Most people are familiar with the African American revolutionary, Muslim minister and human rights activist, Malcolm X, but far fewer are aware of the history and legacy of his mother, Louise Langdon.

Erik. S. McDuffie believes this courageous woman embodies Black resistance, resilience and freedom in the American Midwest.

McDuffie, an associate professor with the Department of African American Studies and History at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, gave the Faculty of Arts & Science’s annual Black History Month lecture on the St. George campus, hosted by the Department of History last month.

His address titled, “Louise Langdon, Garveyism, and the Transformative Power of Black Canadian History in a Moment of Global Crisis” focused on his latest book, The Second Battle for Africa, Garveyism, the US Heartland, and Global Black Freedom.

Garveyism refers to the 1914 movement created by Marcus Garvey — a Jamaican-born Black nationalist who established a doctrine that advocated for Black self-governance, racial pride and Pan-African unity.

“My book rethinks prevailing narratives of the African diaspora, African American history, the U.S. Midwest, Garveyism and global Africa by calling attention to the importance of the U.S. heartland in shaping 20th century global Black history,” said McDuffie.

“Through the life, the legacy, the diaspora journeys and migrations of Louise Langdon, and the transformative power of Black history, particularly Black women, working class, queer, trans and everyday women have been at the front lines and are not only challenging the multiple oppressions they face, but imagining another world is possible.”

McDuffie reflected on his own Midwest African American heritage and his connection to north of the border.

“Being up here in Canada, especially in Toronto, is very important to me,” he said, noting that his great grandmother migrated to Toronto from the island of St. Kitts before his family settled in the United States.

“I’m a sixth-generation African American Midwesterner. My family has lived in the U.S. Midwest since the 1830s. However, like all Black people, one of the things I'm trying to do in this book is understand that African Americans are a diasporic people.”

As he continues his research, he praised Canadian scholars and students who are researching Black Canadian history with the same passion.

“Scholars in Canada, especially of African descent, are at the front lines in producing cutting-edge scholarship in multiple fields — Black Canadian history, African diaspora studies, Black women studies, Black queer studies and other fields.

“This work has moved Canada from the margins to the centre of discussions of global Africa. The scholarship is rethinking commonly held assumptions about slavery, memory, citizenship, state violence, sexualities, indigeneity, settler colonialism, migration, borders, culture, resistance, diaspora and the meaning of freedom.”

Returning state-side, McDuffie explained how cities like Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland, as well as rural areas in the U.S. heartland, became central incubators of Garveyism which included the creation of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

By 1920, the association had over 1,900 divisions in more than 40 countries, including 5,000 members in 32 divisions across Canada. McDuffie showed the audience a photo he took in 2022 of 355 College Street — just blocks away from campus — which is currently an empty lot.

“That was the site of the old Toronto UNIA and Garvey held two regional conferences in 1936 and ‘37 at that building,” he said adding, “I understand Garveyism as the most political, most potent political social, cultural and religious force in the 20th century Black world.”

One Garvey follower was Louise Langdon, known in the U.S. as Louise Little.

Born in Grenada from parents originally from Nigeria, Langdon left the Caribbean in 1917 because of a lack of opportunities for young Afro-Caribbean women. As a teenager, she migrated to Montreal, and it was there she became a Garveyite and joined the UNIA.

“Louise grew up in a family that was deeply proud, that valued self-reliance and education,” said McDuffie. “She spoke French, Creole and English. And although she spent only two years in Montreal, those two years were foundational in cultivating her Black radical internationalism that she would pass along to her children.”

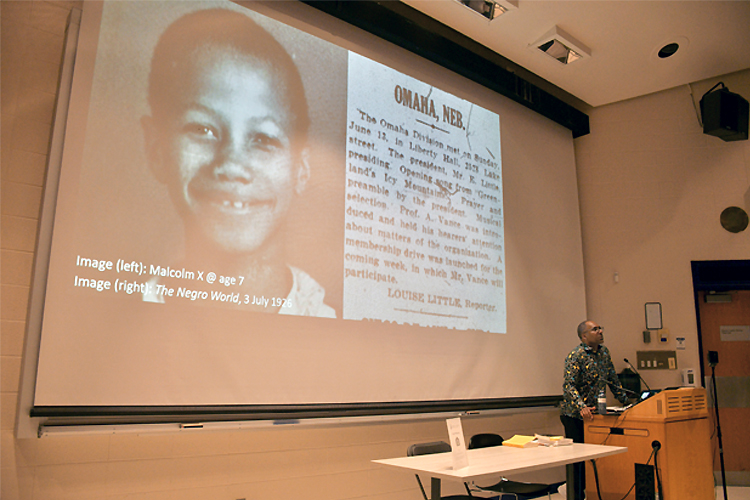

It was also in Montreal that she married Earl Little, a fellow Garveyite with whom she had eight children, including Malcolm Little who changed his name to Malcolm X in 1952 to signify the loss of his African ancestral surname.

The couple moved from Montreal to Philadelphia, and then to Omaha, where they raised their family and Langdon became the secretary and the branch reporter of the UNIA's local chapter, sharing news about local UNIA activities.

In 1931, Earl Little died mysteriously, quite possibly a victim of racial violence. Langdon was left to raise eight children on her own during the height of the Great Depression “where approximately 50 per cent of Black Americans were unemployed across the country,” noted McDuffie.

By the late 1930s, the stress of taking care of so many children as a widow amid a crumbling economy had taken their toll. Her behaviour became erratic and disconcerting. “She may have been suffering from postpartum depression,” said McDuffie.

Living with her family in Michigan, Langdon was committed by the state. Here, McDuffie problematized the context of Langdon’s committal under the context of racial and gender-based surveillance and violence.

“They put her into the Kalamazoo Psychiatric Hospital in 1939,” said McDuffie. “She spent 25 years of her life there, from her early 40s all the way to her 60s.” One of Langdon’s daughters, Yvonne, fought and struggled for years to have her mother released, finally succeeding in 1963.

“One of the key points of my book is that I argue that we need to understand Louise’s ordeal as a form of state violence and understand that Louise Langdon was a political prisoner,” said McDuffie.

She lived for almost 30 years after her release, reconnecting with her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren, passing away in 1989.

Today, she is still admired as a symbol of resilience.

“In recent years, Black queer feminists in Montreal have been at the forefront in remembering and celebrating the life and legacy of Louise Langdon, most notably through the Black queer feminist organization Third Eye Collective, comprising Black women from Canada, the Caribbean, Europe and Africa who are dedicated to healing from and organizing against sexual and state violence,” said McDuffie.

McDuffie quoted Délice Mugabo, a Third Eye Collective member and an assistant professor of feminist and gender studies at the University of Ottawa, who wrote: “(Louise’s) vision insists that we continue to create and nurture Black worlds that can imagine and bring forth Black freedom. Louise Langdon taught us to not wait for it, but to make it.”

“There are so many scholars, as well as everyday people, who are thinking about recovering and celebrating the transformative power of Louise Langdon,” said McDuffie.

“I want to emphasize that she was not a victim. She was a survivor. Her life, legacy and memory are more important now than ever, when we are truly at a moment of fascism, particularly in the United States.”