A new University of Toronto building at 90 Queen’s Park Crescent will bring together academic and public spaces to create a hub for urban and cultural engagement.

The nine-storey building will be designed by world-renowned architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the firm behind New York City’s High Line and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. The New York-based firm is working with Toronto’s architectsAlliance. ERA Architects is serving as the team’s heritage consultants.

“This stunning architectural landmark will provide the University of Toronto with an invaluable opportunity to create a meeting space for scholars and the wider city around us,” says U of T President Meric Gertler.

“It also gives the School of Cities a permanent home for its urban-focused research, educational and outreach initiatives.”

In addition to the School of Cities, the building will house a number of academic units from the Faculty of Arts & Science, including history, Near and Middle Eastern civilizations, as well as the Institute of Islamic Studies, an arm of the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies and the Archeology Centre. It will also provide facilities for the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Music.

There will also be space designated for classrooms and public spaces, as well as for the Royal Ontario Museum.

“It will be a building that brings a diverse grouping of folks together to advance knowledge around cities and how they can work successfully, contributing to a positive impact here in the city but also more globally,” says Scott Mabury, U of T’s vice-president, operations and real estate partnerships.

As design architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro will draw on their experience designing cultural and academic spaces to create a building that will inevitably become a Toronto landmark, says Gilbert Delgado, U of T’s chief of university planning, design and construction.

“They’re very provocative and thoughtful architects,” he says. “This dramatic building expresses the very special role of the university within the city.”

Among the building’s showpieces is a music recital hall, with a large window serving as an exceptional backdrop to the stage and providing the audience with south-facing views of the Toronto skyline. Above the hall will be a 400-seat event space with similar skyline views. There will also be a café on the ground floor and a multi-storey atrium leading up to the recital hall.

“Because the building is a large and complex site, the experience doesn’t just play out on the ground floor, it climbs through in a kind of spiral up until the performance space,” says Richard Sommer, dean of the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design and a member of the university’s Design Review Committee.

And the views will be just as impressive from the exterior of the building, says Delgado.

“The building is very engaging,” he says, adding that it will be particularly striking when driving or walking northbound along Queen’s Park Crescent.

Delgado says the building’s location will serve as a gateway that connects Toronto’s cultural corridor with the university. “It represents an important new addition to the cultural corridor with the Gardiner Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Faculty of Law and Queen’s Park.”

It’s important for the university to have public-facing buildings that sit on the borders of its downtown Toronto campus, says Sommer.

“The edges of the campus and its borders with the city are the places where you engage the community and the vibrancy of the city of Toronto,” he says. “When you have buildings that are at these edges, it’s particularly important that they have programming that produces a platform for public exchange.”

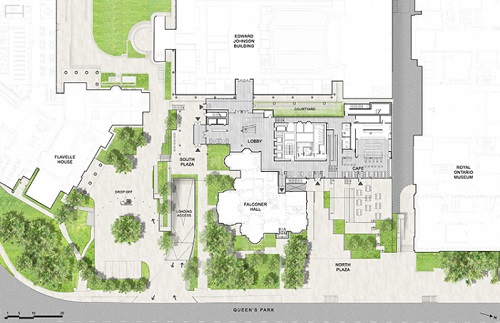

The building will also honour U of T’s history and heritage, carefully incorporating the 118-year-old Falconer Hall, part of the Faculty of Law, into its design.

“Falconer Hall provides an opportunity to integrate the old and the new in an exciting way,” says Delgado. “As opposed to an addition to an historic building, what we see here is a novel and creative way of having a historic building influence a new building.”

Charles Renfro, partner-in-charge at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, says the building is designed to encourage individual scholarship, while fostering collaborative discourse and public engagement.

“This ‘campus within a campus’ is revealed in the building’s dual identity – a smooth cohesive block of faculty offices and workspaces gives way to a variegated expression of individual departments as the building is sculpted around Falconer Hall, the historic home of the law department. Several public programs are revealed in the process. At the heart of the building is a dynamic central atrium and stairs linking all floors with clusters of lounge spaces, study spaces and meeting rooms, mixing the various populations of the building with each other and the general public,” he says.

As part of U of T’s commitment to sustainability, the building will adhere to the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers’ (ASHRAE) sustainability standards.

“It will use roughly 40 per cent less energy than a conventional building of this type,” Delgado says. “The dominant issue right now in terms of sustainability is minimizing the carbon footprint of our buildings and our facilities.”

The new U of T landmark will be built on the site of the McLaughlin Planetarium, which was closed in 1995. The university’s department of astronomy and astrophysics has included a state-of-the-art planetarium theatre in its plans for a proposed new building at 50 St. George St.