For University of Toronto historian Anna Shternshis, understanding the past means connecting with people’s stories — or, in the case of her research, their songs.

Shternshis, director of the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies and the Al and Malka Green Professor of Yiddish Studies in the Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures in the Faculty of Arts & Science, examines Jewish culture in Russia and the Soviet Union through oral history and Yiddish culture, music and theatre.

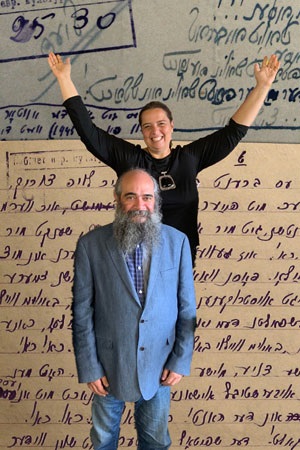

Her 2018 project Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of WWII, highlights forgotten Yiddish music written during the Holocaust in the former Soviet Union. Shternshis collaborated with Russian songwriter and performer Psoy Korolenko to contextualize archival material, bringing together a global ensemble of musicians to produce a Grammy Award-nominated album. The resulting songs reveal how Jews fought against fascism, tried against all odds to save their families and expressed themselves through music.

Shternshis, who serves as special adviser on community engagement to the dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science, has continued this work, most recently collaborating with the BBC for a radio documentary exploring the long-lost wartime songs of survivors who escaped the Holocaust by fleeing to Central Asia.

She spoke to Josslyn Johnstone at the Faculty of Arts & Science and Tabassum Siddiqui at U of T News prior to the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust about how survivors’ stories still resonate today.

How does International Holocaust Remembrance Day help us better understand history — and learn from the past?

Having one day of the year when we talk about an issue is not enough, but I think it’s important to have that time when we’re reminded to think about what happens to a group of people, often a minority. if they're not protected by law and by society's understanding of justice. At least there is one day when we talk about what happened to Jews in Europe — and it’s especially important in the context of university education because this is our chance to rigorously address the issue with our community of students and faculty. If not us, then who else could talk about this in a way that’s relevant? It’s important and it offers a chance to see the complexity of history by putting vulnerable individuals front and centre.

What are you trying to learn and convey about Jewish history through your research?

I’m studying how people experienced violence during the Second World War, and how they made sense of it during the war itself. I’m looking at the songs they created to document what was going on and express what they were feeling. Specifically, I’m interested in the history of the Holocaust in the Soviet Union and my focus is on people who rarely get to tell that story in their own voice. For many, music was the only way to document what was going on with them — and to leave a message for the future, which many of them did not expect to see

What have survivors told you about why music was a vehicle for expressing what they had been through?

In the archives that they found in Kyiv years ago, there were no stories — just songs. Survivors were terrified of telling those stories right after the war because the Soviet governmen ttreated anyone who survived the war and German occupation with suspicion, especially Jews. Survivors who had lived through hell were now afraid to go to jail for surviving. The only thing they could do was to sing because authorship of a song was not immediately attributed to them — they could just say they heard it somewhere. So, they told that story through music. History and memory are not always telling the same story.

Have you found common threads within the music they created?

In these songs, there are a lot of calls for justice; there’s also a lot of humour — they’re making fun of things that terrify us, like death or starvation. There was a sense that a lot of the people who were writing these songs would not see tomorrow. Many of these sentiments become less relevant after the war — and that’s why these songs are almost always forgotten, because people begin to worry about other things. But they give us a sense of what mattered to people there at that time.

You’re continuing your research into the songs of Holocaust survivors by looking at what happened in Central Asia during the war. Why is that region significant?

This past fall, I went to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan with BBC Radio producer Michael Rossi — who had done a story a few years ago on my previous work — and British singer Alice Zawadzki, whose family were Polish citizens in Kazakhstan during the war. We wanted to explore the angle of those Muslim lands rescuing Jews during the Holocaust. So, she was tracing her grandmother and I was tracing the songs. And when we got there, she sang some of those songs and some of the local musicians performed with her as well. We used photographs from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., to see where people had gone during that time. The story is incredible — 1.4 million Soviet Jews and around 250,000 Polish Jews survived the war there. And there are a lot of descendants of those people living in Toronto today.

But when we got there, one of the takeaways for me was how the memory and knowledge of that story was just not there. We thought it would be a source of pride — that history of saving all these refugees. But because there are almost no Jews left in the region, the story is just gone. So, it felt really special to bring the songs there and sing them to remind ourselves that just because history is forgotten doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen. And in today’s world, where so many refugees are fleeing and countries are once again arguing about whether they should welcome people, it was important to go there and remember how these small countries with no resources still rescued all these Jewish families that were not welcome anywhere else in the world.

Why is doing this work important to you?

I teach diaspora studies and the students and I often discuss what it’s like to be asked the question, “Where are you from?” This question rarely comes out of curiosity, but most often out of the need to assert difference or even a distrust. My research draws attention to experiences of violence among people who are “not from here,” or treated as strangers even in their own land. It is challenging to look at people as people, as opposed to just talking about numbers, processes and resources, but I argue that such an approach is crucial for understanding both the past and the present. My work is clearly connected to my personal family history as well — through my journeys, I got a little closer to understanding what my ancestors went through.

How can telling the stories of survivors help create a more equitable and inclusive society?

I think a lot about that. Racism often comes from a point of view of fear — and it’s hard to be afraid of someone who you’ve met and had a conversation with, or to see that person as a source of potential danger. Almost all mass violence happens preventively: “We’re going to kill those people so that they don’t kill us.” It’s much harder to believe those kinds of statements if you actually begin to understand the other person. Obviously, my work does not have direct policy implications, but I do think in-depth learning of those refugee experiences really helps, including talking about the history of the Holocaust and antisemitism.