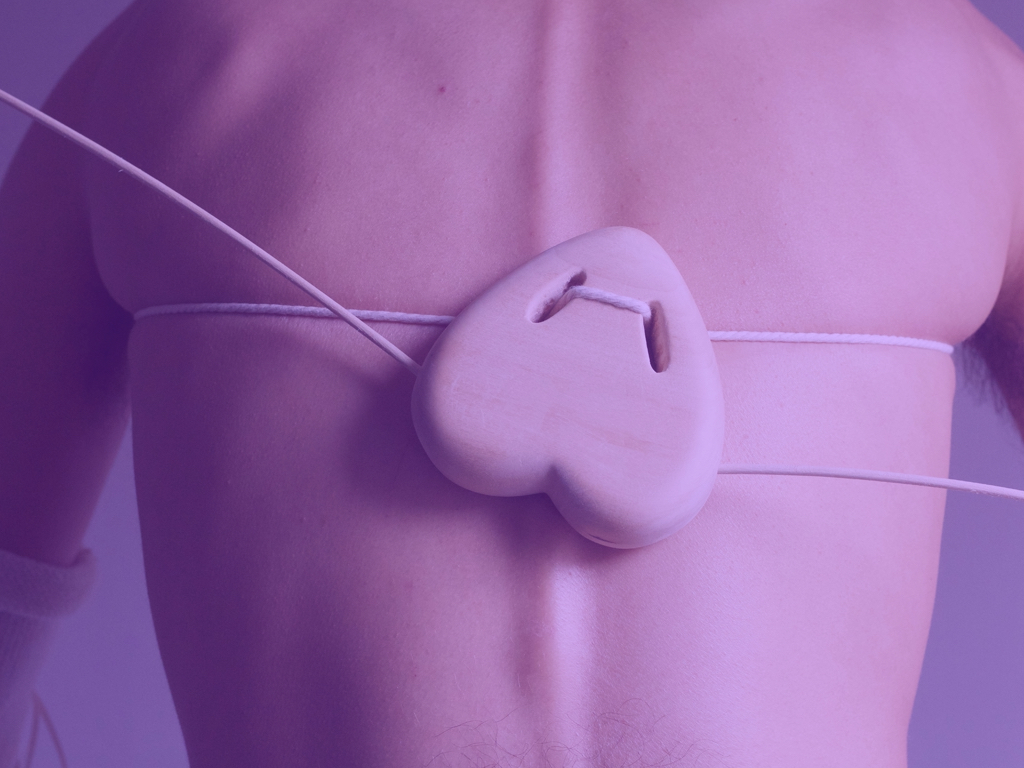

The exhibition was born from the desire to share space with artists and thinkers in unconventional and experimental ways that elided standard presentation practices. It wasn’t until half-way through the planning stages that Catherine Opie’s photograph Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) became the seminal work in which the exhibition came to life. The carvings on her back elicited such an affectual response, I wondered whether it was real or staged, I felt a kinship to a desire so strong to upend the vision of home that one would go as far to carve it into their skin. What emerged was a dialectic between desire and violence: on each new desire is the residue of violence that distorts our desire so we may belong in a state of things. What this means is that we are continually reconstructing our desires to unfold through what is possible in the world in which we live, instead of obfuscating those barriers to achieve desire as it comes to us. This felt not only relevant to the idea of home — the rising cost of housing, the inflation of product prices — but of the queer experience, too. Home is a negotiation between an idea that is proliferated through the collective conscious and a potential to redefine social narratives.

Did your interpretation of 'pleasure' change as you worked on your project? If so, how?

Pleasure in the process was a sliding scale; I wouldn’t say that I achieved the utopic vision I had desired. There are so many working parts in the creation of exhibitions and artworks that it can become a dizzying task to focus on enjoyment through each new hurdle. I would say that pleasure was redefined through my relationship with the artists and their continued commitment to making works that not only responded to the exhibition prompt, but to the contemporary moment of lockdowns and restrictions that plague us still. Through Zoom, there was a resounding energy that emanated between us, it was intoxicating and wonderful and for those few hours, time would stop as we sat in a conceptual dreamworld. In relations comes potency: coming together can heal wounds and ease discomfort through uncertain times, culminating in pleasurable moments that are as fleeting as anything else. For me, it was harnessing that energy to pour into other aspects of pandemic life that kept the pursuit of pleasure at the forefront of the project.

What drew you to the artists in your exhibition?

Selecting the artists was a very organic process. Based on research, I was able to create a list of queer artists who were working with the idea of home and childhood, identity, and place, and from there conversations began. I wanted to commission artist from different cities in the hopes of a multi-vocal investigation of home. Evan Sproat and I have worked together previously, so I knew his work would speak strongly to the theme. Kaeten Bonli was a connection through mutual friends who I met years ago, and we continued to be in touch. I was familiar with Shawné Michaelain Holloway’s work through my experience in performance and theatre and John Greyson had long been a hero of mine that I had always dreamed of working with.

What are your plans when this exhibition is over?

I’m finishing up the last year of my graduate degree where I will be curating another show. The exhibition will be in the Art Museum and functions as a companion piece to pleasurehome. While this iteration focuses on pleasure and desire, my upcoming graduating show will focus deeper on the violence inherent in the queer experience, integrating my own personal narrative more distinctly into what I’m calling a curatorial ‘mise-en-scene.’ I will also be working on developing a performance piece with Title 66 that confronts the climate catastrophe through a durational, experimental work that we hope to develop over the next four years.

About the exhibition

pleasurehome: desiring queer space — a virtual exhibition inspired by Catherine Opie — features John Greyson, Evan Sproat, Kaeten Bonli and Shawné Michaelain Holloway and spotlights one artist a month from January 6 to April 30.

Presented in conjunction with the Jackman Humanities Institute’s 2021–2022 research theme, Pleasure, pleasurehome: desiring queer space is a co-production of the U of T Art Museum and the Jackman Humanities Institute.