When Ian Williams was in grade six, a teacher told him that he shouldn’t attempt to play the French horn because the mouthpiece was too small for him. He understood that to mean that his lips were too big for the horn.

Though just 11 years old, he vividly remembers the feeling of unease, a new uncomfortable awareness that by being Black he was somehow different from his classmates.

“That sticks,” says Williams. “If you constantly learn about your race in these negative kinds of context, you're constantly off balance for the rest of your life, always pointing back to that experience.”

It’s one of the first of countless incidents where Williams was subjected to racism — often coming in the form of a small comment, gesture or even a look. Every one of these events, that continue to this day, impacts how he moves through life, taking up valuable mental and emotional space.

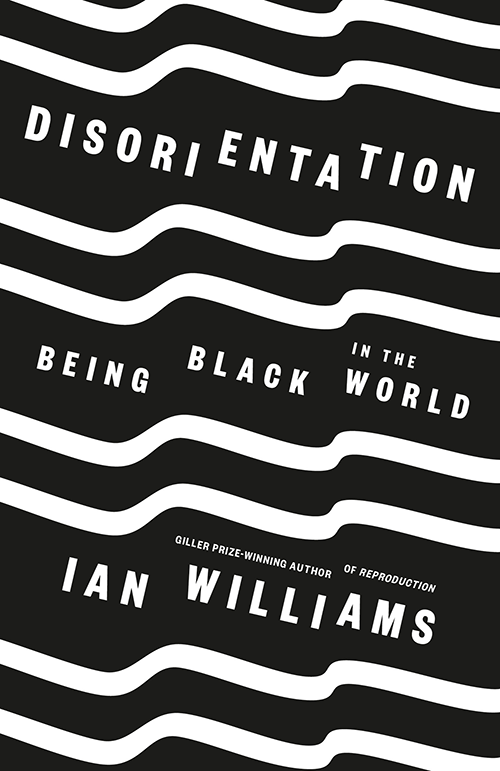

Williams, an awarding-winning novelist and poet, and an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of English has captured how these experiences have shaped his life and his state of mind in his most recent book, Disorientation: Being Black in the World.

This essay collection was shortlisted for the Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Nonfiction with the winner being announced November 3, 2021 with a $60,000 prize.

Some of the book’s essays are analytical and theoretical like the ten characteristics of institutional whiteness; and blame culture — or how do we make tangible change when no one feels responsible for the systemic structures of the past.

But most are personal essays that chart Williams’s course through the world and the different receptions to his body and his presence.

“I suggest that when Black folk recognize or are informed that they're Black, it's a profoundly disorienting experience,” says Williams, who previously won the 2019 Scotiabank Giller prize for his novel Reproduction.

Disorientation was born out of a difficult 2020 summer that included massive wildfires around Vancouver, where Williams was living at the time, a steady stream of racial violence and justice movements happening south of the border, and the global COVID-19 pandemic.

“All of these things happening in the world, it felt apocalyptic,” he says.

What does race and racism look like in a middle-class suburban landscape with no bullets flying, without chokeholds? What are the tiny indignities that Black people face that multiply and accrue over time in Canada? If we can identify them, maybe we can start to address them.

Amid this steady barrage of bad news, Williams felt compelled to share his experiences of being Black. As well, with so much attention being paid to racial tensions in the United States, Williams wanted to offer his perspective on racism in Canada.

“All of this media about killings, shootings, the ‘Karen's’, all of this analysis was coming up from America,” he says. “As Canadians, we tend to not centre the discussion on the Canadian landscape.

“What does race and racism look like in a middle-class suburban landscape with no bullets flying, without chokeholds? What are the tiny indignities that Black people face that multiply and accrue over time in Canada? If we can identify them, maybe we can start to address them.”

These smaller scale incidents never make the news, but they’re no less damaging and impactful, believes Williams who can recall hurtful events from every chapter of his life.

“Like walking into the department store at 16 and having the attendant look at you suspiciously because of who you are,” he says. “And this happens in elevators, in hallways, it happens all over the place.”

What’s not visible is the constant mental assessing and processing of situations — a never-ending analysis of the environment.

“You're always receiving information about whether you're welcome or not,” says Williams. He’s asked himself, ‘Can I actually stay in this coffee shop today? Because last week, I couldn't.’

“There all of these tiny negotiations that constantly happen. And it's never just a single event. It’s all of the history that we carry with us from these constantly disorienting moments. Every time one of them happens, we get slapped in the face.”

And it’s not like such incidents have stopped in his everyday life.

So many of my Black friends are exhausted in a way that’s not linked to their jobs or anything. It's just linked to like being Black in the world and trying to understand and shield themselves and their loved ones from these constant impositions. If this happened to you on a weekly basis, it would wear you down

“A few days ago, I’m playing tennis in Vancouver,” says Williams. “And the people on the next court only addressed my white tennis partner.”

Several times, when their ball rolled onto the adjacent court, Williams held up his racket and waved, asking politely for the ball back. They acted like he didn’t exist.

“Now you can say, no big deal, right? And in that moment, it would be hard for me to prove that that is a particularly racist occurrence. It’s those kinds of things that we don't want to talk about as racist activity because they’re so tiny, but that’s what racism looks like in Canada.”

And the mental effort it takes to recover from these constant reminders of one's race is taxing, says Williams. “While other people move from interaction to interaction, we have to do this processing and figuring out what went wrong.

“So many of my Black friends are exhausted in a way that’s not linked to their jobs or anything. It's just linked to like being Black in the world and trying to understand and shield themselves and their loved ones from these constant impositions. If this happened to you on a weekly basis, it would wear you down.”

Despite the obvious challenges and injustices, Williams insists Disorientation is not about laying blame or pointing fingers.

“I want to create a conversational space for us to talk about race in Canada in ways that are not punitive or didactic, but just open, transparent and sincere,” he says. “I'm not the race guru, I'm not the expert on Blackness. I just want to bring our racial experiences forward and have readers understand what we're doing to each other and what systemic things are doing to all of us.”

And to achieve this, he felt nonfiction was the right choice.

“I wanted to address the reader directly without the artifice of fiction, I wanted to talk directly to somebody in their living room,” he says.

“There are many ways I could talk about race, I can code it into a character, I can create hypothetical situations, create poetry. And I've done that. But just for a moment in my career, I wanted to pause with the imaginative and just deal with the real.”