If you’ve ever tried to work or study in an open-concept space, you probably faced some “acoustic challenges,” as Assistant Professor Joseph Clarke of the Department of Art History puts it.

But you also probably benefited from the free flow of information and movement in these kinds of spaces; perhaps you overheard a useful tidbit of chatter or slid your chair over to someone to ask a question or think through a problem.

This and related topics were explored by U of T scholars and international visitors from a range of disciplines — architecture, media studies, art history, literature and information studies — at a recent workshop, “Building Communication: Architectural History and Media Archaeology,” hosted by Clarke on behalf of the Department of Art History and taking place at the McLuhan Centre for Culture and Technology.

Clarke conceived of and organized this event with the support of a Connaught New Researcher Award. “One thing that sets our department apart among North American art history programs is our expertise in the history of architecture,” says Clarke. “I’m eager to showcase how we are embracing innovative methods in architectural history.”

In particular, talks at the workshop focused on spaces that house the work of communication, such as TV and radio stations, universities, libraries and offices.

How do these spaces facilitate or hinder the flow of people, work, sounds, messages and technologies? What effect do their materials, aesthetics and approaches to design have on these flows? And what makes up the larger systems these places are part of — roads, parking lots, empty tracts of land, cities, transit hubs, telecommunications cables?

The “Action Office”: acoustic communication makes waves in office design

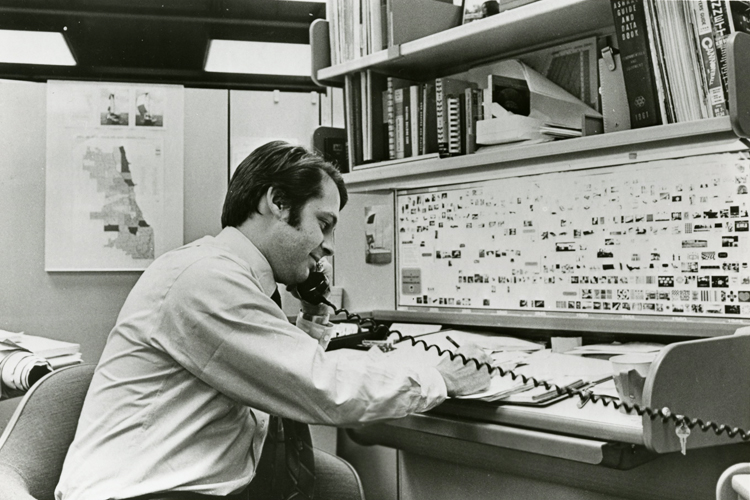

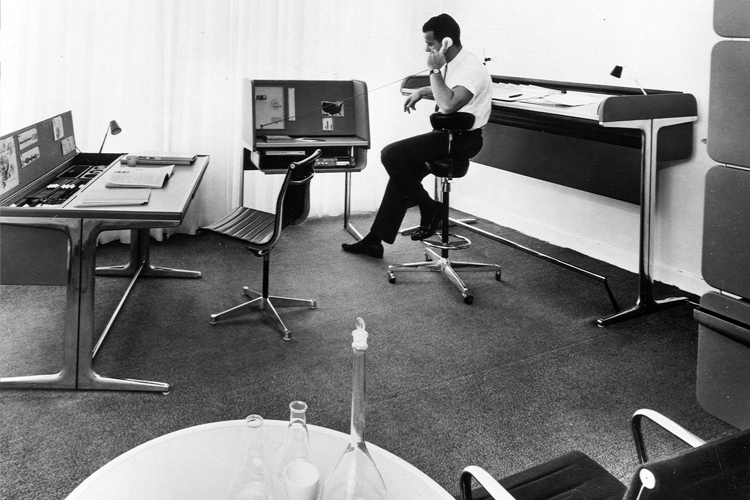

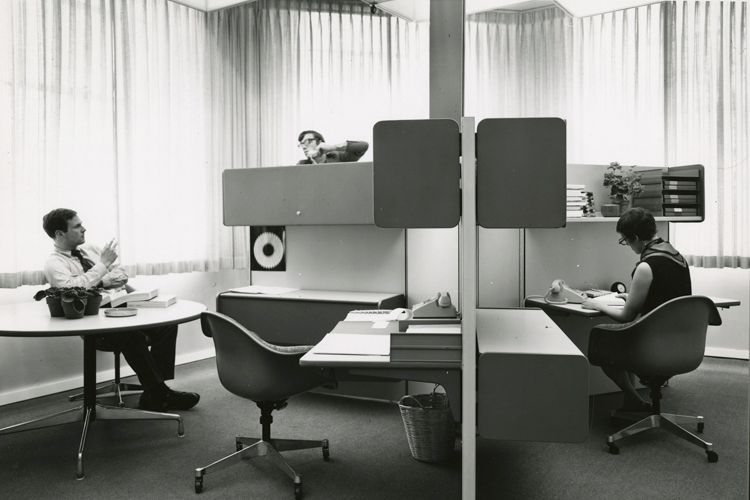

Clarke presented his current research on the mid-20th century open office design movement, such as the “Action Office” concept introduced by furniture company Herman Miller in the late 1960s, and the work of Wolfgang and Eberhard Schnelle — two brothers who championed an ostensibly human-centric office design that rejected the conventional arrangement of rigid rows of desks.

It was thought that these office spaces — open and malleable — would facilitate collaboration and the flow of information while also challenging the class and gender hierarchies of the corporate environment. But the space presented acoustic challenges, necessitating the use of carpeting, drop ceilings, drapes, quiet music, white noise generators and fabric-covered partitions to direct and minimize sound.

