As a writer, Linda Rui Feng inhabits two very different worlds.

In her role as associate professor in the Department of East Asian Studies at the Faculty of Arts & Science, she is an acclaimed cultural historian who regularly pores over maps, geographical treatises and other ancient documents to reveal the truth about life in medieval and early modern China.

But when she writes poetry and fiction, she moves inward: much of the truth she reveals there is psychological and emotional, rather than literal.

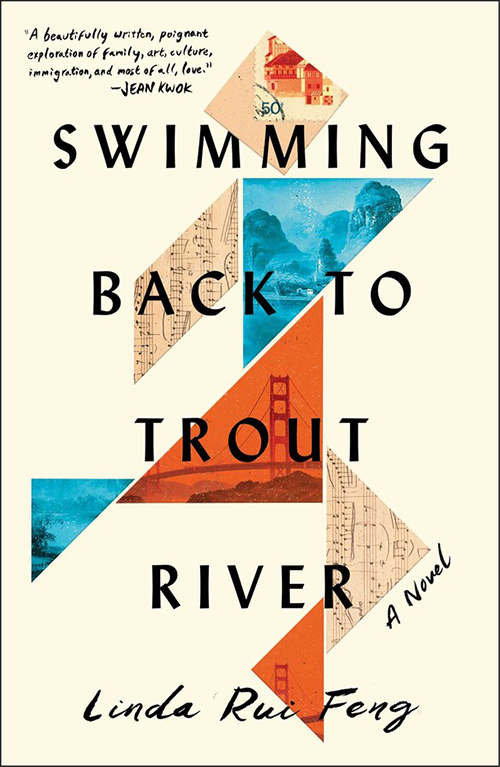

This month sees the release of Feng’s first novel, Swimming Back to Trout River. The book tells the story of a married couple, Momo and Cassia, and an aspiring musician, Dawn, as they each make their journey from China to the United States variously as student, spouse and artist in the 1970s and 80s. A parallel narrative involves Momo and Cassia’s young daughter Junie, whom they left behind in a small Chinese village to be raised by her doting grandparents.

Rave reviews from Publisher’s Weekly, Booklist and the Kirkus Reviews attest to Feng’s ability to create sensitive, relatable characters, while showing how events in the interval of ten years from the 1960s to the 70s known as the Cultural Revolution reverberated throughout the characters’ lives.

For the period I study academically, there is never as much material as you would like. So my job is more to play detective, and make up for those missing pieces. With more recent history, the challenge is in the selection process — to filter out what you need from a relatively abundant set of materials. These skills are both part of the historian’s craft.

“If you write anything multigenerational about mainland China,” she says, “it’s very difficult to avoid that time period. We’re still in the process of trying to understand the emotional impact of those years.”

Born in Shanghai, Feng emigrated to the United States in her early teens, and has long moved between two worlds personally as well as professionally.

“One thing I really like about fiction writing is that I get to think in terms of ‘what ifs’. I always wondered, what would the opposite of my experience have been like — the experience of someone who stayed put?”

Too young to have witnessed the Cultural Revolution herself, Feng grappled with the idea of whether she could properly describe it; when she was a child, one of her aunts told her that her generation would never be capable of true understanding.

“But I always felt there was something really worth puzzling over about those ten years,” she says. “Not in an academic sense — I was more interested in the micro-histories, the way that something gigantic like this might play out in less prominent lives.”

Later in her life, Feng found herself at dinner with an author of what’s known in China as “scar literature” -- a trauma-infused genre that arose in the artistic community after Mao’s death. “This author said that perhaps only my generation would be able to understand what had happened, since we have the privilege of distance,” Feng says. “And of course I have double distance, physical as well as emotional.”

Feng’s academic work usually takes her much farther back into Chinese history: her previous book is a monograph on the Tang Dynasty, which ruled well over a thousand years ago. She says that where researching modern and ancient history are concerned, “two different dynamics are at play.”

“For the period I study academically, there is never as much material as you would like. So my job is more to play detective, and make up for those missing pieces. With more recent history, the challenge is in the selection process — to filter out what you need from a relatively abundant set of materials. These skills are both part of the historian’s craft.”

Writers are often told to write what they know, which Feng certainly does: there is no question that her books are deeply informed both by her academic training and her own life experience. Still, her guiding principle as a professor and fiction writer is always to chart worlds that for her remain as yet undiscovered.

Says she: “I’m drawn far more to the things I don’t understand, than to those I do.”