When Claire Battershill took part in the Printing Fellowship Program at Massey College in 2009, she discovered its cast iron printing presses were far more than simply relics of a bygone era of printing.

For many women writers and printers, letterpress printing embodied a liberating spirit, as well as the freedom of artistic control that still draws and inspires artists and writers today.

“There’s definitely a romance about it,” says Battershill, an assistant professor cross-appointed to the Department of English and the Faculty of Information. Her book, Women and Letterpress Printing 1920–2020: Gendered Impressions will be released in July.

The book explores the relationship between gender and literary letterpress printing from the early 20th century to the beginning of the 21st, as well as the ongoing presence, and even revival, of the letterpress in today’s digital age.

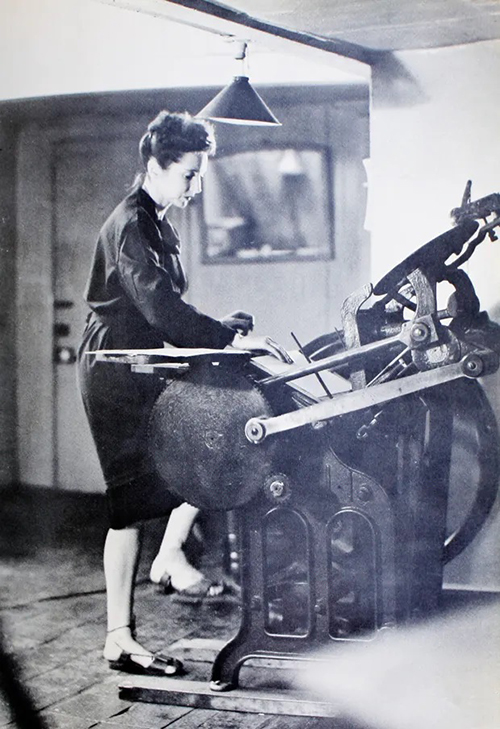

Letterpress printing involves taking blocks of text or images and placing them on a raised surface, similar to a rubber stamp. Ink is applied to the raised surface and then paper is pressed directly against it to transfer the text or image.

Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century, letterpress printing was the standard form for printing until the 19th century, though it remained in wide use for books well into the 20th century, when more modern printing methods took over printing books and newspapers.

“It was a pretty labour-intensive process,” says Battershill, adding that the two steps of typesetting and then printing would take countless hours. “I saw how slow it was and how hard it was to do,” she says speaking from her own letterpress experience. “As an amateur printer, it would take me at least two days of work to typeset and print a small run of a single poem.”

Battershill is fascinated by women writers who used letterpress printing to take full control of both their writing and the production of their work — writers like Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), who along with her husband, Leonard, founded The Hogarth Press in 1917.

“Woolf said, ‘The editors told me to write what they liked. And I said, no, I'll publish myself and write what I like,’” says Battershill.

Anaïs Nin (1903-1977), the French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist and writer of short stories and erotica, created the Gemor Press in New York in 1942 in response to the Second World War disrupting the distribution of her books by large publishing companies.

“She came to the conclusion that it allowed her to think more precisely about what she called ‘the essential words,’” says Battershill.

The surrealist writer, poet and political activist Nancy Cunard (1896-1965) was a self-taught printer who wrote a memoir about the experience of running her own printing house called These Were the Hours: Memories of My Hours Press, Reanville and Paris, 1928-1931.

Battershill was intrigued by how letterpress printing forced writers to stop and reflect on their poetry and prose, in addition to giving them full artistic control.

“A lot of writers comment that it really slows you down,” says Battershill. “It focuses you on one letter at a time. So this idea of breaking language down into tiny little units seems to change the way they think about the words they're writing.”

Would Battershill ever want to publish a book of her own using letterpress printing?

“Yes, I would, though I shied away from doing it in the past, partly because, as a writer, I find it painful to imagine spending so much time with my own work,” she says.

Battershill’s book also investigates why the letterpress still holds so much charm, and how its role has shifted over time, moving from the dominant commercial printing technology to the preferred tool for fine artists, writers and poets.

She believes using a letterpress is part of a resurgence of hand-based arts, like knitting or calligraphy.

“We don't have to do these things manually, but there is a hobby community that connects around hand practice and handwork,” she says. “In a similar way, contemporary letterpress communities are at the intersection of fine art, literature and crafting.”

As well, Battershill comments about the continued appeal of letterpress for women and even groups involved in protests — reflecting the ability to print and spread a message in a genuine and uncensored way. She notes that several Black Lives Matter posters were created through letterpress printing.

And letterpress continues to be a conduit for artistic expression.

The printing press can seem like an antiquarian technology that belongs to an earlier time, but there’s something in the contemporary world we can learn from these older technologies.

In her book, Battershill mentions Ladies of Letterpress — an international trade organization for letterpress printers and print enthusiasts that promotes the craft of letterpress printing and encourages the voice and vision of women printers.

She also highlights the work of Norwegian artist and graphic designer, Ane Thon Knutsen, whose art comes from her personal letterpress studio.

“Her work is letterpress interpretations of Virginia Woolf,” says Battershill. “She creates room-sized installations of her stories where she'll print one or two words per page, and then you walk through the room. It's like you're walking through the story.”

Excited about the book’s release, Battershill hopes readers of Women and Letterpress Printing 1920–2020 will stroll through history and take from it a spirit of, “‘I'm going to make something on my own and I'm going to do it in the way I think is the right way,’” she says.

“The printing press can seem like an antiquarian technology that belongs to an earlier time, but there’s something in the contemporary world we can learn from these older technologies.”