The “sonic exchange of information” was especially valued as a design factor when open-plan workspaces were being developed, says Clarke. He highlighted a quirky but topical remark that famed media theorist Marshall McLuhan made in 1967: “we are simply not equipped with ear lids!”

While the high modernism of the late 1960s was enthusiastic about revolutionizing office spaces, the development of computers and the increasing scarcity of office space in the 1970s and beyond meant that the dream eventually died. The cubicles we are familiar with today bear little resemblance to the dynamic and innovative “Action Office.”

The Potteries Thinkbelt: a mobile university on an abandoned railway line

Among other projects presented at the workshop, architectural historian Mary Louise Lobsinger, an associate professor in the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design who is also cross-appointed to the Department of Art History, spoke about her research into a curious tale from the 1960s: the Potteries Thinkbelt.

An ambitious and unconventional approach to making education more accessible and inclusive than ever before, the Thinkbelt was a large-scale system of infrastructure and communications technology intended to create a kind of distributed, mobile university on an abandoned railway line in Staffordshire, UK. Designer Cedric Price held a firm belief in the potential of technology and architecture to open education up to a larger sector of the population — including unemployed industrial workers who sought re-training after the closure of factories in the area — thereby stimulating economic redevelopment.

Price dreamed the Thinkbelt would facilitate participatory and self-paced styles of learning, something which we’ve achieved to some extent today with online and distance education.

But the Thinkbelt would never come to be: the 1970s saw the arrival of an era that reduced support for the public sector and dismantled social-democratic principles of education as a public good. The type of “systems thinking” that Price was doing was dismissed as mere “technocratic hubris,” an overconfident dream that technology could lead us to social emancipation.

Despite its ambition, Lobsinger criticizes one particular point about the Thinkbelt: “There are human beings moving through these systems,” she says. “How do people navigate through them and make sense spatially?” Projects like Price’s were “really oblivious to bodies,” says Lobsinger.

So, the next time you find yourself in an office or classroom, look around: what information can you transmit or receive? How does the space facilitate or hinder your learning, your collaboration with others, your ability to think?

Lessons from the architectural dreams of the past continue to inform the ways in which we organize ourselves into space meant for communicating with each other.