Findings offer opportunities for improved smell tests in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

Neurobiologists at the University of Toronto have identified a mechanism that allows the brain to recreate vivid sensory experiences from memory, shedding light on how sensory-rich memories are created and stored in our brains.

Using smell as a model, the findings offer a novel perspective on how the senses are represented in memory, and could explain why the loss of the ability to smell has become recognized as an early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Our findings demonstrate for the first time how smells we’ve encountered in our lives are recreated in memory,” said Afif Aqrabawi, a PhD candidate in the Department of Cell & Systems Biology in the Faculty of Arts & Science at U of T, and lead author of a study published this month in Nature Communications.

“In other words, we’ve discovered how you are able to remember the smell of your grandma’s apple pie when walking into her kitchen.”

There is a strong connection between memory and olfaction – the process of smelling and recognizing odours – owing to their common evolutionary history. Examining this connection in mice, Aqrabawi and graduate supervisor Professor Junchul Kim in the Department of Psychology at U of T found that information about space and time integrate within a region of the brain important for the sense of smell – yet poorly understood – known as the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON).

“When these elements combine, a what-when-where memory is formed,” said Aqrabawi. This is why, for example, you might have the ability to remember the smell of a lover’s perfume (the what) when you reminisce about your first kiss (the when and where).

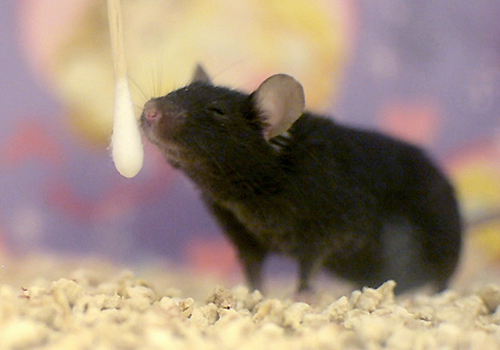

Curious about the function of the anterior olfactory nucleus, Aqrabawi and Kim designed a series of tests to exploit the preference of mice to sniff new odours.

“They prefer to spend more time smelling a new odour than one that’s familiar to them,” said Aqrabawi. “When they lose this preference, it’s implied they no longer remember the smell even though they have sniffed it before, so they continue to smell something as if for the first time.”

In the course of examining the structure and function of the AON, the researchers uncovered a previously unknown neural pathway between it and the hippocampus – a structure critical for memory and contextual representation, and highly implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. They found they could mimic the odour memory problems seen in Alzheimer’s patients by disconnecting communication between the hippocampus and the AON.

Whereas the mice whose hippocampus-AON connection was left intact refrained from returning to familiar locations to sniff odours that were no longer novel, those with a disconnected pathway returned to sniff previously smelled odours for longer periods of time. Replicating early degeneration of the AON demonstrated the inability of the when-where context to complete the function and provide the what of the odor memory.

“It demonstrates that we now understand which circuits in the brain govern the episodic memory for smell. The circuit can now be used as a model to study fundamental aspects of human episodic memory and the odour memory deficits seen in neurodegenerative conditions,” said Aqrabawi.

There is a vast body of work that reports olfactory dysfunction – particularly olfactory memory loss – as symptoms of the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Such deficits in the ability to recognize odours precede the cognitive decline and are correlated with the degree of illness.

The AON has a well-documented involvement in Alzheimer’s disease but not much else is known about its function. It has consistently been reported to be among the earliest sites of neurodegeneration including the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, which are abnormal proteins found in Alzheimer’s patients.

Because of this, smell tests are now used in the hopes of detecting the early onset of Alzheimer’s, yet they are imperfectly designed since the underlying cause of the olfactory problems remain unknown.

“Given the early degeneration of the AON in Alzheimer’s disease, our study suggests that the odor deficits experienced by patients involve difficulties remembering the ‘when’ and ‘where’ odours were encountered,” said Kim.

The researchers say that with a better understanding of the neural circuits underlying odour memory, tests that directly and effectively examine the proper functioning of these circuits can be developed.

“Such tests might be more sensitive to detecting problems than if patients were prompted to remember an odour itself,” added Kim. “The motivation to develop them is high due to their quick, cheap, and easy administration.”

The findings are described in the study “Hippocampal projections to the anterior olfactory nucleus differentially convey spatiotemporal information during episodic odour memory”, published this month in Nature Communications. Support for the research was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.