“Pallasite meteorites are the most beautiful, most fascinating meteorites to have fallen to Earth,” says Corliss Kin I Sio, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Earth Sciences.

Pallasite meteorites contain eye-catching, amber-coloured crystals of the mineral olivine — the primary component of the outer shell, or mantle, of planets — embedded like gems in a matrix of iron and nickel.

For years, it was thought that this olivine-metal mix was formed deep within planetesimals — small planet-like objects from which planets formed — at the boundary between their metallic cores and outer, mineral mantles.

According to this theory, the impact of an asteroid blasted away the mantle, exposing the olivine-metal alloy and launching it into space. After travelling through the solar system, some of the debris eventually fell to Earth as pallasite meteorites.

But the origin of this olivine-metal mixture is not fully resolved with recent studies pointing to a different theory. Now, new research led by Sio and Neil Bennett, also an assistant professor in the Department of Earth Sciences, provides strong evidence for an alternate genesis.

What we’ve discovered means that all the explanations about the origin of pallasite meteorites in all those museums will have to be rewritten.

“Because they’re so beautiful, you see many pallasite meteors on display in museums with labels saying they were formed at the core-mantle boundary of planetesimals,” says Sio. “What we’ve discovered means that all the explanations about the origin of pallasite meteorites in all those museums will have to be rewritten.”

In a paper published in Geochemical Perspectives Letters, Bennett, Sio and their co-authors show that pallasite meteorites weren’t formed deep within a planetesimal early in its creation.

According to their research, pallasite meteorites were formed when a metallic asteroid fused with the mineral mantle of the planetesimal. The newly forged material was then scattered into space by subsequent collisions.

“The consensus is shifting towards these objects originating in impacts,” says Bennett. “And it's telling us just how commonplace these collisions are.”

The researchers reached this conclusion by analyzing pallasite meteorites from the collections of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) and the Smithsonian Institution, and by synthesizing olivine and metals in the lab to simulate pallasite forged at the core-mantle boundary of planetesimals.

When NASA visits Psyche, they could find an object that has gone through collisions to strip its mantle away. It would be exciting for us to see that it's actually a ball of metal.

The synthesized pallasites were created under conditions that mimicked the high temperatures that would have existed at the core-mantle boundary of forming planetesimals. These high temperatures — followed by a long cooling period — resulted in a state of equilibrium between isotopes in the olivine and metal, with a lower ratio of two iron isotopes in the metal compared to the ratio in the olivine.

In contrast, in the natural meteorites, the olivine and metal did not show the same equilibrium and showed a higher ratio of the same two iron isotopes in the metal compared to the ratio in the olivine.

This is what the researchers would expect from the lower temperatures and rapid cooling that would have occurred in an asteroid-planetesimal impact.

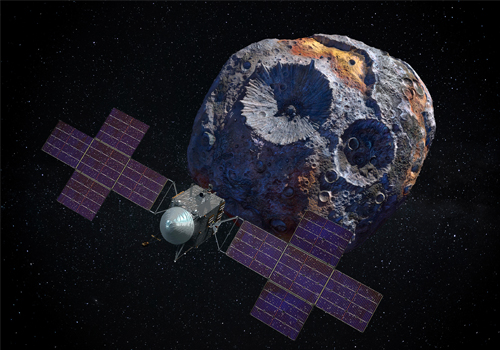

Because of their research, Bennett and Sio will have heightened interest in a NASA space mission being launched in 2023.

The target of the mission is the asteroid Psyche in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The endeavour is being described as a “mission to a metal world” because Psyche appears to be composed almost entirely of metals. That means it could be the core of an asteroid that had its mantle stripped long ago by a collision.

An asteroid like Psyche is just the type of object that would have spawned pallasite meteorites. During an impact into a planetesimal, its metal and the planetesimal’s mineral mantle would have fused to form pallasites.

“When NASA visits Psyche, they could find an object that has gone through collisions to strip its mantle away,” says Sio. “It would be exciting for us to see that it's actually a ball of metal.”

“It would certainly back up what we're saying,” says Bennett. “It should be fun to see.”