In June 1786, a 14-year-old boy lived in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, then the site of the largest population of free and enslaved Black people in Canada. Likely born in Maryland, Virginia, New England or New York, he would have been among the 1,500 Black individuals forcibly brought to the Maritimes by Loyalist enslavers at the end of the American Revolutionary War.

His name, once known but lost to time, is noted as “Name Unrecorded” in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (DCB). The entry is based on a local newspaper advertisement that listed him for sale as an enslaved person, with critical context from the author. It also raises many questions — who was his family? What were his hopes and dreams? And what happened to him?

The DCB features this story alongside those of five other enslaved Black people in the Maritimes. A joint project between the University of Toronto and Laval University, the DCB comprises authoritative biographical entries for over 9,000 individuals and continues to grow. These recent entries are part of a larger endeavour to present a more inclusive and accurate picture of the people who have shaped Canada’s history, a central tenet of the DCB since its first volume was published in 1966.

Its historians and editors have moved past the limits of a chronological approach, revisiting past biographies and creating new ones to account for the explosion of research in the last 30 years in the history of racial minorities, Indigenous history, women’s history, and working class and rural history.

It’s an exercise in rigorous detective work and truth-telling that the team doesn’t take lightly, says David Wilson, the general editor of the DCB and a professor with the Department of History and St. Michael’s College’s Celtic Studies program.

“We often read history against the grain — interpreting sources produced by those in power from the perspective of those who were subjected to that power,” says Wilson. “We approach all our sources with a skeptical eye and take care to verify each statement’s accuracy.

“For example, the Book of Negroes — a ledger compiled in 1783 of 3,000 Black people who were evacuated to British North America — is an important historical source. But it is also full of inaccuracies and needs to be treated with great caution.”

Since its first volume, DCB historians and editors have worked with limited fragments of surviving evidence to recreate the fullest possible picture of a person’s life, offering glimpses into personalities and personal experiences within the context of the times.

Take Diana Bestian’s story for instance, pieced together from her exceptionally thorough burial record that documents her enslavement, a likely non-consensual sexual encounter with a naval officer that left her “deluded and ruined,” and her unheeded attempts to get help from Cape Breton’s elite. As the DCB notes, one could infer from this level of detail that the burial record’s author identified with Bestian’s plight.

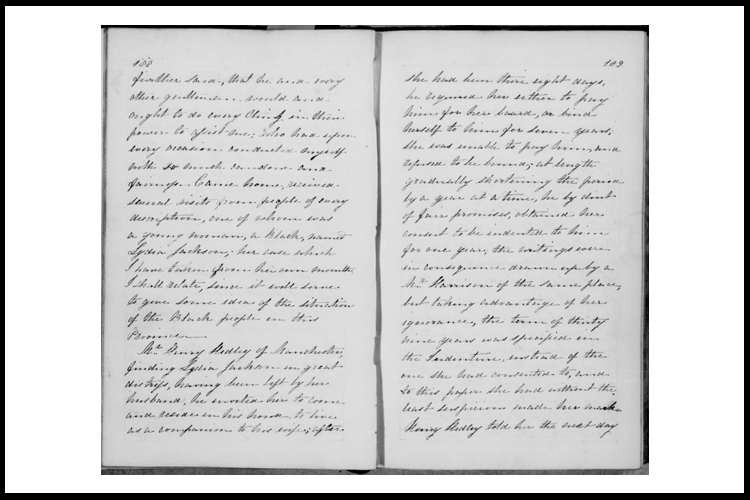

In another example, Lydia Jackson’s existence is known only because a lieutenant active in the abolitionist movement recorded her story in his diary. Jackson seems to have arrived in Nova Scotia as a free Black woman before being wrongfully re-enslaved. She eventually escaped, fleeing first to Halifax, and likely leaving for Sierra Leone with 1,200 other Black Loyalists.

Next year, the DCB will publish seven more biographies of enslaved Black people brought to Upper Canada (now Ontario) by their enslavers.

The project is also turning its focus to Indigenous, female and rural lives that are underrepresented in the historical record. For instance, while agriculture was the principal occupation in Canada up to the 1920s, historians have found it challenging to understand the lives of those who worked in farming.

Accessing source material for women has also been difficult. Wilson notes that while the lives of nuns in New France are well-documented, most women in Canada from the 18th to early 20th century are not. “Fortunately, some rural women kept diaries. These diaries not only documented crop rotations and weather conditions but also community interactions, tensions and their religious lives.”

Digitizing archives has unlocked new opportunities for historians to explore these previously overlooked and erased aspects of history, says Wilson.

“Thanks to historians from institutions around the country, donations from the general public, and the financial support of the Museum of Canadian History and the Department of Canadian Heritage, the DCB can continue to revive important stories – allowing readers to form their own judgments and ensuring that the complex histories of all Canadians are recognized and remembered.”