At the dawn of revolution, an Iranian girl channels her fear and frustration through heavy metal music, while an American high school student numbs her pain with pills. A teen mother in Africa struggles with her new role; a Toronto goth gets too close to her English teacher; and the daughter of a funeral home owner comes to term with her own queerness, while enduring a dysfunctional home life.

Welcome to the scrappy, rebellious and often shocking world of graphic novels — one which steadfastly refuses to look at things as they should be, and instead concentrates on what they are.

The relentlessly frank quality of what Judith Taylor calls this “outlaw genre” is what drew her to design and teach a course called Feminist Graphic Novels almost ten years ago.

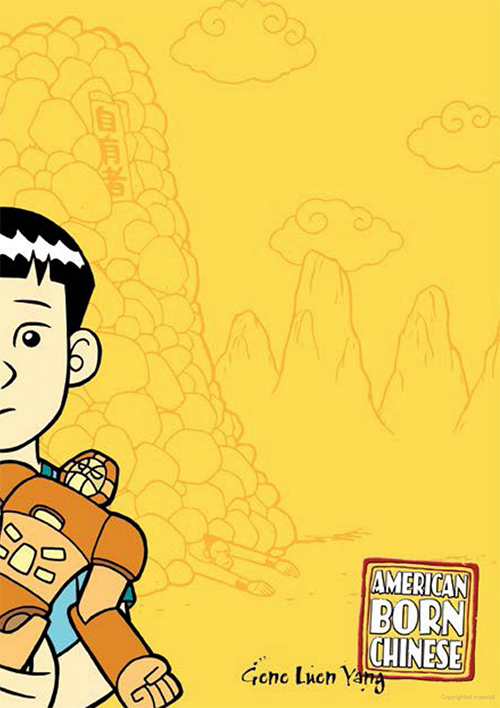

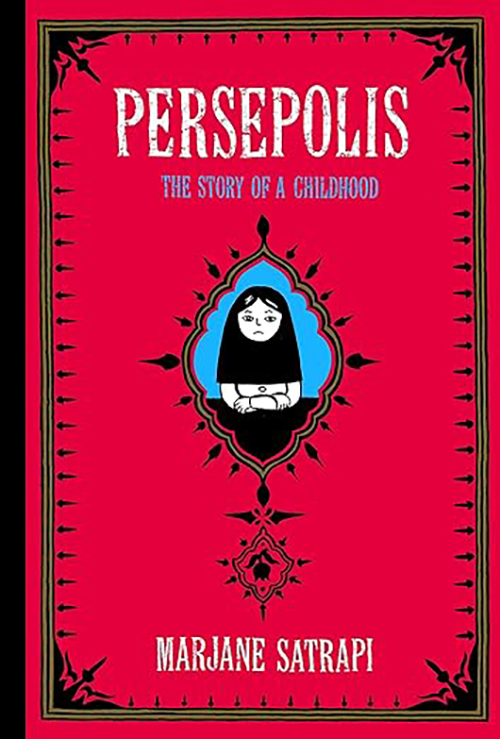

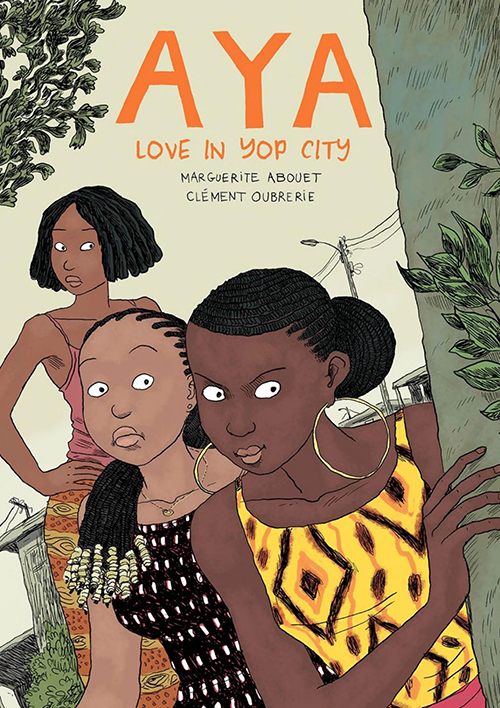

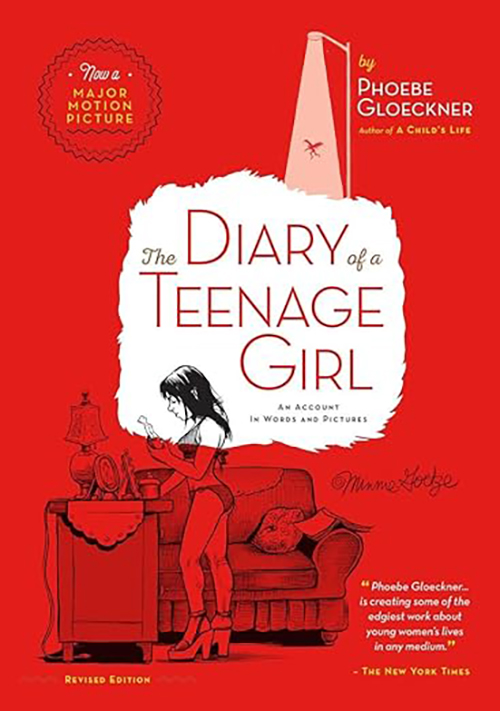

All the books in this year’s syllabus tell different coming of age stories from around the world. They all deal with what Taylor calls “the inadmissible”: hard truths about humans that we are often afraid to confront.

