In their study of human societies, anthropologists have long been concerned with death and violent conflict. But they have had less to say about murder: the unlawful and malicious taking of human life.

All semester long, first-year undergraduates in a provocative new course have been studying why this is so. Taught by Naisargi N. Davé, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology, Murder & Other Deathly Crimes shows how murder’s frequent origin in societal oppression makes it a perfect subject for anthropological study.

As the class wraps up, Davé’s students have been left with a new view on this nightmare-inducing phenomenon.

“This course completely changed my perspective on murder and crime,” says Mahbano Ibrahim, a member of Woodsworth College. “There are so many systemic problems that lie behind it, such as the oppression of women, racism and others. Looking at murder from an anthropological perspective opened my eyes to all of these problems in our society.” Her classmate July Hu, also a member of Woodsworth College, agrees. “My understanding and definition of murder is really different. I used to only think of it on a physical, and not a social level.”

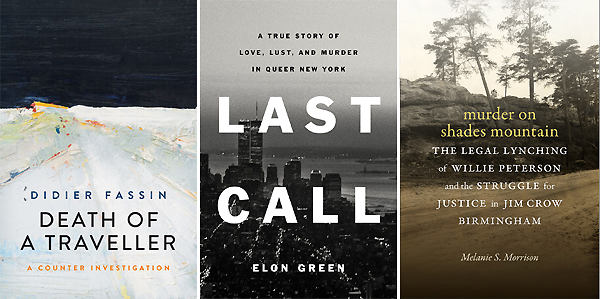

The texts they have been studying reflect that conception. Didier Fassin’s Death of a Traveller recounts the police killing of a member of the French Traveller community; Elon Green’s Last Call recounts the serial murder of gay men in 1990s New York; Maggie Nelson’s Red Parts explores the femicide of her own sister; and Murder on Shades Mountain is about the wrongful conviction of a Black man named Willie Peterson, which occurred decades ago in the Jim Crow south.

The course shows that not only victims, but those accused — rightly or wrongly — of killing them can be viewed as the most tragic products of an unfair society.

“The different cases we’ve analyzed show that repressed trauma and personal issues often influence the killer’s actions,” says student Dorsa Ahmadi, a member of Trinity College. “They have been subjected to horrible things themselves. And when the pain is too much, they end up acting irrationally and causing terror and chaos.”

One idea discussed in the class is French philosopher Marc Crépon’s notion of “murderous consent,” whereby members of society are asked to confront the ways they indirectly encourage murder by not helping to mitigate the social harms that produce much of it.

Students expressed particular enthusiasm for a text written by Umaima Miraj, currently a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Sociology. It references the moral complication of a decades-old case involving women in Pakistan convicted of killing their violently abusive husbands. Did such women deserve to be called murderers, in the way that cold-blooded psychopaths are?

Even murderers whose motives appear purely psychological present us with social issues worth exploring. The students are presenting podcasts for their final projects; Hu’s is on American serial killer Ted Bundy, convicted of murdering scores of young women during the 1970s.

The case caught Hu’s eye because it resembled one that took place in her home city of Shanghai, where the murderer’s good looks resulted in a kind of twisted popularity for him. “So many people discussed his looks,” Hu says. “But why was his appearance considered more important than his crimes?”

Indeed, our society’s fascination with murder is tied to our collective obsession with good looks, fame and celebrity: like reality television, murder is a common springboard for escapist storytelling.

After all, fictional murder mysteries have long been one of the most popular genres — and it is appropriate that students are working on podcasts, as many are fans of the true crime podcasts that are so popular today. Why does murder captivate us so? How can something so horrible be fodder for entertainment, even gallows humour?

I have always felt that death was something so far away from me,” she says. “I would always read about it as an outsider. But after taking this course, I feel more connected to the people we have studied. I believe that understanding death can make for a better life.

“We’ve definitely spoken about this in class,” says Ibrahim. “We discuss whether murder is fetishized or even glorified in popular culture. We haven’t reached a conclusion about why — but it’s perhaps not surprising that it’s a popular topic, since murder and violent crimes are in the news every day.”

Humanizing victims is an important part of the class as, too often, news accounts of killings can be cold and impersonal. “Identifying the reasons behind murder is important,” says Ahmadi. “It determines what makes a person ‘killable,’ which is something Professor Davé emphasizes. A person deemed killable is someone who has their humanity stripped away from them, in a sense.”

There is no question that this material can be disturbing, a fact Davé points out in her syllabus. She warns students to practice self-care when reading accounts of murder and has been, in the words of Ahmadi, “very supportive” in guiding students through their coursework.

The course is structured to minimize trauma; one way in which it does this is by encouraging communication. Most of us read accounts of real murders on our own, then have to deal in solitude with what we have learned. In this class, however, online discussions have followed every reading. “Those always made me feel better,” says Ibrahim. “When I was infuriated, I learned I wasn’t the only one who felt that way.”

In the end, murder is an all-too-common form of death — and death, a central concern of anthropology, is something that comes to all of us in the end. Hu was enormously grateful for the chance to contemplate this.

“I have always felt that death was something so far away from me,” she says. “I would always read about it as an outsider. But after taking this course, I feel more connected to the people we have studied. I believe that understanding death can make for a better life.”