As director of the Tayinat archaeological project in Turkey, Tim Harrison saw the need and potential for 3D scanning and modelling technology.

Harrison, chair of the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Near & Middle Eastern Civilizations, has for years conducted research in the region of the Orontes River which flows from Lebanon through Syria and Turkey. Populated continuously for thousands of years, the region’s rich history is reflected in a wealth of archaeological finds.

However, archaeological finds are rarely uncovered in pristine condition and whole.

“We’ve found thousands of fragments of broken sculptures,” says Harrison. “It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, but it’s a three-dimensional puzzle and you only have maybe five per cent of the pieces.

“So, we became very interested in the development of fast, high-resolution scanning technology that would help generate 3D images that we hope to eventually import into shape-matching software that will help solve these puzzles.”

The 3D scanning and modelling that Harrison and his colleagues are doing is accomplished using portable, hand-held scanners that can be used in the field. They are also developing shape-matching software with a team led by Eugene Fiume, a professor emeritus in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Computer Science.

One goal is to be able to create 3D models of pieces of pottery or statues and rebuild them digitally the way you manually rebuild a broken coffee cup by fitting its pieces together. Another is to identify artifacts such as pieces of pottery by comparing their shape to a database of similar pieces.

“Eventually, we also want to compare texture, color, chemistry and minerology,” says Harrison. “The more layers of information you add, the more patterns and matches you can make. We're not quite there yet, but that’s the direction we’re headed.”

According to Steve Batiuk, a senior research associate in the Department of Near & Middle Eastern Civilizations and a member of the Tayinat team, “3D modeling quite literally introduces a new dimension to our research, providing us with new ways to measure objects, visualize them and help in reconstruction.

“Plus, since many of these artifacts can’t leave the countries from which they were excavated, it extends our ability to do research on them beyond the field season and allows others who were not there to work on them as well.”

As powerful as it is, the 3D scanning capability is just one tool in the toolkit that Harrison and his colleagues launched in 2011 called the Computational Research on the Ancient Near East or CRANE.

With funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), CRANE was originally conceived as an effort to build a large collaborative environment for different archaeological projects and researchers working mostly in the eastern Mediterranean. At its core are powerful computational tools for modelling ancient social groups, analyzing complex and diverse data sets from those researchers — and it will even be used to validate climate change models with archaeological data.

The 3D capability is part of what Harrison refers to as “CRANE 2.0” which was made possible through a partnership grant — that includes funding from SSHRC and the Faculty of Arts & Science — to equip the Archaeology Centre’s Digital Innovation Lab. With this Faculty support, researchers in other departments can apply this technology to their own realm of the ancient world.

The application of 3D scanning to create models of architectural complexes and artifacts has revolutionized our research. It permits continued, detailed analysis long after the close of excavations and on-site laboratory analysis.

“The technology was purchased by CRANE for CRANE work,” says Batiuk. “But all archaeologists at U of T can benefit from us having bolstered the Digital Innovation Lab. This is a spirit of cooperation that CRANE is trying to promote, especially when using University funds.”

Ed Swenson is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and director of the University’s Archaeology Centre. Last winter, Swenson, his former doctoral student Giles Spence Morrow — who is now with the anthropology department of Vanderbilt University — and other colleagues conducted research at ancient sites from the Angkorian Empire that was based in present-day Cambodia and dominated much of Southeast Asia. The work was supported by a grant from the Hal Jackman Foundation.

The team surveyed and conducted excavations of religious temples and complexes built near the end of the first millennium CE. They employed traditional archaeological methods and tools in their work, as well as drone cameras. They also used CRANE’s portable scanners to create 3D models of statues, stone monuments and architecture, and to record inscriptions to facilitate translation and share with other researchers.

One of their most remarkable discoveries was of pieces of a statue that was likely a three-metre-tall likeness of a divine figure. The team discovered a base on which were two feet. Nearby they found a shoulder, an arm, part of a leg and the torso. The head was not found.

The team scanned the pieces and re-assembled both the actual statue and its digital facsimile.

“The application of 3D scanning to create models of architectural complexes and artifacts has revolutionized our research,” says Swenson. “It permits continued, detailed analysis long after the close of excavations and on-site laboratory analysis.

“In other words, one can literally revisit and restudy sites that are accurately recreated in 3-dimensional simulations. The models also offer an invaluable teaching resource as it allows students to fully experience and analyze virtual archaeological datasets.”

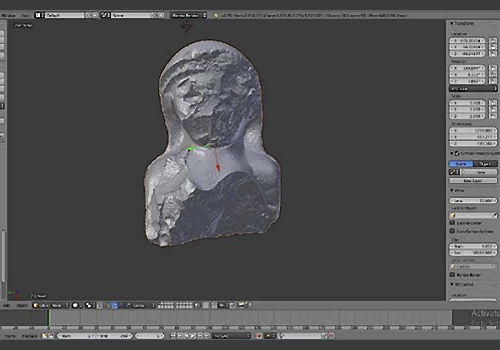

A 3D model of a reconstructed torso of a statue. Courtesy of Yaśodharāśramas Archaeological Project; Giles Spence Morrow.

Bence Viola is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology. As a paleoanthropologist, he studies the interactions and relationships between different sub-species of humans living during the late Pleistocene epoch which ended nearly 12,000 years ago.

Using the 3D scanning capability of CRANE, Viola creates 3D models of the teeth of Neanderthals, an extinct species of humans who — until around 40,000 years ago — lived alongside our human ancestors in what is now Eurasia. The scans serve as documentation and are used in analyzing the specimens. They also aid in the producing illustrations and enable the creation of 3D-printed replicas.

Klara Komza, one of Viola’s PhD students, is researching the evolution of feet and has scanned some 5,000 ape and human foot bones from about 400 individual feet. Komza’s goal for 2020 was to scan the entire fossil record of the earliest hominins — the first of our human ancestors to stand and walk on two feet who lived between five and one-and-a-half million years ago. That project would have taken her to Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa this past summer, but that effort was halted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the pandemic has curtailed some research activities, it has also revealed new value in turning objects into digital facsimiles.

“Along with colleagues at U of T Mississauga,” says Viola, “we’re scanning several skeletons from our teaching collection and creating digital replicas which we’ll use in virtual labs for online classes in the fall.”

Batiuk and his team are partnering with the Gardiner Museum to do the same for museum goers whose access to the museum’s collection has been similarly restricted by the pandemic.

They have begun scanning Japanese ceramic pieces and South American artifacts from the Gardiner’s collection which the museum plans to exhibit online. Not only will the public be able to view pieces from the collection, they’ll be able to interactively “handle” them in a way they couldn’t in a gallery.

“This technology allows people to explore an object in multiple dimensions, almost as if it were in their hands,” says Batiuk. “From a public outreach standpoint, it brings the material to life and engages the audience in ways that still photographs never could.”