“These authors are asking, ‘would you still respect me if I told the truth, even if it makes me look bad? Even if I am still working out some of my own prejudices?’” says Taylor, an associate professor at the Women & Gender Studies Institute and the Department of Sociology. “Let’s have that discussion, and see how humbling it is to be honest with ourselves.”

The term “graphic novel” was coined as far back as the 1960s, but the genre gained wide popularity in 1986 with the publication of Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Holocaust memoir Maus.

The books are essentially novels told in comic-strip form. But unlike other fiction, which is increasingly fettered by risk-averse publishers, graphic novels still have the raw, psychologically penetrating quality of the most exciting literature.

Many of them have been banned, whether by governments, schools or libraries. Yet several of those that Taylor is teaching this year — most notably, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi and Fun Home by Alison Bechdel — have also been reproduced successfully on film, stage or television; indeed, they have become modern classics.

At the same time that Taylor was developing her course, Jeffrey Newman, librarian at New College’s D.G. Ivey Library, began amassing a collection of almost 300 graphic novels. (Robarts Library, University College and Victoria University’s Pratt Library also have large collections). It’s a fantastic resource for students who may not otherwise have access to these important titles.

“We’ve tried to concentrate on graphic novels written by women or non-binary people,” Newman says. “We worked with a Toronto graphic novel store called The Beguiling to build the nucleus of our collection, bringing in a lot of queer and racialized authors, and covering a whole range of experiences.”

Newman adds the visual aspect of graphic novels amplifies their power. “These authors are pushing at the edge of what it means to be human, and how lived experience is valued in our culture. Their work engages you in a completely different way than other literature does.”

The library hosts an annual lecture with a visiting graphic novelist. On March 28, Palestinian-American artist Leila Abdelrazaq came to discuss her book Baddawi – a moving account of her father’s experience living in a refugee camp in Northern Lebanon after his expulsion from Palestine in 1948.

The panel was moderated by Taylor, who pointed out that Baddawi features a loving portrait of a parent — something not frequently featured in the books in her syllabus.

“Can you love a parent who has done bad things? Yes,” says Taylor. “There’s a complexity that is mirrored in these texts that you can’t get in a lot of other genre.” She goes on to say that reading these stories of vulnerability and survival can often be a better preparation for life than the lessons found in traditional disciplines such as sociology, law and medicine.

“Students in Women & Gender Studies are going to work in rape crisis centres. They might be teachers of students who want to tell them everything that’s happening in their lives. And so,” she asks, “what builds the stamina for that?” The answer can often be art – especially when artists are permitted to tell the truth.

This is particularly important for artists who depict women’s characters, which have often been subject to impossible standards of moral purity. Graphic novels, however, allow for a more realistic, complex portrayal of women’s lives. Newman holds up a sample title that mocks the saintly stereotypes found in other art forms: it’s called, simply, Strong Female Protagonist.

By contrast, the girls and women of graphic novels ask, as Taylor says, “What does it mean to protect the possibilities of my life — how I see it, and what I get to do in it? Feminism can mean, as it does in the case of Marjane Satrapi, privileging one’s artistic practice instead of taking care of one’s parents. And saying: this is a decision I have to work through, and I encourage you to be in conversation with me about this work.”

Levon Karakoyun affirms that this kind of ambiguity lies at the heart of graphic storytelling. Currently completing a master’s degree at WGSI after completing a bachelor’s degree there, he remains impressed by the texts he read in Taylor’s course, which he took in his undergraduate years.

“Graphic novels encourage us to engage in practices of reading that pay attention to the possibilities, desires, and wounds that make up the subtle interconnection between words and images within these texts,” he says.

“Rather than asking us to arrive at definite conclusions, the texts motivate us to read beyond what we think we ‘know’ about these stories. In this sense, they “open up the space for us to hear and pay attention to what ‘cannot be said’.”

With their humble roots in comic books, graphic novels are perfectly placed to embrace human imperfection. “I think they provide beautiful instruction for how to be a sensitive, durable person who gets disappointed and keeps going,” Taylor says.

“Collectively these books are saying, your imagination is your best bet for deciding that life is worth it. I think that’s a great gift.”