Tucked away on the lower level of the University College building are two tiny rooms, filled floor-to-ceiling with archive-quality banker boxes containing one of the University of Toronto’s most unusual collections.

This is U of T’s Sexual Representation Collection, a comprehensive archive of modern sexuality belonging to the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies in the Faculty of Arts & Science.

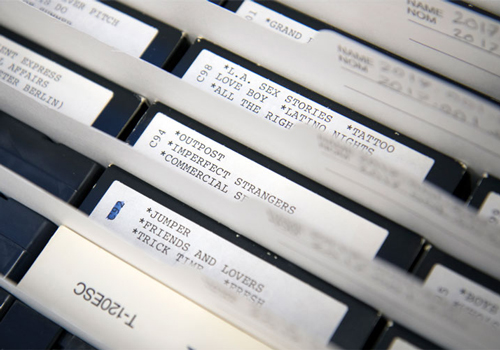

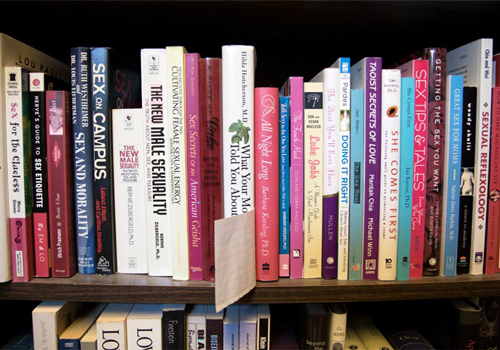

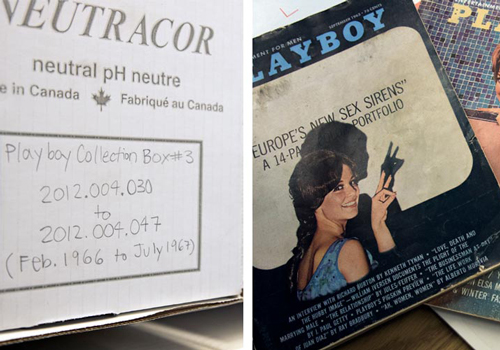

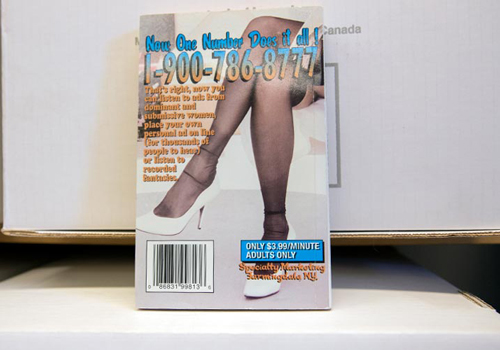

The boxes contain everything from pornographic VHS tapes, erotic novels and Playboy magazines to documents related to legal battles around censorship – all acquired by previous collection directors and donated by a variety of benefactors including a sex shop in Scarborough, a former CBC producer and prominent sex educators.

The collection serves as a historical record of the shifts in how sexuality is viewed and understood, says Patrick Keilty, the collection’s archives director and an assistant professor in the Faculty of Information and sexual diversity studies.

“It tells us about the limits of our society, of what’s acceptable, and it tells us about certain kinds of contexts of production and consumption,” he says.

In the 1990s Brian Pronger, an associate professor in what was then the Faculty of Physical Education and Health, began growing the collection with the help of Mariana Valverde, a professor at the Centre for Criminology & Sociolegal Studiesand one of the founders of sexual diversity studies at U of T. Valverde worked with Pronger to secure funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) to build the Sexual Representation Collection.

The ’90s saw culture wars that divided feminists around issues of pornography and sexual identity, and the rise of the internet, which changed the way people consumed pornographic content.

“Brian started to think it was really important to start archiving the kinds of things that were beginning to happen in the early days of easy internet access,” says Valverde.

Pronger’s collection was, no doubt, controversial at the time, but decades later, researchers are recognizing the value of this kind of archival material.

“A lot of these things are invaluable in a sense that nobody has copies of it because at the time there might have been a lot of copies of certain kinds of videos or magazines but it’s not the type of stuff people would keep for the long run,” Valverde says.

The Sexual Representation Collection also highlights the ways the porn industry was ahead of the curve, adopting new technology and business models that soon after became mainstream, says Keilty.

“It was the porn industry that embraced VHS and made it ubiquitous because Sony wouldn’t let them use Betamax so they were forced to use VHS, and they started up what became video rentals,” he says.

The influence mainstream media and the porn industry had on each other is an important story to tell, says Keilty.

“Everything from 3G mobile technology to BluRay to VHS to secure credit card processing all originates or was heavily promoted by the porn industry,” he says.

The archives are available to researchers studying various aspects of sexuality inside and outside the university and are incorporated into class curricula. This coming year, several classes will be using the archives for research projects, says Keilty.

Students in a history course called Hacking History will be creating a digital exhibition of the Max Allen collection – an archive of materials donated by the CBC producer that includes documents relating to his legal battles around obscenity laws from the 1970s to the ’90s.

Keilty will be running a workshop out of the Faculty of Information about how to tell the story of “smutty” archives and archival objects.

“Archives always have the challenge of bringing to life their materials beyond just exhibiting it in an exhibit case,” he says. “They have to make sure it’s not merely information but that it’s also sexual and has a life and a history and to convey all the different sociopolitical contexts around these objects.”