Considerations

Barriers to Experiential Learning

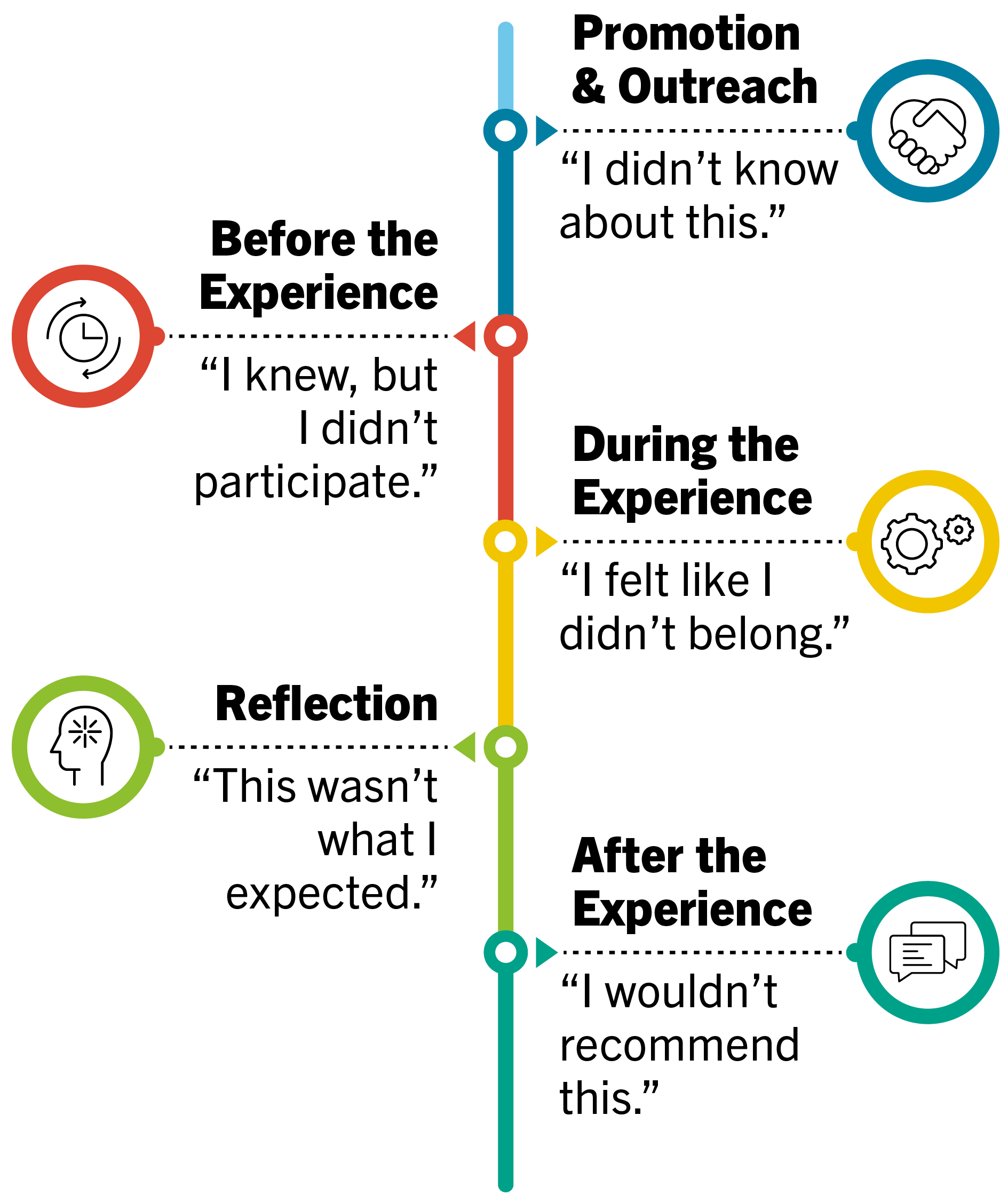

An example of the experiences and barriers that students may encounter when accessing EL programs.

An example of the experiences and barriers that students may encounter when accessing EL programs.

While participating in experiential learning (EL) can be beneficial and has been reported to improve student engagement, academic outcomes and personal development, there exist structural and systemic barriers that hinder students from accessing EL opportunities. For example, participation rates in EL are unevenly distributed, with underrepresentation among students who are Indigenous, Black and Racialized; international students; first-generation students; and students with disabilities (Stirling, 2019; Hora & Chen, 2020). It is imperative to address these barriers to student engagement in EL as they can further exacerbate existing inequities.

While some barriers to access might seem more apparent, students can face barriers across all stages of experiential learning, as represented in Figure 2. The barriers that students may face can result in being unaware of available opportunities, being or feeling unable to enrol in an opportunity, not feeling a sense of belonging and possibly opting out mid-way, skill development being hindered by negative experiences and discouraging others from participating, among other possibilities.

Promotion and Outreach: "I didn't know about this."

Before the Experience: "I knew, but didn't participate."

During the Experience: "I felt like I didn't belong."

Reflection: "This wasn't what I expected."

After the Experience: "I wouldn't recommend this."

Examples for Specific Student Populations

The following list provides some examples of barriers and inequities that equity-deserving students may face in relation to accessing or engaging in experiential learning opportunities. These examples are only intended to highlight potential challenges and we caution against making generalizations about students based on their identities.

While the following list provides examples for specific student populations, it is important to take an intersectional approach to understanding possible barriers that might be faced by students with different identities and lived experiences. In other words, students with intersecting identities (e.g., a racialized student with a disability) may contend with multiple barriers and their subsequent compounding impacts. For example, a student from a low-socioeconomic background who is part of the 2SLGBTQ+ community may not only face financial barriers when considering international EL opportunities but might also have limited options in terms of selecting EL experiences in countries that are welcoming and supportive of their intersecting identities.

