Wondering if monogamy was more popular than polygamy in the 19th and 20th centuries? Curious to know which societies are linked to a common ancestor on a language tree? Well, a University of Toronto researcher and her colleagues have “D-PLACE” for you.

An open-access database, D-PLACE pulls together a searchable mass of information on the languages, cultures, locations and environments of more than 1,400 largely pre-industrial societies, as documented by ethnographers in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Anyone can use it for free, it has an easy-to-use interface, and it provides a quick view of how diverse humans really are,” says Kathryn Kirby, a postdoctoral fellow with U of T’s departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (EEB) and Geography.

Kirby was the lead author of a study by an international team of researchers that established the D-PLACE website. Their paper was published this month in the PLOS ONE journal.

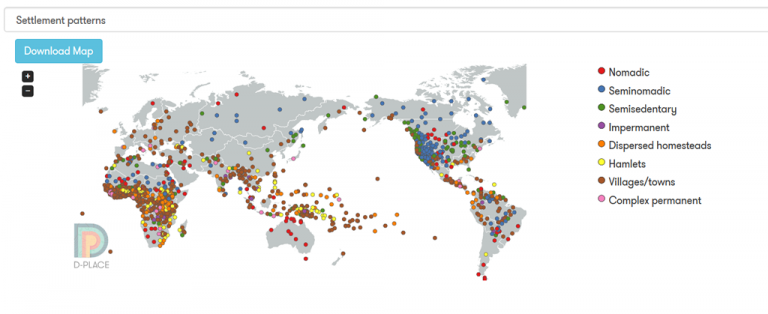

Visitors to the site can choose to display the results of their search in a table, map or a linguistic tree diagram, and even download the results for further analysis.

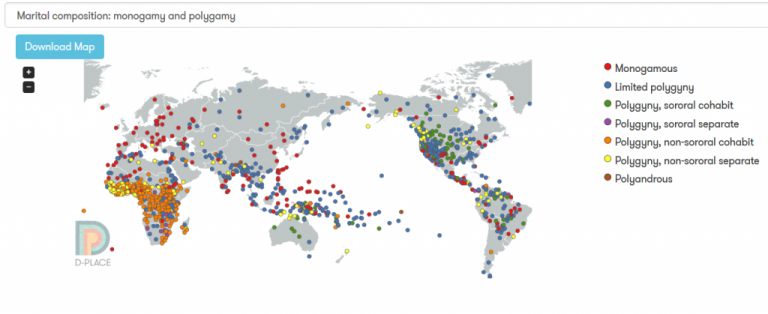

“For instance, you could ask which societies in the world are monogamous versus polygamous, and this would give you a snapshot of that pattern for a sample of 1200 societies from around the world,” says Kirby.

“To be able to look at the marriage systems for all those societies at a glance is pretty cool.”

D-PLACE shows family relationships, dependence on fishing, hunting and agriculture

By the same token, a website user could easily determine the pattern of so-called “nuclear” versus extended-family relationships for the same period, or explore societies’ relative dependence on fishing, hunting, and agriculture for subsistence.

The database largely depends on two previously published collections of cross-cultural data. Kirby and the other researchers tagged all the data available with specifics about the time and place where the cultural data was collected, then added information about the environmental conditions and ecosystems where each of the societies was located.

They also took advantage of new methods in linguistics to plot the history of those societies based on language, allowing users to see when societies diverged from a common ancestor.

“The cultural data is based on data points from 1800s and 1900s, but there are relationships that are represented in these linguistic trees that go back 10,000 years in some cases,” says Kirby.

“There are about 7,000 languages in the world, and we’ve got a snapshot of about 1,300 in the database, so there is this incredible diversity, and we’ve only scratched the surface of it.”

In the near future, D-PLACE will be updated to make its information more expansive, says Kirby, but the database is already a major step forward among the research tools available to scientists and academics.

Enabling a new generation to tackle questions about the forces shaping cultural diversity

While it’s easy for the public to use, it also maintains the original authors’ codes and ethnographic references for more sophisticated research. By doing so, D-PLACE may enable a new generation of scholars to tackle long-standing questions about the forces that have shaped the history of cultural diversity.

By combining linguistic, anthropological and ecological data, it also serves as an example of the type of interdisciplinary research that an increasing number of educators and academics say is the best approach for modern scholars.

“All the things you need to run a vigorous analysis of the drivers of cultural change are all in one place on this website,” says Kirby.

“And from a public perspective, it is just pretty neat to be able to see the relationships that are out there, because while the world is fabulously diverse in terms of cultural practices, basically, we’re all related.”