From turning points in pre-Nazi Germany and the rise of eugenics in Bolshevik Russia, to traces of libel and sedition in 18th-century British literature, three promising humanities projects at the University of Toronto are getting a boost from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

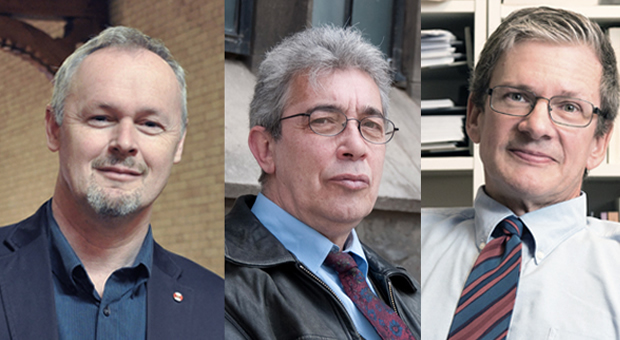

James Retallack of the Department of History, Nikolai Krementsov of the Institute for the History & Philosophy of Science & Technology, and Thomas Keymer of the Department of English were among 175 scholars, artists and scientists from across the United States and Canada recently named fellows of the foundation, chosen from over 3,100 applicants. Acknowledging their prior achievements together with the potential of their current projects, the award allows the three scholars to spend time focused solely on their research.

A missed opportunity for pre-Nazi Germany

For Retallack, that means the opportunity to research and write “The Workers’ Emperor”: August Bebel’s Struggle for Social Justice and Democratic Reform in Germany and the World, 1840-1913. A biography of the leader of the Social Democratic Party in pre-World War One Germany, the book will give the world a life-and-times account of Germany’s missed opportunities to implement liberalism and democracy and steer away from Nazism.

Retallack, who also recently received a Killam Fellowship from the Canada Council for the Arts, is a renowned expert on German society and politics between the Napoleonic era and the rise of Hitler. His study of Bebel will explore how Germans from different social and ideological milieus distinguished between routine opposition, civil disobedience, and “political terrorism” in a modernizing world.

“The division of political society in Germany before 1914 in many ways separated socialists from everyone else,” said Retallack. “Several issues that drew Bebel’s attention – the rights of women, abuse of aboriginal peoples, discrimination against Jews, fair elections, state surveillance – resonate today in Canadian public discourse. My aim is to illuminate the historical dynamics and uncertain outcomes that arise from the clash of political systems and charismatic individuals.”

Examining science and society in Bolshevik Russia

Krementsov’s project is titled “I Want a Baby”: The History of Bolshevik Eugenics. The word “eugenics” is most often associated with the genocidal race-purification programs in Nazi Germany and the coerced sterilization of “undesirables” in the United States and Scandinavia. However, the actual history of eugenics in Bolshevik Russia reveals that it was not based on coercion and a desire to maximize the genetic fitness of the Russian people.

The eugenics movement developed rapidly throughout Europe, Asia and the Americas in the early years of the 20th century but failed to secure legislative support or spark an organized movement in Russia. The situation changed radically after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution when, in just a few years, eugenics became an established scientific discipline, exerting influence on social policies and inspiring a sizable grassroots following. Then, just as suddenly as it began, eugenics was banned in the Soviet Union in 1930 under Joseph Stalin.

“Why did eugenics fail to develop in Imperial Russia but flourish under the Bolsheviks, only to come to a screeching halt a decade later,” said Krementsov. “My goal is to examine this history in detail in its national and international contexts. Public discourse and state policies towards science often change when a state’s leadership changes, so drawing lessons from the Bolshevik Russia period may offer insights into the relationships between science and society that many nations grapple with today.”

Skirting censorship in 18th-century British literature

Keymer’s interest in libel and censorship in literature grew out of his interest in the literature of the 17th and 18th centuries as periods of political upheaval. The Civil War and Jacobite Rebellions in Britain, and later the American and French Revolutions, each had an impact on determining the boundaries of acceptable communication.

Print was the most powerful medium for sharing ideas, and authorities went to great lengths to silence writers, with repressive laws, intimidation, and proxy arrests. Keymer is at work on a book about the interplay between official press control and politically inflected literature of the period titled Poetics of the Pillory: Literature and Seditious Libel, 1660-1820. The book will expand significantly on a string of public lectures delivered by Keymer at Oxford University last fall, to be published by Oxford University Press in the Clarendon Lectures in English series.

“There is so much to discover and explain about the distinctive features of 18th-century writing,” Keymer said, citing irony, ambiguity and innuendo as examples. “Authors dreamed up complex modes of expression to circumvent the constraints forced upon them at the time. It became all about how to write ingeniously.”

“These techniques remain crucial into our own time, too, in a range of repressive or coercive situations,” Keymer added. “George Orwell used them. You could even say that when Ai Weiwei was jailed or when the Charlie Hebdo satirists were killed, it was because they didn’t use them.”