International students

International students may face barriers that include visa regulation, limited access to networks, discrimination, and lack of recognition for skills and experience developed internationally (Jackson et al, 2017; Tran & Soejatminah, 2017; Wall, Tran & Soejatminah, 2017). These factors may hinder participation in valuable EL opportunities with compounding impacts. For example, international students in Canada within five years of graduation earn less than domestic peers with similar educational credentials, in part due to lower participation in work opportunities.

Indigenous, Black and Racialized students

Indigenous, Black and Racialized students may experience discrimination (such as subtle and overt racism) and harassment when engaging in experiential learning opportunities, and may opt out of enrolling in work-integrated learning courses because of these concerns. Also, they may not see themselves represented in the spaces they enter or may feel discouraged to participate if none of their peers are participating. Lake (2021) reported that Black students were discouraged from participating in EL if no other Black students were represented.

2SLGBTQ+ students

2SLGBTQ+ students can experience discrimination and/or a lack of belonging through curriculum, environments and processes that are not inclusive of diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, which can contribute to barriers when seeking employment. 2SLGBTQ+ students may also opt out of international experiences due to potentially hostile social and legal contexts in the host country.

Students from low socioeconomic backgrounds

Students from low socioeconomic backgrounds may face financial challenges (e.g., transit costs, purchasing relevant attire, student fees, access to technology and/or internet, etc.), and scheduling challenges due to employment or familial commitments (Cooper, Orrel & Bowden, 2010). Some may also have a lower cumulative grade point average (CGPA) due to having to dedicate significant energy to finance their education. EL opportunities with CGPA requirements may then pose an additional barrier to participation.

Students with disabilities

Students with disabilities may face misconceptions about perceived capabilities, feeling undervalued or devalued, discrimination, invisible barriers (e.g., anxiety) and physical and/or environmental barriers. For example, research shows that people with disabilities may have a lower employment rate and lower earnings than those without disabilities (McCloy & DeClou, 2013; Casebeer, Eger, & Water, 2017).

First-generation students

First-generation students can face challenges relating to lack of social capital (e.g., limited networks), familial pressures and lower levels of financial support (Katrevich & Aruguete, 2017). Additionally, first-generation students may not be as aware of possible experiential learning opportunities, and/or the added value that EL can bring to their student experience and degree, which can impact their overall engagement in EL.

It is essential we work to address these systemic and structural barriers to accessing and participating in experiential learning opportunities. We need to acknowledge and address biases in policies, processes, curriculum and programs that impact student engagement and experiences in EL. We hope that this five-stage framework will support you in mitigating potential barriers and increase equity, diversity, inclusion and access in your experiential learning opportunity.

Definitions

Establishing Shared Language & Understanding

In this guide, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Access (EDIA) is used to describe the process of enabling equitable access to opportunities and resources, ensuring that different needs and experiences are considered when designing, implementing and evaluating EL opportunities, and that those considering or participating in EL feel a sense of belonging. EDIA in EL involves the active dismantling of systemic, curricular and programmatic barriers that can limit or hinder participation for students.

It is important to establish shared language as we discuss EDIA in EL within the context of this guide. The following represent key terms and their definitions that will be referenced throughout this guide.

Experiential learning is an umbrella term that describes activities that purposefully integrate students’ academic study with direct real-world experience and focused reflection. The University of Toronto has categorized experiential learning into 10 unique types.

An instructor, faculty or staff member that is actively engaged in the design, development, delivery and/or evaluation of EL opportunities involving students.

Work-integrated learning is a sub-set of EL that integrates students’ academic experience within a practice or workplace setting and includes an engaged partnership between the academic institution, a host organization (e.g., employer, community partner) and a student (CEWIL, 2021). Due to the connection to the workplace, WIL opportunities may have additional considerations, such as those relating to hiring, that are not present in other forms of experiential learning.

For context, an equity-deserving group describes those who have been systemically excluded or are constrained by existing structures and practices. While definitions for equity-deserving groups may vary, for the purpose of this guide, we have decided to focus on student populations that may experience barriers when engaging in EL opportunities. Our definition of equity-deserving students therefore includes (but is not limited to) Indigenous, Black and Racialized students, students with disabilities, 2SLGBTQ+ students, international students, first-generation students, students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and students with caregiving responsibilities. The term equity-deserving aligns with University of Toronto Scarborough Principal Wisdom Tettey’s installation address on inspiring inclusive excellence.

An individual belongs to different social identities (e.g., race, gender, age, etc.), and these identities intersect and may impact an individual’s lived experience. This concept is known as intersectionality — a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw that speaks to the way that social identities are impacted by systems of power, resulting in compounding inequities. An intersectional approach provides a framework to contextualize how peoples’ social identities overlap (Ramos & Brassel, 2020) and centreing this approach can support EL practitioners in developing inclusive opportunities that take into consideration the various needs, capacities and experiences of students.

Maher and Tetreault (2001) as cited in Misawa, 2010 states positionality as being the idea that “people are defined not in terms of fixed identities, but by their [social] location within shifting networks of relationships, which can be analyzed and changed”. Positionality therefore refers to the relational nature of people's various social identities (e.g., ability, race, sexuality, etc.), and how these might shift and become more or less salient in the different environments they participate in. This can directly influence dynamics of power and privilege in different groups and settings.

Universal Design for Learning promotes inclusive practices that aim to increase accessibility and optimize the learning environment for all. It is a curriculum design, development and delivery framework that enables multiple means of engagement, representation, action and expression in teaching and learning (CAST, 2018). For EL practitioners, this can be achieved in a variety of ways, including considering how students will interact with the learning materials, utilize relevant technology, engage with partner organizations and more.