In the 1960s, psychiatrists and psychologists believed autism was caused by unloving mothers — their lack of affection and caring pushed children into this condition.

Clara Park, a Massachusetts writer and homemaker whose three-year-old daughter, Jessica, was diagnosed with autism, was accused of being responsible for her disability. She was labelled a “refrigerator mother” — a cold, intellectual parent starving Jessica of the natural affection she needed to develop properly.

But having already raised three kids, Clara refused to accept this. Though she had no scientific training, she set out to challenge and enhance the scientific community’s understanding of autism and give other parents of autistic children a greater voice.

“She was the first mother who dared to tell the experts, ‘there is no way my child is autistic because I don't love her,’” says Marga Vicedo, a professor in Faculty of Arts & Science’s Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science & Technology.

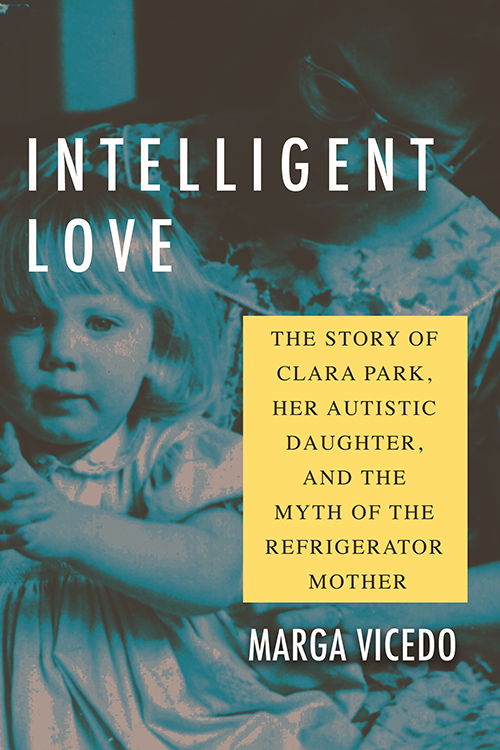

Vicedo explores Park’s courageous life and work in her new book Intelligent Love: The Story of Clara Park, Her Autistic Daughter and the Myth of the Refrigerator Mother.

“I wanted to show that relationship of how science influences people, and how people also become agents in shaping the direction of science,” says Vicedo, who describes the book as part history of science and medicine, part biography.

Taking well over a decade to complete, Vicedo researched family archives, the archives of major researchers on autism, conducted in-person interviews and studied Park’s book, The Siege — a 1967 memoir about her daughter’s behaviour and development — and the family’s engagement with her.

“I was fascinated by this book,” says Vicedo. “Clara was an incredible observer who took a huge amount of notes. Her grasp of autism and human nature was ahead of her time. When this book was published, it was the most detailed account of the first eight years of an autistic child.”

Vicedo admits to being a little nervous when interviewing Clara Park, though they already shared a connection. In a twist of fate, one of Park’s other children, Harvard’s historian of medicine Katherine Park, happened to be one of Vicedo’s professors in graduate school.

“I was so intimidated by Clara’s presence,” says Vicedo. “She was a very articulate speaker and writer, but she was also incredibly kind and nice.”

That kindness was paired with a fierce determination to have scientists see the value of experiential knowledge in medicine and acknowledge the importance of collaboration between medical experts and the parents of autistic children.

She didn't reject scientific knowledge, stresses Vicedo. But she firmly believed that parents’ experiences should be recognized as legitimate source of expertise, and that their intimate knowledge of their children’s behaviour was an untapped source for understanding autism.

But this was a monumental shift. And she received her fair share of criticism.

That's why I called the book Intelligent Love. In combining intelligence and love, she was also calling for a different view of motherhood, because mothers were supposed to love only instinctively, naturally.

“It was revolutionary at the time because the understanding of science was that to be objective, scientists could not be emotionally involved, they had to be completely detached,” says Vicedo. “But Clara Park believed the fact that she had a subjective point of view because she was talking about her daughter did not make it illegitimate.”

In fact, not only was Park challenging scientific research, she offered a reevaluation of parenting.

“Clara claimed, ‘intelligence and love are not natural enemies,’” says Vicedo. “That's why I called the book Intelligent Love. In combining intelligence and love, she was also calling for a different view of motherhood, because mothers were supposed to love only instinctively, naturally.”

Maternal love could be intelligent, Park argued. Her detailed analysis of Jessica’s condition and her systematic gathering of information only reflected her wanting to better understand and connect with her daughter.

Through her book and other writings, Park also became an activist fighting for education and support for autistic people. Through her efforts, parents came together and became “a very strong force in the autistic community to challenge many of the ideas and to advocate for services and education for autistic children,” says Vicedo. “They formed organizations, met with scientists, developed conferences.”

There are still numerous controversies in the autistic community, about different ways of understanding autism. And I think what Clara had to say is still relevant today.

Clara Park passed away in 2010, and Vicedo and Jessica remain friends to this day. Jessica, now in her early 60s, lives in the same Willamstown, Massachusetts home where she grew up. She works at nearby Williams College, and is supported by siblings and her community. She has also become an accomplished artist whose paintings have been shown at several galleries and exhibitions across the U.S.

Though much has changed since the 1960s, Vicedo still believes there’s room for even more positive change.

“There are still numerous controversies in the autistic community, about different ways of understanding autism,” says Vicedo. “And I think what Clara had to say is still relevant today.”

She hopes Intelligent Love sparks new conversations about “what kind of science we want and how we can be more inclusive of different voices,” says Vicedo.

“Science is such a big part of our lives,” she adds, noting the current COVID-19 pandemic being a prime example of this.

“We have to become more conversant and more knowledgeable about what science is and how it affects our world. So let’s have the conversations that we need about our role in supporting people with disabilities, for example, encouraging different viewpoints. That will lead us to better science and a better society.”