Two books had a profound impact on Paul Stevens’s life — one led him to the army, the other to university.

His love of the second book, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, has most recently led the chair of the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of English to be named the Honored Scholar of the Milton Society of America for 2022.

He is the fourth honoured scholar from the department at the University of Toronto. The others were the late Arthur Barker (1973), a former head of English at Trinity College and a pioneer in understanding Milton’s politics, the late Northrop Frye (1975), one of the 20th century’s pre-eminent scholars and literary critics, and more recently, Mary Nyquist (2011), a towering authority on the interconnections between liberalism, transatlantic slavery and political servitude. Seeing this list takes Stevens back to his days as a graduate student and being a TA for Frye’s course on religion in the 1980s.

“Wonderful as Frye was (and he was), the Milton tradition at Toronto was never just about repeating Frye; it went back way earlier and was always about creating something new,” says Stevens, who was delighted to receive the honour.

“I'm just finishing a five-year term as chair and my mind is entirely caught up in administration,” he says, noting that running a department as large and complex as English during COVID has been challenging.

“The award was surprising in the sense that it's not remotely connected to what I’ve been thinking about. To get this honour suddenly coming out of the blue has been especially gratifying.”

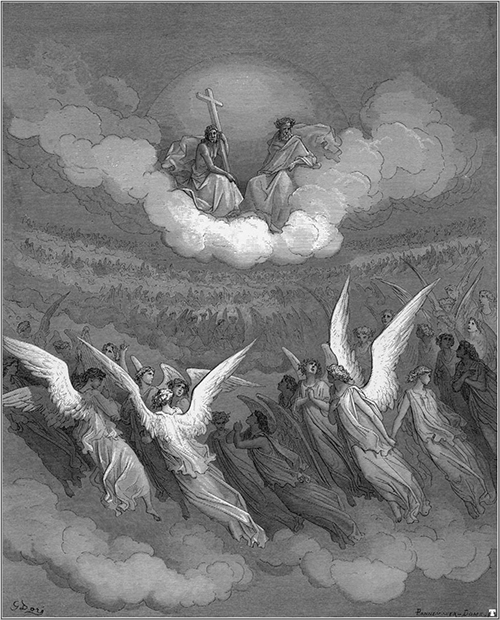

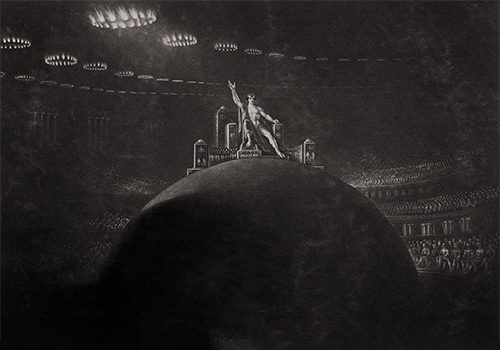

Stevens first cracked open Paradise Lost — Milton’s epic biblical 11,000-line poem about the fall of man — when he was a schoolboy in Wales.

“I'd never read anything like it, I couldn't stop reading it,” he says. “It was fantastic, relentless, joyous. The verse drove you forward and I couldn't put it down. I was also, like many other boys at that time, reading a lot of military history but there was nothing quite like this stuff.”

That military history included the works of novelist and poet Robert Graves, including a novel titled Proceed, Sergeant Lamb about the life of Roger Lamb, a young working-class soldier who served with the Royal Welch Fusiliers during the American War of Independence (1775-1783).

The book was a kind of “male cinderella” story and it inspired the adolescent Stevens to join the British Army. Like Graves’s character, Stevens served as a soldier in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, joining the UN peacekeeping force in Cyprus, and then later as an officer in the Royal Regiment of Wales serving in Gibraltar, Belize, Northern Ireland during “the Troubles,” and finally Berlin. But in all that time he never forgot Milton.

Returning to academia, Stevens pursued teaching and research in Milton and other 17th-century writers. His first book, Imagination and the Presence of Shakespeare in “Paradise Lost” examined the way Shakespeare appears to function in Milton’s mind as a metonym for the imagination at its most fertile, life-giving. But he feels he made his mark with series of more political articles which showed how Paradise Lost, even while authorizing the West’s colonial imperative, simultaneously undermined it.

An award-winning teaching and research career followed that included several books and dozens of influential papers and essays on Milton. He is also the founder and coordinator of the annual international Canada Milton Seminar which will soon be taken over by the department’s new Canada Research Chair, John Rogers.

Surprisingly, Graves and Milton do intersect — though not in the most flattering way.

“Graves hated Milton, absolutely hated him,” says Stevens. “Graves actually wrote a great novel called Wife to Mr. Milton which is the story of Milton's life as seen from his wife's perspective. The two poets are deeply interrelated and the monster Graves produces through Mary Powell’s eyes suggests the intensity of his struggle as a poet with Milton’s overwhelming force.”

Continuing to teach Milton, Stevens sees the poet’s power and impact on students today as immeasurably enabling.

“I've never taught a course on Milton where I haven't had students going gaga,” he says. “And that’s not me. That's the poet. That's the power of the literature. All the teacher is doing is pointing and showing the way.”

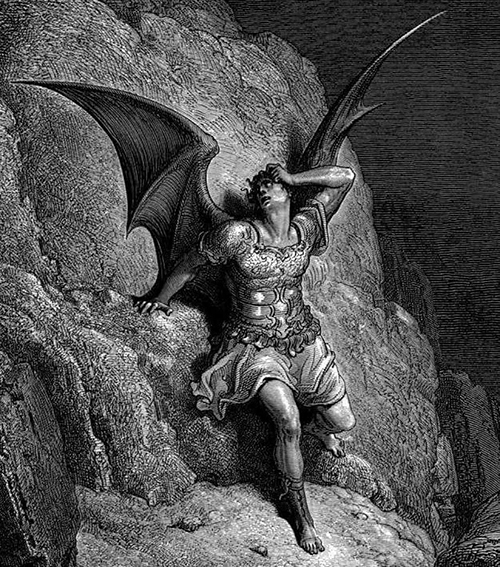

One former student, Erin Shields, who graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in 2008 as a member of University College, took Stevens’s course on Milton and was deeply influenced. She became an award-winning dramatist who created a modern, feminist retelling of Milton’s epic poem with Satan as a woman that was featured at the Stratford Festival in 2018.

“I found Erin’s feminist re-creation deeply moving,” says Stevens. “That's the kind of thing that makes you realize why teaching and especially teaching Milton can be exhilarating.”

And it’s not just students who are moved by Paradise Lost — for Stevens, the discoveries and new ideas emerging from this poem seem never-ending.

So for undergraduate students, Stevens has a message — Milton is not obsolete.

“There’s an enormously popular, long-standing idea of Milton as Graves’s monster — stern, forbidding, life-denying” says Stevens. “And, yes, he was a powerful figure, but his vision of human life and all the possibilities of human life is sublime — it is liberating for anyone regardless of who they are or where they come from. In Paradise Lost, even as he reproduces the West’s formidable grand narrative, for instance, he allows us to see the danger of all totalizing arguments, compelling as they might seem at the moment. In that, his art sets us free.”