From scholarly and literary inquiry and analysis to critically acclaimed non-fiction, members of the A&S community published an incredibly diverse range of books. Here are just a few that can expand your knowledge, understanding and imagination.

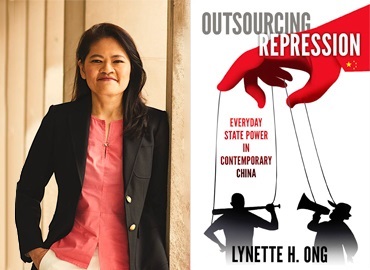

The surprising story of China’s gangs as government allies

When Lynette Ong began researching urbanization in China, she was taken aback at what she found.

The Department of Political Science professor, jointly appointed to the Asian Institute at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, concluded that Chinese cities were growing at a rapid pace: farmland on the outskirts of municipalities such as Beijing and Shanghai were being steadily replaced by new construction.

But the human price was high. Houses were being demolished to make way for high-rises and their owners evicted — victims of intimidation, beatings and arson carried out by thugs and gangs who Ong discovered were instrumental in helping the government meet its urbanization targets.

Her findings are documented in Outsourcing Repression: Everyday State Power in Contemporary China — an award-winning book that has been hailed as an essential contribution to our understanding of Chinese politics, economics and human rights.

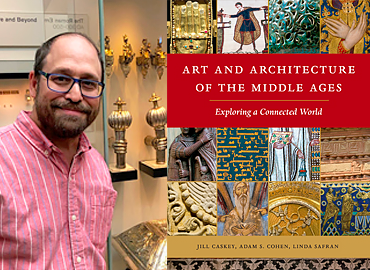

The beauty of daily life in the Middle Ages

When looking at the art of places and peoples in the medieval world, there’s so much more than cathedrals and castles.

That’s why Adam S. Cohen, an associate professor in the Department of Art History, joined professors Jill Caskey of the Department of Visual Studies at U of T Mississauga and Linda Safran of the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, and created the textbook Art and Architecture of the Middle Ages: Exploring a Connected World.

Spanning over 12 centuries of artistic creation from about 300 to 1400 CE, and covering Europe, western Asia and North Africa, the book is 400 pages with over 450 colour illustrations of sculptures, pottery, manuscripts, textiles, paintings and buildings.

To complement the book, Cohen and his co-authors also created a dynamic website that extends the book’s materials even further. It includes resources such as a glossary, maps, timelines, photo essays and a podcast “Medieval Art Matters,” where medieval art and architecture experts share their insights and expertise.

The mind as the main character

Paul Bloom, a professor in the Department of Psychology, is fascinated with developmental psychology, personality and how we make sense of the world, with a particular interest in pleasure, morality, religion, fiction and art.

His latest book, Psych: The Story of the Human Mind had its origins in the introductory psychology course Bloom taught at Yale University. It’s filled with anecdotes and intriguing facts that help explain psychological principles and bring them to life.

He tries to put forth the best answers available to the fundamental questions most have pondered: How does the brain give rise to intelligence and conscious experience? Where does knowledge come from? How and why do we differ in personality, intelligence and other traits? How does the mind of a child differ from that of an adult? And, what makes people happy?

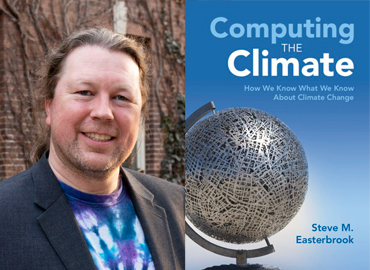

The validity of computer-generated climate models

Do computer programs or simulations that describe the Earth’s warming atmosphere work? How do we know we can trust the predictions about climate change they make?

Steve Easterbrook, the director of the School of the Environment and a professor in the Department of Computer Science describes his quest to answer these questions in his new book, Computing the Climate: How We Know What We Know About Climate Change.

Easterbrook visited climate change labs around the world and saw firsthand that climate models work very, very well. He found they show with remarkable accuracy how the atmosphere works over long periods.

Why are they incredibly trustworthy? According to Easterbrook, it’s because they’re the result of a rigorous global collaborative effort on the part of hundreds of scientists across many disciplines.

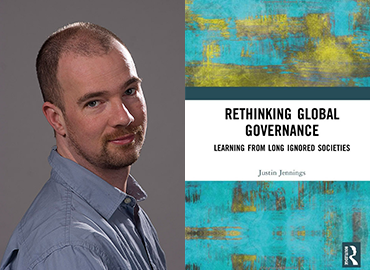

Ancient solutions to modern problems?

The world now grapples with many common horrors: climate change, pandemic disease, cybercrime and income inequality are among the biggest. For solutions, we often look to the United Nations, NATO, the World Bank or other international organizations designed to provide remedies.

But the world has changed dramatically since the creation of these institutions. Authoritarianism and nationalism are on the rise, making cooperation between nations more difficult. There’s growing economic friction between the West and the rising economies of the East.

Add to this the growing problems related to globalization, with its fluid flow of ideas and people across borders — both actual and digital. In view of all this, is it time to think about new ways to tackle global problems?

Justin Jennings, the curator of World Cultures at the Royal Ontario Museum and an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology thinks so. Researching different societies — some thousands of years old, others more recent — he has learned a great deal about their methods of resolving difficult issues and maintaining order. His new book, Rethinking Global Governance, argues that we can learn from them.

A moving (and funny) story of an immigrant biracial family

For author and A&S alum, Charlotte Gill, the COVID-19 pandemic gave her the time and space she needed to explore her family’s life as immigrants in her newest book.

Now an author and a writing instructor at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity and the University of King’s College in Halifax, Almost Brown: A Mixed-Race Family Memoir, was published in June 2023.

In it, she explores the story of her mixed-race, immigrant family, creating a deeply personal memoir with a contextualizing historical lens.

The story begins in the 1960s in London, England, where Gill’s English mother met her Indian father, in a time and place where their interracial love was far from welcome. The story follows her family’s life across the United States and Canada, as well as “all the tragic comedy of being an immigrant family as well as a mixed-race family.”

Exposing the (naked) truth in ancient Greek culture

For over a thousand years of Greek antiquity, athletes skilled in running, long jump, discus, javelin and other events trained and competed naked. They represented the ideal male body type and were regarded as citizens of a high socioeconomic status.

But why? What was so important about nudity that turned it into the respected standard for athletic pursuits? Sarah Murray, an assistant professor with the Department of Classics, seeks to uncover this mystery in her new book, Male Nudity in the Greek Iron Age.

She thinks some answers can be found through studying small bronze figurines that date from the final phase of the Bronze Age (1200–1050 BCE) and the first phases of the Iron Age (1050–700 BCE).