The current cohort of undergraduate students has entered adulthood in a stark new reality: they’re surrounded by an abundance of information and digital tools that shape much of their experiences of the world. The importance of thinking about personal data and navigating the complexities of sophisticated technological systems is an integral part of this generation’s — and everyone’s — digital literacy.

As they navigate this landscape, some students in the Faculty of Arts & Science had the distinct advantage of guidance from Irene Poetranto, PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science and senior researcher for the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy.

In the fall of 2023, Poetranto taught Digital Technologies and Human Rights (MUN198H1), a course examining the technologies powering everything from facial recognition software to home appliances to social media. The course encouraged students to consider how we might govern and use these technologies to mitigate harm — areas of focus for the Schwartz Reisman Institute’s (SRI) policy and research teams as well.

As part of their thinking about these issues, some students in the course attended the book launch for SRI researcher Wendy H. Wong’s We, The Data: Human Rights in the Digital Age (MIT Press, 2023).

Co-hosted by SRI and the Munk School, the book launch featured an on-stage conversation between Wong, professor and principal’s research chair at the University of British Columbia Okanagan’s Department of Economics, Philosophy, and Political Science, and Anna Su, an SRI research lead and an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto.

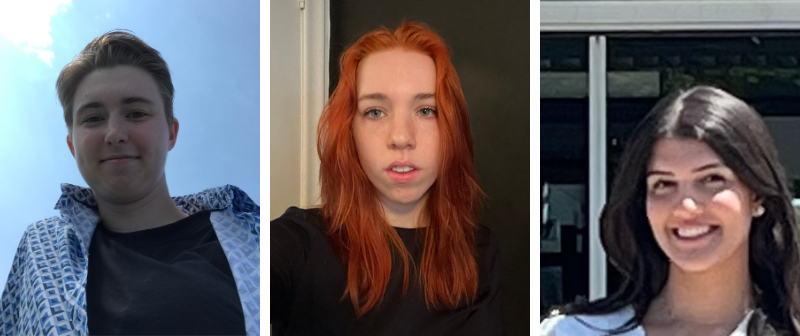

Below, some of Poetranto’s students share their reflections on the conversation between Wong and Su — and the pervasive role that data plays in their lives.

Undergraduate student Imogen Bechan-Revis says the book launch was “an eye-opening event.”

“The details surrounding who has access to our data and where it is stored are not divulged to the public,” says Bechan-Revis, pointing to this lack of transparency as a potential violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and its four pillars of dignity, liberty, equality, and autonomy.

“23andMe is a perfect example,” says Bechan-Revis, referring to the popular genetic-testing tool. “It illustrates how our privacy is infringed upon when companies store our personal information, at times without our knowledge. It’s unclear what happens with DNA after testing, and the risk of a data breach means it could be sold on the black market. Currently, there are no laws or regulations that would hold these companies accountable if this were to happen.”

The book launch discussion also raised “an interesting point about the future use of data,” says Bechan-Revis. “Professor Wong explained the potential to digitally recreate a person even after they died by using their data. This could result in numerous issues surrounding consent, ethics, and the UDHR — not to mention widening the digital and social divides.”

“Professor Wong really masterfully communicated both the importance and the dangers of the digital age to her audience,” says Bechan-Revis. “She especially highlighted the importance of being data literate so we can reduce our digital footprint.”

First-year humanities student Lola Bjork Zegers also found the notion of recreating a person after their death to be the most compelling discussion point.

“One’s data can live on after their death,” says Zegers, explaining the concept of 'digital immortality' developed in Wong’s book.

“This data could be used to ‘recreate’ a person by having AI mimic their characteristics, patterns of behaviour, and general way of being. This raises an important human rights question: does using people’s data as a commodity violate their right to dignity? Liberty? A human right which has not yet been created?”

“This last idea was one which Professor Wong expanded upon, stating that new human rights must be created in order to generate debate and discussion on what is or isn’t acceptable,” says Zegers.

“We — the users — need to do more to protect ourselves,” says Zegers. “Professor Wong points out that we need to think of ourselves as data ‘stakeholders’ who remain informed of the implications that decisions about data and technology may have on us and our future. We need to make decisions as though we have a say in what happens with our data — because we do. And in order to ensure the universal ability to make informed decisions, Professor Wong asserts that we need to have something like a right to data literacy. This requires resources like public libraries, computer access, and public outreach programs to help advance data literacy for everyone.”

