One summer day in 2022, a gold miner working in the Yukon came upon something even more valuable than what he was looking for: an almost perfectly preserved woolly mammoth, with skin and hair intact. The baby female calf was thought to have been resting in the permafrost for more than 30,000 years.

It was the biggest paleontological find in Canadian history, and the latest milestone in a great tradition. Since the 18th century, frozen woolly mammoth specimens (usually skeletons or bones) have been periodically found in diverse locations around the world. Links to an unfathomably distant past, they never fail to astonish us.

They have certainly captured the imagination of Rebecca Woods, an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of History. Her current research focuses on the place of frozen woolly mammoths in the global history of science — work that is being transformed by Alexander Offord, her research assistant and a PhD candidate at the Institute for the History & Philosophy of Science & Technology (IHPST.)

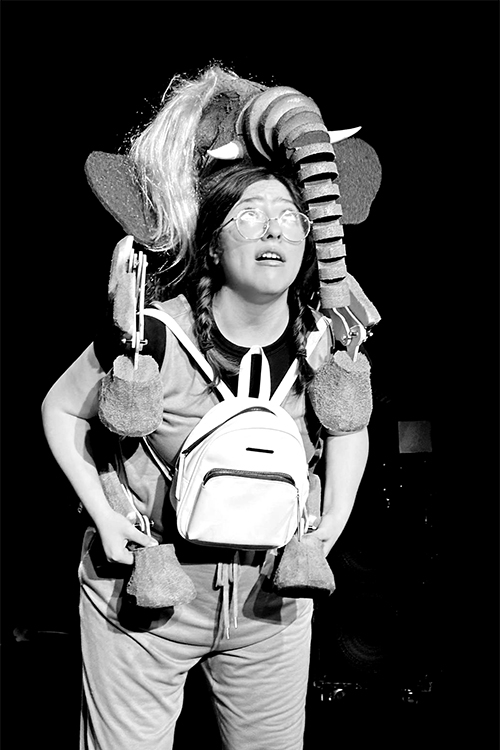

Alongside his academic career, Offord and his partner Nicole Wilson are the artistic directors of Toronto theatre company Good Old Neon. Their new children’s play is called The Last Mammoth, which sees a young girl and her mammoth puppet friend embarking on a journey to explore questions about climate change, extinction and environmental preservation.

Woods, who is herself cross-appointed to IHPST, first became interested in mammoths through her research on sheep.

“As a historian of science I find myself drawn to stories about animals, and the ways in which they can help us understand different historical processes,” she says. In her 2017 book The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900, she illustrated how farmers in Australia and New Zealand created sheep breeds to serve British meat markets.

In the early days of refrigeration, diners were mistrustful about eating meat that had been slaughtered six months previously — so vendors decided to allay their fears by pointing to the example of a famous woolly mammoth discovered earlier in the century in Siberia, which had been unearthed from ice and fed to dogs without harm.

“That story got me thinking about how the scientific and cultural meanings of mammoths have changed since that time,” says Woods. “For contemporary audiences, in a moment of great anxiety about global warming, frozen mammoths preserved by permafrost serve as a loud warning bell about a warming earth. It’s totally different than how they were first understood in the early 19th century.” Recent reports show that as the planet warms and permafrost melts, ever more mammoth discoveries are being made.

A requirement for one of Woods’s research grants was to show how her research could be used in schools. Offord was a natural help to her here, and so the idea for a children’s play was born.

“We’d never made theatre for young audiences before,” Offord says, admitting that the subject matter did not immediately lend itself to a production for kids. “A lot of children’s shows are very optimistic and shiny. And we said to ourselves, ‘how do we speak to some of the darkness that children will go through on this topic in a way that is respectful to them?’”

“I feel there’s an urgency to the project,” he continues. “The climate crisis is happening, mass species extinction is happening. And because it’s new, adults don’t really have the language to talk about it, let alone in a way that kids will understand. So it was necessary to create a piece that introduced these concepts to children so they could access them. And to do it in a way that was honest, but also fun.”

With funding from a SSHRC Partnership Engage Grant and sponsorship by the Jackman Humanities Institute, The Last Mammoth was first workshopped in early September for an audience of elementary school students and caregivers. The feedback they provided after the show will prove valuable as Offord’s company continues to develop the script.

Though in its early stages, the play offers ample proof that it’s not only possible, but necessary to translate academic research on serious issues that will affect future generations.

“To me it feels like an incredible honour,” says Woods. “What I appreciate so much about it is that a cross-generational audience from all walks of life can learn about my research — embodied in this incredibly evocative puppet, these gifted actors, and Alexander and Nicole, who’ve figured out how to make it all come alive. It’s a play that really gets at the emotional core of what’s at stake in the work that I do.”