Iran is home to some of the world’s oldest and richest artistic traditions. Painting, literature, film and music all continue to play important roles not only as sources of pleasure, but of social and political influence in both the country and its worldwide diaspora.

Recently, an innovative multiyear partnership was signed between the University of Toronto and the Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. The latter was established in 1990 with the ultimate aim of publishing a reference work that covers all aspects of Iranian history and culture. Under the partnership, researchers will gather and share a wealth of information on projects exploring two important artistic topics: Iranian women poets and Iranian cinema.

The principal investigator on both projects is Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, a U of T professor of Historical Studies & Near & Middle Eastern Civilizations. Tavakoli-Targhi is also the inaugural director of U of T’s Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Institute of Iranian Studies, which opened last year.

“In the past decade, the University of Toronto has emerged as the most important site for the study of Iran,” he says. “The new institute has over 20 faculty with twice as many graduate students, and there is a vibrant Iranian community in Toronto and Canada, all linked to sources of intellectual and artistic creativity. So it has been rather timely for the University to initiate a project like this.”

The Encyclopedia Iranica will publish the digital research compendia on both subjects via its website, and the material will be freely accessible to anyone — not just academics, but those who may wish, for example, to organize readings or film festivals.

Until recently, the general academic understanding was that Iranian literature has been exclusively the domain of men. But because of work done in the past 40 years by literary scholars, it is now known that women have been writing poetry since as early as the 10th century.

The first project, formally titled Iranian Women Poets, will shine a bright light on writers whose work has often been overshadowed by that of better-known male counterparts such as Rumi, Hafez, and Omar Khayyam.

Tavakoli-Targhi notes that poetry remains an important part of everyday life in Iran. While people in many other countries pay little attention to their own poetic traditions, Iranians frequently recite poetry and seek ethical guidance from it.

“Until recently,” he says, “the general academic understanding was that Iranian literature has been exclusively the domain of men. But because of work done in the past 40 years by literary scholars, it is now known that women have been writing poetry since as early as the 10th century.”

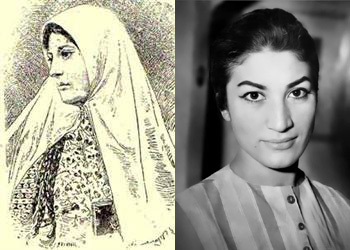

Significant figures here include Rabi‘ah Balkhi, a 10th-century poet; Mahasti Ganjavi (born circa 1089); Tahereh Qurrat al-‘Ayn, a 19th-century writer who was not only a poet but also a women’s rights activist and theologian; and Forough Farrokhzad, whose courageous work has been revered by many since her untimely death in 1967.

The second digital compendium, Iranian Cinema, is related to the first in that both women and poetry have played key roles in the development of Iranian cinema.

“Iranian cinema has distinguished itself from the cinema of the rest of the world, because it is informed by poetry,” says Tavakoli-Targhi. “And some of my colleagues have argued that in the past several decades, cinema has replaced poetry as a form of Iranian self-expression. What is also interesting is that in Iranian cinema, women directors, producers, actors and so on are gaining more public attention. They’re following what one of my colleagues has called the ‘cinema of empathy’ — a kind of cinema where women are emerging as the universal subject, as someone the audience would want to be like. Because they are caring figures: attending to family, and also to their community and nation.”

I often think of the COVID age as the simultaneity of spring and fall, because you have the withering away of all these community networks that we used to have — but also the blooming of a new kind of connection.

In recent years, filmmakers such as Rakhshan Banietemad and Abbas Kiorastami have become known to western audiences. But as Tavakoli-Targhi notes, the field has a long history. “In the early decades of the 20th century, Iran became a site for creative artists from Russia and Eastern Europe to come and do really good work. You saw them coming and creating, in the same way that European immigrants to the United States created Hollywood,” he says.

Tavakoli-Targhi is excited that the new resource projects will be truly international, with contributions not only from the many linguistic and cultural groups found within Iran, but also through the variety of researchers studying these topics abroad.

He is currently convening a Canadian Society for Iranian Studies, and has organized a regular Friday seminar series that has attracted close to 4000 attendees. An event planned for Nowruz (Iranian New Year) in late March will also highlight women poets.

Tavakoli-Targhi celebrates the recent surge in cultural knowledge exchange that is fuelling these new initiatives and is poised to give rise to others.

Says he: “I often think of the COVID age as the simultaneity of spring and fall, because you have the withering away of all these community networks that we used to have — but also the blooming of a new kind of connection.”