We need to make decisions as though we have a say in what happens with our data—because we do. — Lola Bjork Zegers

First-year student Elise Corbin, an international student from the U.S., says hearing Wong speak “was a refreshing experience for me, a computer science major used to the doctrine of techno-determinism.”

“Professor Wong presented a compelling case for stepping back and considering what values and ideas AI and other digital technologies reflect,” says Corbin. “In Professor Poetranto’s course, we had weekly discussions about who should regulate the creation and implementation of new technology, as well as whether certain new technologies are worth being implemented at all.

“This is a perspective that few computer science students are exposed to in our undergraduate careers,” says Corbin — although SRI and the Department of Computer Science in the Faculty of Arts & Science are attempting to change that through the Embedded Ethics Education Initiative (E3I).

In fact, Corbin agrees that the mission of E3I is crucial: “Perhaps if all undergraduate computer science students took at least one ethics course before graduating,” she says, “we would bring a more human-centered approach to our careers. Data literacy is important, but I also believe that the reverse is equally true. People with expertise in data and programming should learn to think about whether the technologies they create are really helping people.”

Undergraduate student Diana Zhao says the book launch discussion exposed her to “the true potency of our data,” again remarking on data’s use after our deaths — a compelling point that caught the majority of attendees’ attention.

“Previously, my knowledge of data was limited to its significance in our present era: our dependence on it, its integration into our day-to-day functions, and the holistic composition of our digital presences,” says Zhao.

“But I had never considered data’s applicability to our lives in the future. Professor Wong presented a facet of data that she calls ‘stickiness,’ referring to data’s permanence and omnipresence. I realized that even after our deaths, data remains immortal. So, everything that’s collected about us —ranging from our tastes and preferences to our personal information — is controlled by companies who monetize and exchange this data for their own intents.

“What, then, is the significance of our current selves, if we are so easily replicated with the imprints we leave online?” asks Zhao. “Thinking about this kind of data exploitation during the book launch was both fascinating and unnerving.”

Undergraduate student Thishan Sivaneswaran says it was his first time at an event like this one, “and it was a big learning experience.”

“What happens to data after we die? This is something that I had briefly thought about before but never in much depth,” says Sivaneswaran. “It really shifted the way that I thought about the uses of data. I thought creating ‘digital doubles’ was something that only happened in movies — but it’s clear to me now that it’s no longer fiction but a possible reality.”

Sivaneswaran expressed concerns about what this means for the future of humanity.

“What if the rich utilize their resources to carry on living for as long as possible through data? Will this result in the creation of a sort of ‘untouchable’ class of digital humans with the ability to do almost anything? I hope that humanity finds a balance between the development of data-intensive technology and the availability of this technology to the public,” says Sivaneswaran. “The general population needs to see increased rates of data literacy for these kinds of powerful technologies to be useful for everyone and for the betterment of society.”

“One of the biggest things I learned about through Professor Poetranto’s course and the book launch event is the concept of the digital divide,” says Sivaneswaran. “The issue of low data literacy is deeply related to the digital divide: both are barriers to succeeding in the modern world and keeping up with new technologies. I think that working on either one of these issues helps solve the other. With more access to the internet and other digital resources, data literacy will increase and vice-versa.”

I hope that humanity finds a balance between the development of data-intensive technology and the availability of this technology to the public. — Thishan Sivaneswaran

Finally, first-year undergraduate student Sanam Singh — who aims to double major in the ethics, society & law program at U of T’s Trinity College and the peace, conflict & justice studies program at the Munk School — reflected on the concept of “datafication,” and its implications for human rights.

“The concept of ‘datafication' reminds us that data is not just about us individually: it is eternally sticky, interconnected, and intertwined with so many aspects of our — and others’ — lives,” says Singh.

“I’m curious about and interested in the legal system — both nationally and internationally. So, the conversation around how ‘datafication’ is fundamentally altering the way human rights are protected deeply resonated with me,” says Singh.

Like others, Singh says she found the idea of digital recreation after death to be “both disturbing and thought-provoking. There is an urgent need to question the legal, moral, and ethical perspectives of recreating individuals digitally after their death,” says Singh. “The mismatch between the challenges posed by datafication and existing regulatory frameworks has emphasized the need for us as global citizens to advocate for a universal framework to preserve human potential and protect human rights.”

The Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society thanks Irene Poetranto and the students quoted in this piece for their time and effort in attending the book launch event and sharing their reflections on the crucial role of human rights in an increasingly data-centric world.